By Renée Watson

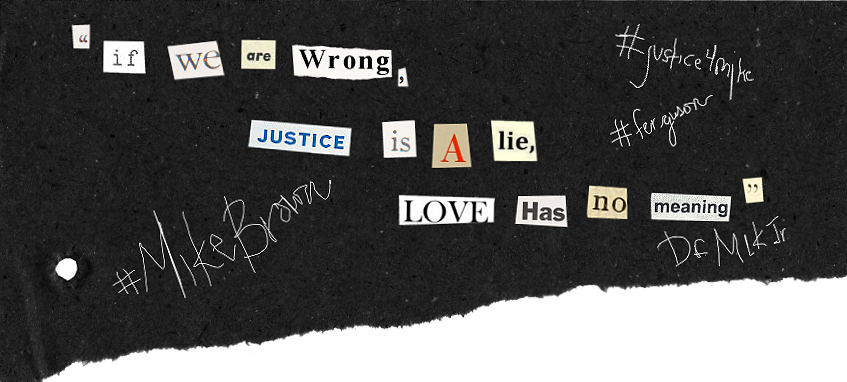

This time last summer, I researched articles and collected poems about police brutality, racial profiling, and the murders of black men in the United States. The George Zimmerman verdict was fresh on my mind and I wanted to talk about it with my students once school was back in session. I revised a lesson I had taught six years prior on the murder of Sean Bell that asked young people to turn their pain into poetry (http://www.rethinkingschools.org/archive/23_01/sean231.shtml). And now, here I am again, swapping out the articles I used last year on Trayvon Martin with articles about Mike Brown. I have accepted that I may have to teach this lesson every school year.

I am moved by the Twitter handle, #FergusonSyllabus. It gives me hope to know that educators are willing to have difficult conversations with their students, that poetry and essays will be written to honor the lives of those we’ve lost to senseless murder, that healthy discussions will happen across the country between young people. But I hope we go past one lesson, one unit. I urge us to think about how our classrooms and curricula challenge or support stereotypes, how they liberate or stifle our young people. It is not enough to teach one “social justice” unit. My hope is that we move from isolated lessons and units and commit to creating classrooms that intentionally and consistently provide opportunities for learners to not just know about injustice but fight against it and begin creating a just world.

As educators, we are not just teaching science, math, or English. We teach culture and norms. Our students notice the jokes we laugh at and the ones we don’t. They pick up on our low expectations when we overly praise them as if we are surprised they could actually complete the assignment we gave them. They are learning whose stories matter by the books we assign. They see who we kick out of class and who we give second and third chances to.

Black students are three and a half times more likely to be suspended from school than white students (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/tavissmiley/tsr/education-under-arrest/school-to-prison-pipeline-fact-sheet/). The school-to-prison pipeline is a very real epidemic and I believe it has common denominators with the issues of police brutality and racial profiling. Some of them being the assumptions, fears, and dehumanizing beliefs we have about black boys and men. So when educators ask, “What can I do?” and “How do I teach about Ferguson?” My response is don’t just teach about Mike Brown and Ferguson. Take time to comb through your syllabus, to look at the posters hanging on your wall, to review and maybe revise your classroom management strategies and practices. Make sure your classroom represents the world in which our young people live. Make sure your policies mirror the values you hold as an educator. Address the assumptions you have about your students and be intentional about getting to know them as individuals.

This is not advice for black teachers only or for teachers who teach students of color. I believe these are good teaching practices, in general, and just as important for teachers who teach in all white or predominantly white schools. On the blog, Manic Pixie Dream Mama, a white mother writes:

My boys will carry a burden of privilege with them always. They will be golden boys, inoculated by a lack of melanin and all its social trapping against the problems faced by Black America.

For a mother, white privilege means your heart doesn’t hit your throat when your kids walk out the door. It means you don’t worry that the cops will shoot your sons.

It carries another burden instead. White privilege means that if you don’t school your sons about it, if you don’t insist on its reality and call out oppression, your sons may become something terrifying.

Your sons may become the shooters.

This mother thinks about the possibility of the shooters being in her home. I think of the possibility of the shooters being in our classrooms.

That is why I so adamantly believe that social justice pedagogy is not for students of color only. We need all young people to examine our world, critique it, and vow to change it. I believe children should be nurtured to practice empathy, to not judge one another based on the color of skin. I believe teachers should commit to exposing our young people to a variety of stories, that we vow to take a personal inventory and deal with our own biases and not be confined to what Chimimanda Adichie calls the “single story.” (http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story).

I am grateful for movements like #WeNeedDiverseBooks, and publishers like Lee and Low Books who understand that young people—all people—need to read a “mix of ‘mirror’ books and ‘window’ books…books in which they can see themselves reflected and books in which they can learn about others.” Lee and Low’s checklist for creating diverse libraries asks the following questions: Do all your books featuring black characters focus on slavery? Do all your books about Latino characters focus on immigration? Are all your LGBTQ books coming out stories? Do you have any books featuring diverse characters that are not primarily about race or prejudice? The list also reads, “Consider your classic books, both fiction and nonfiction. Do any contain hurtful racial or ethnic stereotypes, or images…If so, how will you address those stereotypes with students? Have you included another book that provides a more accurate depiction of the same culture? (http://blog.leeandlow.com/2014/05/22/checklist-8-steps-to-creating-a-diverse-book-collection/ ).

These are important questions. And no, I don’t believe that diverse books alone is the magical answer to America’s race problem. But I do believe that sharing stories is one way to humanize marginalized people, it is a way of seeing past labels.

I believe we are gatekeepers. I believe that what we bring into the classroom, in both content and attitude, will impact our young people in ways we might never personally witness.

As we think about teaching about Ferguson, let us remember to share with our young people stories of courage, hope, and solidarity.

Here are four activities that can help young people learn about the historical context while also giving them an opportunity to take action—even if the action is small.

- Teach about Emmett Till. Discuss Mamie Till Mobley and her decision to let Jet Magazine publish the photo of Emmett and how that got the nation’s attention. Ask students to think about the role of social media in the murders of Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown. What can they do via social media to continue to bring awareness about what is going on in Ferguson?

- Bring in music that addresses social issues (“What’s Going On” by Marvyn Gaye, “Rebel” by Lauryn Hill, etc.). Have students write a song or poem that asks a question or responds to the injustices of today.

- View Norman Rockwell’s civil rights paintings and ask students to create a work of art and display the work on a bulletin board in the hallway.

- Find poems of hope (examples: “Still Here” by Langston Hughes, “For My People” by Margaret Walker, “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou, “won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton) and discuss the timeline of African American history in the United States. How does each generation gain hope from the previous generation? What hope can they pass on?

Please do teach about Mike Brown. But don’t stop there.

Renée has worked as a writer in residence for several years teaching creative writing and theater in public schools and community centers through out the nation. Her articles on teaching and arts education have been published in Rethinking Schools and Oregon English Journal. In June 2014, Renée gave lectures and talks at many renown places, including the United Nations Headquarters and the Library of Congress. Her forthcoming YA novel, This Side of Home (Bloomsbury), will be available February 2015.