By Barbara Miner

Susan Endress is into her second decade of demanding, cajoling, threatening, and doing whatever it takes to ensure that Milwaukee schools honor the rights of special education students.

On a recent afternoon, she shakes her head in weary frustration as she reads a summary of the special ed services provided (or, more likely, not provided) by Milwaukee voucher schools that receive public dollars yet operate as private schools.

“What do they mean, they can’t serve children more than a year below grade level?” she says of one school’s description. “That’s terrible.”

“Oh, here’s a good one,” she says as she continues reading. “‘We cannot serve wheelchair-bound students.’ And look at this one, it cannot serve ‘students who are unable to climb stairs.'”

She turns to a young man in a wheelchair working in the office with her at Wisconsin FACETS, a special education advocacy and support group for families. “Make sure you’re bound to your wheelchair,” she tells him good-naturedly. “And better learn to climb stairs.”

Her moment of humor over, Endress turns serious again.

“You have to remember, it’s only been a little over 25 years that special needs children have even had the right to attend a public school,” she says. “And here we’re moving backwards with the voucher schools, not forward. I’m personally scared to death of where this might lead.”

Milwaukee’s voucher program, the country’s oldest, has long been seen as a prototype for what, in essence, is a conservative strategy to privatize education under the guise of “choice.” With the U.S. Congress poised to start the first federally funded voucher program next fall in the Washington, D.C., schools, vouchers have once again jumped to the fore of educational debate.

Although Milwaukee’s voucher schools receive tax dollars, they operate as private schools and thus can ignore almost all of the requirements and accountability measures that public schools must follow. They do not, for example, have to hire certified teachers, nor administer the same tests as public schools, nor report their students’ academic achievement.

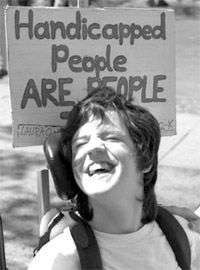

Nor do they have to provide the special education services required of public schools. While voucher supporters portray vouchers as a new Civil Rights Movement, disability activists see a different reality.

Jim Ward, president of ADA Watch and the National Coalition for Disability Rights in Washington, D.C., warns that voucher programs threaten the rights of students with special needs. He cites a 1998 survey by the U.S. Department of Education that between 70 and 85 percent of private schools in large inner cities would “definitely or probably” not participate in a voucher program if required to accept “students with special needs such as learning disabilities, limited English proficiency, or low achievement.” Among religious schools, the figure was 86 percent.

“The Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision struck down ‘separate but equal’ schools, but voucher programs threaten to usher in a new form of segregation,” Ward warns.

Milwaukee’s voucher program shows that Ward’s fears are well-founded. At a time when the percentage of special education students in the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) hovers around 16 percent and is projected to reach 19 percent by 2007, voucher schools are not legally obliged to provide special education services to their students.

The only official data on special ed and Milwaukee voucher schools is from a 2000 report by the Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau. It found that only 3 percent of the students in voucher schools in 1998-99 had previously been identified as needing special education services. It also noted that voucher schools likely served children with “lower-cost” needs such as speech, language, and learning disabilities.

Current data is sketchy, at best, because voucher schools do not have to collect or release information. The little information that’s available paints a bleak picture.

A voluntary, unaudited survey by the Public Policy Forum in October 2002 found that almost half of the voucher schools provide no special ed services, even for students with mild learning disabilities. A significant number reported programs such as “Title I” or “smaller classes” that are generally not considered special education services. Some note that they work with MPS, which provides the special education services. One school said that special needs students are served through its “Jesus Cares Ministry.”

A look at a website hosted by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (www.uwm.edu/EPIC) is even more revealing. The site has information on most Milwaukee schools, private and public, and has a section where schools report on “categories of students which the school cannot serve.” Some voucher schools do not report anything. Or, like Marquette University High School, they say the information is “n/a.”

Many voucher schools succinctly note that they cannot serve “LD, ED, children with physical disabilities”-referring to learning disabled (LD) and emotionally disabled (ED). Some explanations are more elaborate. Blessed Sacrament, for example, says: “We believe that students who are 2-3 years below grade level cannot be realistically brought up to grade level because we do not have a tutorial/learning center to accommodate their needs. Students who have severe emotional or behavioral problems need specific programs to assist them-we do not have a counselor or social worker.”

Some schools send mixed messages. St. Adelbert says: “We do not have specific services for ED students though we do have ED students. We do not have an elevator. However, we do have physically disabled students. We do have sight- and hearing-impaired students. We cannot service severe MR [mental retardation].”

A few voucher schools note they provide some special ed services, in particular for children with mild learning or physical disabilities. St. Gregory the Great, for instance, says, “We are able to accommodate most children with learning disabilities.”

Services for special education students seem to be particularly limited at voucher high schools. Messmer, which had 398 voucher students last year, specifically notes on the EPIC website that it has “no special [ed] classes.” Learning Enterprise, which had 175 voucher students, likewise said it cannot serve special education students. Pius XI, meanwhile, with 199 voucher students last year, is making an effort. While it says it cannot serve ED or EMR [educable mentally retarded] students, it provides services for LD students.

The Milwaukee voucher program is expected to cost about $76 million in taxpayer dollars this year, bringing the total to almost $350 million since its inception in 1990. This year it will serve almost 13,000 students, providing up to $5,882 for each child.

Funding Special Ed

Voucher proponents sometimes argue that voucher schools do not provide special education services because they do not get money to do so. But Endress of Wisconsin FACETS doesn’t buy the money argument, whether it comes from public schools, charter schools, or voucher schools.

She understands why all schools may not be equipped to deal with students needing a full-time aide, such as medically fragile students or those with multiple physical, emotional, and medical needs. But such students are the exception, she says. Most special education students can be served without extraordinary accommodations.

“The main thing they have to do is have a teacher on staff that is licensed in special education that is cross categorical,” she says. “There is no reason why these voucher schools can’t have just one teacher. Think of all the support they could provide not just the students but also other teachers. To me, it just makes good educational sense.”

The money argument assumes that public schools receive adequate funding for special education. But they don’t. In MPS, for example, special ed spending is about $164 million this year, according to Michelle Nate, director of finance. Since the state and federal governments reimburse only 66 percent of that money, MPS must take $55 million from its overall budget to fund special education.

The Milwaukee Archdiocese, which oversees the largest bloc of voucher schools, does not have figures on special education. Nor does the Archdiocese provide special education teachers for its schools. Dave Prothero, superintendent for the Milwaukee Archdiocesan schools, says special education issues are dealt with at the school level. “Any parent that calls and says that their child has special needs, the response will be, ‘Please come in to the school and talk about the specific needs of your child to see if we can meet those needs.'”

Special education experts, based on anecdotal evidence, say this often means that special ed children are “counseled out” of applying, or encouraged to leave if already enrolled, on the grounds that the school is not a good match.

“I think they are oftentimes discouraged from the very beginning,” says Dennis Oulahan, an MPS teacher who provides special education assessments for bilingual children in both private and public schools. “The message might be, ‘Don’t apply.'”

Voucher schools are legally prohibited from discriminating in admissions against children with special needs and are only required to provide services that require “minor adjustments.” Until the definition of “minor adjustments” is tested in the courts, it is doubtful that voucher schools will significantly change their practice.

As Oulahan notes, “Voucher schools don’t have to deal with special ed. They are private schools. And as long as they don’t have to deal with it, I don’t think they are going to volunteer.”

Barbara Miner ( barbaraminer@ameritech.net ) is a freelance writer and former managing editor of Rethinking Schools.

Winter 2003