By the Editors of Rethinking Schools

No teacher education program could have prepared us to confront the emotionally shattering events of Sept. 11. We began school that morning in one era, but left that evening in a different era – one filled with sorrow, confusion, and vulnerability. No matter what age student we work with, we found ourselves rethinking and revising our lesson plans, if not our life plans.

In this special edition of Rethinking Schools, we offer two things: a range of perspectives from educators seeking to respond to students’ emotional and intellectual needs in the current crisis; and background articles that provide social and historical context to guide our work as educators.

These efforts are tentative, intended more as point of departure than as final statement. We welcome feedback.

Although the events of Sept. 11 changed many things, the core principles that guide our curricular response were already in place:

Educators need to nurture student empathy. As Alfie Kohn urges in his article, page 5, “Schools should help children locate themselves in widening circles of care that extend beyond self, beyond country, to all humanity.” In these pages, teachers use poetry and letter writing to prompt students to imagine themselves as part of a human, not just American, family (page 7 and page 9). Globalizing empathy can be especially difficult when textbooks and pundits alike use “us,” “we,” and “our” to promote a narrow nationalism. It’s our job to reach beyond this chauvinism.

If there has been a “good” effect of Sept. 11, it has been the outpouring of generosity, self-sacrifice, and solidarity. We should help students make these “circles of care” as wide as possible.

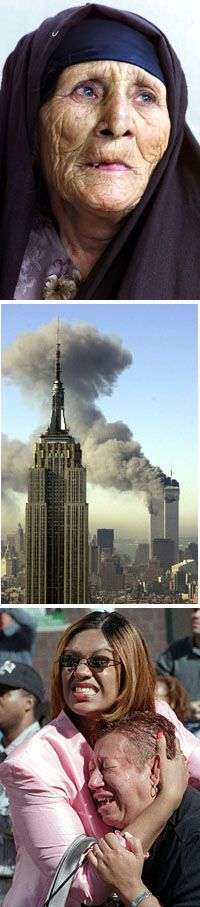

We need to be multicultural and anti-racist. This stems both from a commitment to the kind of world we want to live in – one where the lives of people of all races and cultures are equally valued – as well as from a methodological imperative: The only way we can make sense of this moment in history is through a multicultural lens. We hope this sensibility weaves throughout this special issue, from articles about racist attacks on people of Middle Eastern or South/Central Asian descent (page 17), to explorations of Islam (page 6), to perspectives on U.S. policy as seen by others around the world (page 9).

Crisis will always be used to further agendas of racial privilege. In multiple ways this is a dangerous time: immigrants are made to feel more fearful; as military budgets swell, programs that could ameliorate racial inequality suffer; the “war against terrorism” emboldens defenders of the status quo who have new tools to stifle racial justice activism.

A multicultural inquiry always prompts teachers to ask: Who benefits? Who suffers? In its critique of the new anti-terrorism law – the high-sounding USAPatriot Act – the ACLU spells out in chilling detail how the federal government has used this crisis to seize greater power and to erode civil liberties (page 16). In this same vein, U.S. officials have sought to discredit the burgeoning global justice movement, conflating activism with terrorism, claiming that those who oppose “free trade” oppose freedom.

We need to ask the deep “Why?” questions. Nothing can justify the heinous attacks of Sept. 11. But to unequivocally condemn these attacks does not relieve us of the responsibility to explain them. A photograph from a demonstration in Pakistan that Bob Peterson uses with his students urges, “Americans, Think! Why You Are Hated All Over The World!” Several articles in this issue suggest some U.S. policies that have led to such antipathy, especially in the Middle East: U.S. support for anti-democratic regimes, and the overthrow of more democratic ones, like Iran’s Mossedegh in 1953; the tenacity of U.S. support for sanctions against Iraq that have killed hundreds of thousands of children; U.S. arming of Israel and its support of Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. Beyond such policies, teachers need to engage students in questioning the global economic system. Its relentless emphasis on profit continues to impoverish millions around the world, dislocating cultural patterns and making people receptive to repressive fundamentalisms of all kinds.

We need to enlist students in questioning the language and symbols that help frame how we understand global events. Terms like terrorism, freedom, liberty, patriotism, and unity evoke powerful images, and consequently must be critically examined. When Osama bin Laden was fighting Soviet troops in Afghanistan, President Reagan called him a “freedom fighter.” Now he’s a terrorist. In the 1980s the U.S. government considered Nelson Mandela a terrorist. Now he’s a statesman. Language is marshaled for political ends, and students need to reflect on this (page 12).

Educators need to honor dissent and those who challenge power and privilege as they work for justice.Too often, students are denied knowledge about individuals and social movements that have made the world a better place. They learn that obedience is a synonym for patriotism and that citizenship gives you the right to vote and do as you’re told. The articles in this issue of Rethinking Schools propose a more activist vision. They urge students to question basic premises about terrorism and war. They give students permission to think independently from the Official Story.

Clearly, these principles will play out differently in an early childhood setting than they will in a high school classroom. But they are the starting point for how we propose to help our students confront an era fraught with violence and uncertainty. They remind us that if a better world is possible, we’re the ones who have to build it.

Winter 2001 / 2002