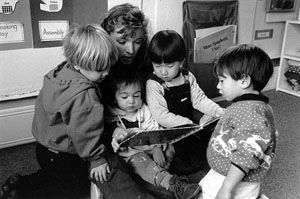

A teacher offers help with understanding how young children may react to tragedy and war.

The following is condensed from a letter that Ann Pelo sent to parents of children at the Hilltop Children’s Center, where Pelo teaches in Seattle. The letter was written shortly after the bombing of Afghanistan began.

By Ann Pelo

“What really matters now is love. Strength, love, courage, love, kindness, love. That is really what matters. There has always been evil, and there will always be evil, but there has always been good, and there is good now.”

-Maya Angelou, poet and author, September 2001.

- These are heavy days, full of the ache of violence, death, and devastation in the United States and in Afghanistan. We adults feel the weight of war in both tangible and subtle ways as our lives shift focus and our hearts open wider and wider. The children feel the weight of war, as well, though they may not have the language for their questions, fears, and uncertainties. We see children wrestling to absorb and understand the violence in New York, Washington D.C., and Afghanistan in a range of ways:

- Children are more fragile these days. Some children are waking at night with bad dreams – children who typically sleep long and soundly through the night. Many parents have described their children as needing extra reassurance; they notice their children clinging to them with unusual intensity, or crying more easily. Some children have expressed fear about unfamiliar people who may be “bad guys.”

- Children are more volatile these days. Kids’ voices are loud and their feelings are raw; we hear children snapping at each other and giving way to quick anger as they play and work together. And there is a lot more physical conflict.

- Children are playing about and trying out violence. We’ve seen children intentionally break or damage other children’s block and Lego constructions, something that hadn’t happened until recent weeks. Gun play and “bad guy” play are ever-present at our school, and I’ve heard from some parents that they’ve seen their children take up gun play at home in new and startling ways. There’s a recurring game in our classroom in which firefighters are trapped in a burning building and are hurt and killed before the rescue workers can reach them. Children build tall towers with blocks and knock them down, over and over and over. Children have begun to make poison foods in their play and feed them to bad guys; several days last week, children hunted down and captured bad guys, throwing them into the oven to “roast and cook and eat them for supper.”

WHAT WE CAN DO

Here are some thoughts about how parents and teachers can support children during this time of unrest and pain:

- Engulf the children in tenderness. At home, create time for long, cozy evenings on the couch with a pile of good books to read together; make dates for baking yummy treats together; linger over family photos and home videos that anchor your child in the joys and safety of your family. Your child may ask for your help with things that you know she can do by herself; this is a great time to offer that extra help. If your child seems particularly edgy, pushing limits and testing boundaries, it may help to snuggle up together for a song or a story rather than enforcing the limit just then: your child’s misbehavior may be his way to ask for reassurance. It’ll probably be easier for him to navigate family rules and boundaries after some tender loving from you.

- Affirm children’s feelings, acknowledging that it’s all right to be frightened, confused, or angry. Reassure your child that she or he is safe – and, too, recognize with her or him that there are folks in the world right now who aren’t safe and that we can feel compassion and grief for them. This is a tricky balance: we want to comfort our children, and we want to cultivate in them the compassion and generosity of spirit that will add to a culture of peace.

- Anchor children’s days with familiar rhythms and rituals. And consider creating a new family ritual about peace, or love, or compassion, perhaps lighting a candle, singing a peace song, or inviting the folks gathered at the dinner table to share an image of beauty, an experience of kindness, or an expression of love.

- Ask your child periodically what she thinks is happening and what she is hearing about the war to open up opportunities for her to express her ideas. It’ll be helpful for your child if you simply listen and acknowledge her thinking, rather than correcting her misunderstandings as she talks; after she’s had a chance to share her thinking, you can share your understandings of and feelings about what’s happening.

- Monitor gun play and “bad guy” play. This play provides children with a way to gain a sense of control and power; as I watched the children in my classroom capture, roast, and eat “bad guys” last week, I was struck by the power in their play: they captured and disarmed bad guys and swallowed their power, taking it into their bodies, conquering it absolutely. You might want to add new perspectives to his play about bad guys, hoping to shift him from one-dimensional understandings to an expanded sense of bad guys as fully human people. You can pose questions like: What does the bad guy’s family do while he’s fighting? How can you get the bad guy to listen to you?

- Stay alert for issues of racism and bias. Children are likely absorbing both the subtle and the overt racist images in our culture that define “bad guys” as people with olive-colored or brown skin, an Arabic accent or language, who dress in long, flowing gowns and wrap their heads in cloth, and who pray in mosques. When your child expresses a biased understanding, it’s important to counter it right away. For example, if your child comments that “People who talk funny are bad guys,” you might intervene to say: “To say someone talks funny is not okay. People talk differently because people in our city, country, and world speak different languages. Sometimes talk sounds funny to us when we haven’t heard it before; we’re not used to the sounds of a new language.”

- Teach peace to children. Share stories of peace heroes. Continue to emphasize the importance of resolving conflicts in ways that honor the needs of everyone involved in the conflict. Talk about peace as an action, rather than as a passive absence of conflict.

Ann Pelo has taught at Hilltop Children’s Center for 10 years and is co-author, with Fran Davidson, of That’s Not Fair: A Teacher’s Guide to Activism with Young Children (Redleaf Press, 2000.)

Winter 2001 / 2002