There’s no guarantee of quality in Milwaukee’s voucher schools

By Barbara Miner

Reporters often ask me for a 30-second sound bite on the quality of the private schools in Milwaukee’s 15-year-old voucher program, the nation’s oldest. I usually say there are good schools—especially those with stricter requirements and a history that pre-dated vouchers—lots of average schools, and some not-so-great schools.

That answer is history. It’s increasingly clear that a disturbing number of voucher schools are outright abominations.

An investigation this June by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel found problems in some voucher schools that—even to those numb to educational horror stories—break one’s heart. No matter how severe one’s criticisms of the Milwaukee Public Schools, nothing is as abysmal as the conditions at some voucher schools.

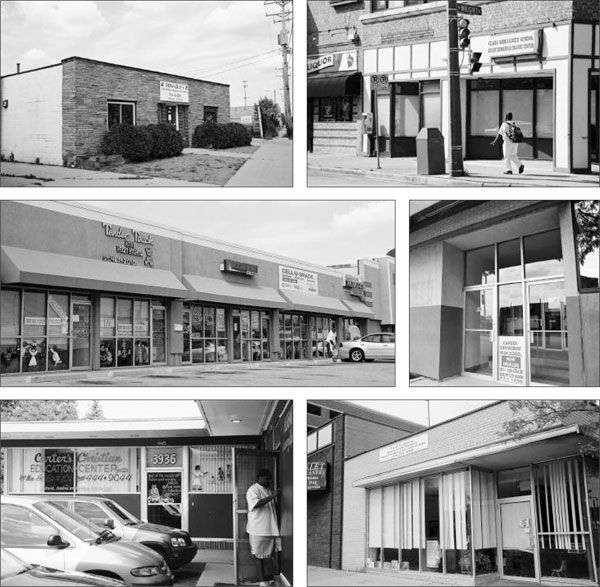

Some of them had high school graduates teaching students. Some were nothing more than refurbished, cramped storefronts. Some did not have any discernable curriculum and only a few books. Some did not teach evolution or anything else that might conflict with a literal interpretation of the Bible.

At one school, teacher and students were on their way to McDonald’s. At another, lights were turned off to save money. A third used the back alley as a playground.

One school is located in an old leather factory, another in a former tire store, a third is above a vacuum cleaner shop and hair salon.

As one of the reporters said, “I think we expected from the start to see some strong schools and some weak ones. But seeing firsthand the effect that troubled schools can have on children’s futures and lives was disturbing.”

Overall, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel estimated that about 10 percent of the schools visited demonstrate “alarming deficiencies” without “the ability, resources, knowledge or will to offer children even a mediocre education.”

That’s a cautious estimate. First of all, reporters made pre-arranged visits, giving schools time to put their best faces forward. Second, nine of the program’s 115 schools —an additional 8 percent—refused to allow reporters in.

Built-in Problems

It would be reassuring if these shortcomings were an aberration or mistake. Unfortunately, they are part and parcel of the program’s structure.

Ever since the program began in 1990, its conservative backers have argued that free-market forces will provide sufficient checks and balances and that the voucher schools should not have to follow the rules governing “government monopoly schools” (more commonly known as “public schools”). As a result, Milwaukee’s voucher schools are exempt from any number of guidelines, such as hiring certified teachers, testing students, or publicly releasing data on student achievement.

Milwaukee’s voucher program began, nominally as an experiment. It initially served 337 students in seven schools. The program expanded rapidly when religious schools were allowed to join in 1998. At the end of the 2004-05 school year, almost 15,000 students in 115 schools were taking part.

Since the program’s start, voucher schools have received a total of almost half a billion dollars in taxpayers’ money. Yet, as one of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporters has noted, “The lack of research and data is stunning.”

Through the years, voucher horror stories have occasionally cropped up—usually when a school or school administrator was caught in a flagrant illegality, parents picketed, or staff walked out because they hadn’t been paid.

Alex’s Academics of Excellence, for instance, operated under the public’s radar screen until its founder was sentenced for tax fraud and it came to light he had previously been convicted of raping a woman at knifepoint. (The school closed last year after a raft of other problems, including two evictions, allegations that staff used drugs on school grounds, and an investigation by the district attorney’s office.)

Free-Market Education

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s investigation, released as a seven-part series, was its first attempt to systematically visit and report on the voucher schools.

The series documented what many had long surmised: The city’s longstanding Catholic and Lutheran schools have, by and large, requirements and oversight that help guarantee a level of quality. All teachers at schools connected with the Catholic Archdiocese, for instance, are required to be either licensed or in the process of getting a license. In addition, schools with broader institutional support, or those founded by seasoned educators, tend to have better quality.

About 50 new schools have been created as a result of the voucher program. A number were established independently by individuals with few educational credentials. These unaffiliated “free-market” schools, created in response to the supply of public voucher money, often have the most problems.

In late August, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel released an online school-by-school summary to supplement its series. The summaries show that a disturbing number of schools are beset by two overriding problems: inadequate facilities and unqualified teachers. (I’ll leave concerns about fraud and scams to the district attorney’s office.)

At the Sa’Rai and Zigler Upper Excellerated Academy (K4–1), principal Sa’Rai Nance doesn’t even have a teaching license. She said she opened the school after she had a vision from God. Nance also said that “excellerated” is a fusion word combining accelerated and excellent and is “spelled wrong on purpose.” The word “upper” refers to “the upper room where Jesus prayed.”

Carter’s Christian Academy (K4–1) is described as “essentially a small storefront building with a couple of tiny rooms redone as classrooms. …There were no visible books or toys or paper.” The school’s two teachers have high school diplomas, and the highest-paid teacher makes $8 an hour.

At Grace Christian Academy (K4–7), one staff member privately told reporters “that there was no curriculum. Several classrooms were using worksheets downloaded from the Internet. …There were few books or schools materials on [the] shelves or anywhere in sight.” In at least one case, the summary continued, “the teacher was giving inaccurate scientific information to kids. [Principal Reginald] Armstrong says teachers use Biblical principles. He taught his class the story of Adam and Eve recently, from a literalist position.” Armstrong has a teaching license, but none of the other teachers do.

Unfortunately, little happened over the summer to ensure that voucher schools meet minimal levels of educational accountability. A few financial rules were tightened up, and the state Department of Public Instruction was given limited ability to intervene when there are safety concerns. But, as the Journal Sentinel reported, “The new rules do not give the state any increased authority in overseeing the actual educational programs of schools.”

The biggest development in Milwaukee’s voucher program? This fall, an additional 17 voucher schools opened.

Barbara Miner (barbaraminer@ameritech.net), a Milwaukee-based journalist, is a Rethinking Schools columnist.

Fall 2005