by the editors of Rethinking Schools

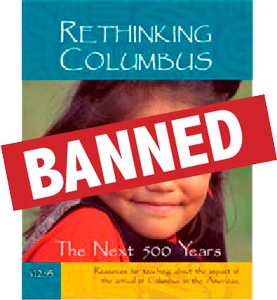

As many Rethinking Schools readers know, in January Tucson school officials ordered our book Rethinking Columbus removed from Mexican American Studies classes, as part of their move to shut down the program. In some instances, school authorities confiscated the books during class—boxed them up and hauled them off. As one student said, “We were in shock. . . . It was very heartbreaking to see that happening in the middle of class.”

Other books banned from Mexican American Studies classes included Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Rodolfo Acuña’s Occupied America, and Elizabeth Martínez’ 500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures.

We are in good company.

Many commentators focused on the outrageous act of banning books. But the books were merely collateral damage. The real target was Tucson’s acclaimed Mexican American Studies program, whose elimination had long been a goal of rightwing politicians in Arizona. Their efforts ultimately found legislative expression in House Bill 2281, passed shortly after Arizona’s now-infamous Senate Bill 1070, which mandated racial profiling in immigration enforcement. National outrage focused on SB 1070, with barely any attention paid to HB 2281, a law whose origins lay in the same racial prejudice.

The law’s punchline comes in Section 15-112, which prohibits any courses that “advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.” Tom Horne, the former Arizona superintendent of public instruction and the state’s current attorney general, sums up the law’s curricular dogma: “Those students should be taught that this is the land of opportunity, and that if they work hard they can achieve their goals. They should not be taught that they are oppressed.”

Of course, by “those students,” Horne means Mexican Americans. To assert that oppression is a myth, especially the oppression of Mexican Americans, one must be historically illiterate—or lying. A few examples: The state of Arizona itself was acquired by the United States through invasion, war, and occupation—an enterprise justified by notions of racial supremacy. As the Congressional Globe insisted in 1847, seizing Mexican territory for the United States “is the destiny of the white race. It is the destiny of the Anglo-Saxon race.” A 1910 government report, quoted in the now-banned Occupied America, concluded: “Thus it is evident that, in the case of the Mexican, he is less desirable as a citizen than as a laborer.” Today in Arizona, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty, more than twice the percentage of Mexican American children live in poverty as white children: 64 percent to 30 percent. And Mexican Americans are twice as likely as whites to be incarcerated.

To demand that students think purely in terms of individuals and ignore race, class, and ethnicity is to enforce stupidity as state policy. Moreover, to erase solidarity from students’ conceptual vocabulary leaves them ignorant of how people have struggled to improve their lives—and have made the world a better place. Proposing that we rise purely as individuals—“I think I can, I think I can”—may be a comforting notion for social elites, but it’s simply wrong, empirically as well as morally. Outlawing solidarity benefits only those whose interests are threatened by people organizing for greater equality.

Today’s curricular ethnic cleansing in Arizona is the product of a toxic blend of fear and racism. Here’s Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal on NPR’s Tell Me More: “These issues are going to be huge philosophical issues for the United States as we become—as our whole racial makeup changes. And we need to know that there are a lot of serious concerns about how you educate kids, the values that you pass on to them.”

Translation: Whites are becoming a minority in this country. If children of color are taught to question structures of wealth and power; to think in terms of race, class, and ethnicity; to learn the history of solidarity and organizing; and come to see themselves as activists . . . well, the United States will be a very different place. In his 2010 campaign ads, Huppenthal promised to “Stop la raza.” Destroying Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program is one way he intends to keep that promise.

For rightwing politicians like Tom Horne, John Huppenthal, and Gov. Jan Brewer, it’s not the failure of the Mexican American Studies program that they fear—it’s the program’s success. According to Tucson’s own director of accountability and research, “there are positive measurable differences between MAS students and the corresponding comparative group of students.” Mexican American Studies students score higher on standardized reading, writing, and even math tests than their peers, are more likely to graduate from high school, more likely to attend college, and—a feature that doesn’t show up in the data printouts—are more likely to see themselves as activists.

This kind of education is a threat to those who would prefer Mexican Americans as quiet and compliant workers. Mayra Feliciano, a co-founder of the Tucson student activist group UNIDOS and an alumna of the Mexican American Studies program, told Jeff Biggers in an interview, “As long as people like Superintendent John Huppenthal and TUSD board members are afraid of well-educated Latinos, they will try to take away our successful courses and studies.”

Following one of Biggers’ fine Huffington Post blog posts on the Mexican American Studies program, one respondent, “Tucson Don,” directed his comments to a student Biggers had quoted:

“Hey Chicka, nobody is stopping you from learning about your own culture. But you now live in the US, and you can do that on your own time and your own dime! We Americans want you to learn to read (English), write (also in English) and be able to add, subtract, multiply, and divide well enough to complete a business transaction without needing a computer to tell you that a $1.99 Egg McMuffin plus a $.99 hash browns and free coffee adds up to $2.98 before tax.” Tucson Don and his ilk echo the century-old words quoted above: the Mexican American is “less desirable as a citizen than as a laborer.”

This is the “gutter education,” as the youth of South Africa used to call it, that the Mexican American Studies program was designed to supplant. Those who have read the letters and articles online by MAS teachers Curtis Acosta and Maria Federico Brummer, or who have seen the excellent film Precious Knowledge, know that this is not a program that teaches hate or “resentment.” It sparks curiosity, honors students’ lives, demands academic excellence, prompts critical thinking, invites activism, and imagines a better world.

Its ethos of love, mutual respect, and solidarity is expressed in the poem that has come to symbolize the program, borrowed from Luis Valdez’ 1971 Mayan-inspired “Pensamiento Serpentino”:

In Lak’ech (I Am You or You Are Me)

Tú eres mi otro yo.

You are my other me.

Si te hago daño a ti.

If I do harm to you.

Me hago daño a mí mismo.

I do harm to myself.

Si te amo y respeto,

If I love and respect you,

Me amo y respeto yo.

I love and respect myself.

We encourage Rethinking Schools readers to join the national solidarity campaign, “No History Is Illegal,” launched by the Teacher Activist Groups (TAG) network, to teach about this important struggle. In fact, Tucson’s program should not only be defended, it should be extended: We should demand that local, state, and federal policies support more multicultural, anti-racist education initiatives. As the U.S. school curriculum becomes increasingly shaped by giant multinational publishing corporations, it’s essential to stand up for—and spread—community-supported, social justice curriculum, as exemplified by Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program.

In Lak’ech. An injury to one is an injury to all.

Related Resources:

The Line Between Us explores the history of U.S-Mexican relations and the roots of Mexican immigration, all in the context of the global economy. And it shows how teachers can help students understand the immigrant experience and the drama of border life.

The Line Between Us explores the history of U.S-Mexican relations and the roots of Mexican immigration, all in the context of the global economy. And it shows how teachers can help students understand the immigrant experience and the drama of border life.

A People’s History for the Classroom helps teachers introduce students to a more accurate, complex, and engaging understanding of U.S. history than is found in traditional textbooks and curricula.

A People’s History for the Classroom helps teachers introduce students to a more accurate, complex, and engaging understanding of U.S. history than is found in traditional textbooks and curricula.