By Moé Yonamine

“I don’t understand why people talk about him like he’s a criminal. He was a 17 year-old kid,” Kiana said. Kiana was one of more than 100 students in my Mock Trial classes at Roosevelt High School in Portland, Oregon. As the most diverse high school in the state, our students brought in stories and connections to the criminal justice system that could not—and should not— be ignored in critically analyzing the justice system.

Many of my students have expressed feeling excluded by the legal and criminal justice system in talking about what is truly “just.” From the first day of class, students made it known that they were hungry for the real education—one that was relevant to their lives, that empowered them with learning about fighters who looked like them, and that gave them tools to change systemic injustices that they have seen in their own lives. Learning about Trayvon Martin was an important example.

Many students who are now juniors and seniors, brought up Trayvon Martin’s name when offering examples of injustice in the criminal justice system. Even some of the youngest 9th-grade students could recall where they were as middle schoolers when they learned about George Zimmerman’s not-guilty verdict.

Students could see themselves in Trayvon or in someone they care about. The heartbreaking question that continued to surface was: If this can happen to Trayvon, what does it say about society’s love and value of our lives? We read, we wrote, and we shared about each other’s stories of a time they or someone they know or watched experienced racial injustice. Several students gave recent examples of being stopped or harassed as they wore their hoodie. Dave, a white freshman student chimed in compassionately, “But it’s not like everyone gets stopped,” he said. “I could probably walk around with a hoodie on all day long wherever I go and not get harassed. It’s just wrong.”

Through these first months of school, we continued to hear on the news about Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, and Tamir Rice. We watched Usher’s new music video, “Chains” and Janelle Monae and Wondaland’s recent performance in Portland of their song, “Hell You Talmabout,” that sings through a painful list of unarmed African Americans who have been killed nationally, and in the Portland area.

“Why don’t we know about any of these people?” asked Reanna. “What can we do? I just want to cry.” Over winter break, many watched the news, and learned that the police officers who shot and killed Tamir Rice would not face trial. At the chime of the bell to begin class on the first day back, Myia began, “I could not wait to come back to school and talk about this. What was so reasonable about shooting a 12-year-old kid?”

As a teacher, I want to create a community where students can feel embraced in their sense of justice and injustice, to be able to imagine a more just world, and to learn how to be agents in making change. We had to learn how to organize for action and it needed to start in our own neighborhood. I encouraged students to go back to the questions that we started the year with as we began to educate ourselves on the criminal justice system and the prison system: What is the problem? What is the solution? Whose voices are included? Whose voices are missing?

Our Mock Trial classes watched a speech by Trayvon’s mother, Sybrina Fulton, who spoke at Maranatha Church in Portland last April asking the community to remember her son on his birthday with a special message to youth to be a part of taking action to creating a more just community. The students quickly reflected that their voices as youth from their North Portland neighborhood were missing. Our neighborhood is comprised of immigrants and refugee peoples with historically underrepresented African American and Latino groups, as well as low-income white families. Students were inspired to target February 5th, Trayvon Martin’s birthday, as a day of action to address systemic racism and racial profiling.

The students busily designed not just one project, but six projects leading to their day of action: creating fliers calling on a school-wide wearing of hoods, drafting letters to teachers and administrators, developing a student survey to ask about peer experiences, reaching out to the media about the day of action, and organizing a panel of prominent fighters from the African American community. Students in my three classes composed this letter:

Dear Teachers,

When we learned about Trayvon Martin, a lot of us were very impacted by his story. He was 17 years old from Miami. He, like us, had many dreams; one of which was to attend the University of Miami to study aviation and become a pilot. He was known for wearing his hoodie all year round even on the hottest summer days and was wearing a hoodie on his last day. What got to us also was the way that he was described in the trial and in a lot of the media as if he was “suspicious” or bad because he, as a young Black man, walked around wearing a hoodie. This is something that many of us can relate with and we want it to stop.

We put on a trial back in the fall and learned a lot about what happened on that last day. We also have been paying attention to reactions from around the country and learned about how “Black Lives Matter” began as a response by one of the founders in hearing about the verdict of George Zimmerman. Even since that verdict, we still keep hearing stories like Trayvon’s and we want to take a stand… We ask you, our teachers, to stand with us by wearing your hood. We also ask you to support your students in keeping their hoods on during class. It is a silent statement but a loud statement we hope to make together. He could have been someone we know or someone we care about.

Having our school united on this day with our hoods up will send a message that Black Lives Matter and our lives matter here. Our school may be the first one to have a school-wide Hoodies-Up Day in Portland and can lead our community by making this an annual reminder. We hope to inspire our neighborhood to take action by taking this stand against racism and racial profiling. If there is one thing we have taken away from this organizing for this day, it is that we will be active participators in making history and not passive bystanders watching it all happen.

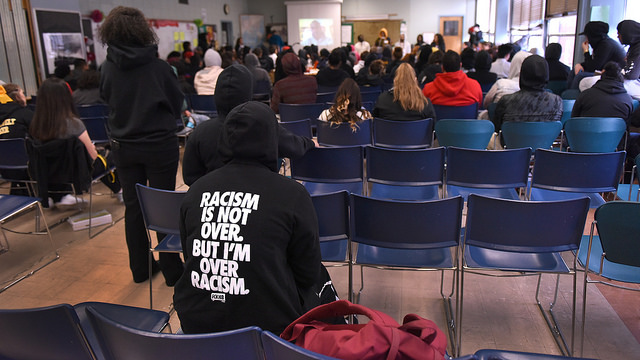

Their statement was read over the intercom the morning of the Hoodies-Up day this past Friday. As students and staff flooded the halls in hoods, students boldly sought solidarity in their stand to end systemic racism and racial profiling.

In the afternoon, the students were met with a dynamic presentation on “Justice Is…” by educators, activists and community organizers: Julian Hipkins of Washington, DC’s Teaching for Change (via skype), Nyanga Uuka and Llondyn Elliott of the Portland Urban League, Kayse Jama of the Center for Intercultural Organizing, CJ Robbins of the City of Portland’s Office of Equity and Human Rights and Black Male Advancement, and Renée Mitchell, a prominent slam poet of Spit/WRITE who teaches journalism and storytelling at Roosevelt. Panelists spoke passionately about their own experiences with racial injustice, sharing stories of taking action individually and collectively, while commending this day of action and students’ courage.

As more than 120 students leaned in hungry to take in the panelists’ every word, a sophomore student of mine, Miley, leaned over to me and said, “This is just the beginning.” She smiled proudly, adding: “We’re never going to forget this day.”

To the media, the students had a strong message. “A hoodie doesn’t define me,” said TJ, signaling his resistance to the prejudice and discrimination he sees around him. “Know the person under the hood,” echoed Carter, demanding the world to see the humanity in the child that Trayvon was. Roosevelt’s Mock Trial students hope that this will be the first of many events where they as youth will be central in the vision and action for the changes they want in our community and society.

Moé Yonamine teaches at Roosevelt High School in Portland, Oregon. She is a Rethinking Schools editor.