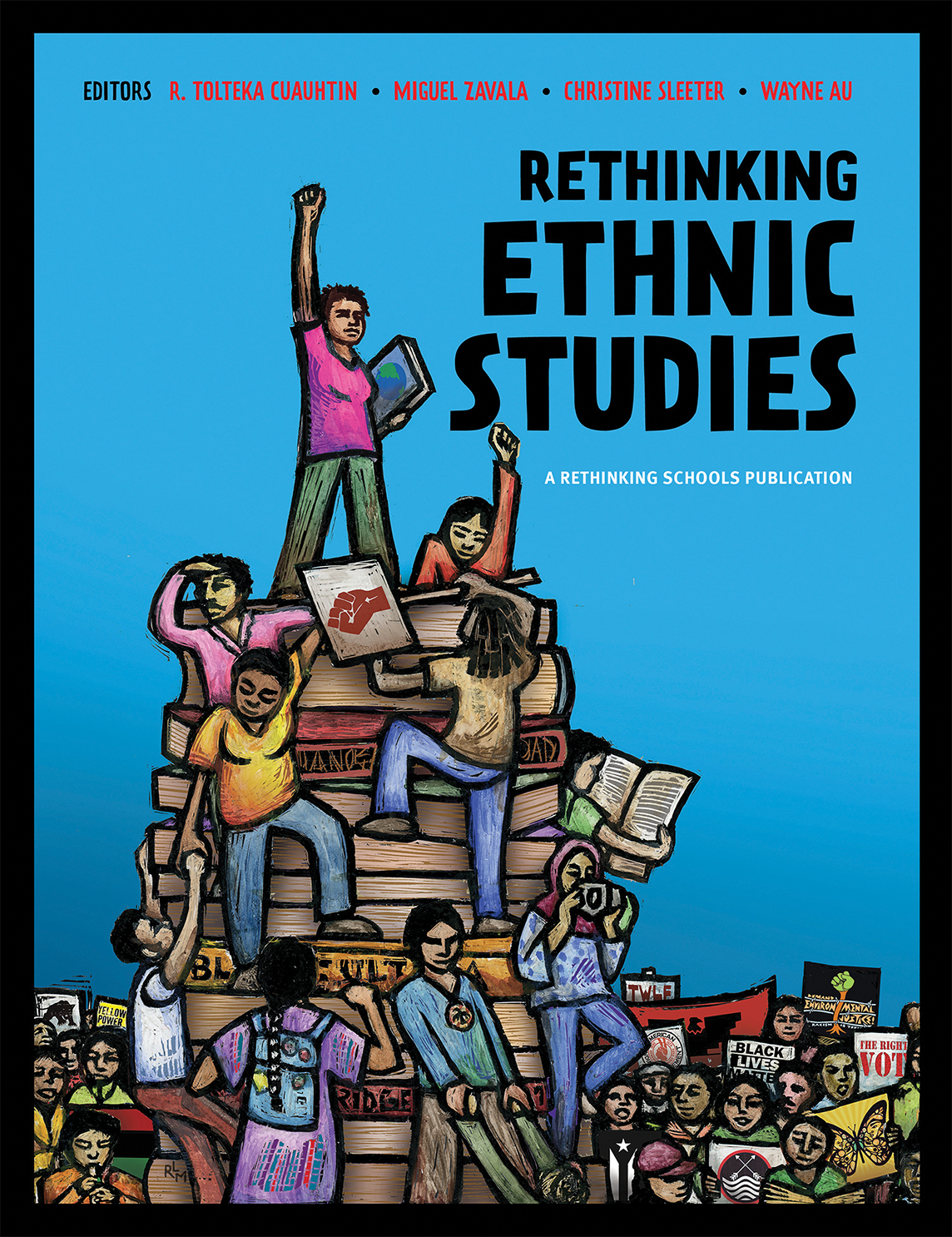

As part of a growing nationwide movement to bring Ethnic Studies into K-12 classrooms, Rethinking Ethnic Studies brings together many of the leading teachers, activists, and scholars in this movement to offer examples of Ethnic Studies frameworks, classroom practices, and organizing at the school, district, and statewide levels. Built around core themes of indigeneity, colonization, anti-racism, and activism, Rethinking Ethnic Studies offers vital resources for educators committed to the ongoing struggle for racial justice in our schools.

2019 GOLD WINNER, Foreword INDIES Awards, education category

“This book is food for the movement. It is sustenance for every educator committed to understanding and enacting Ethnic Studies. We take this gift as a guide for the needed work ahead.”

Django Paris

James A. & Cherry A. Banks Professor of Multicultural Education, University of Washington

“Ethnic Studies as a field is about a half century old. Some may think it has outlasted its usefulness. However, in these times with a resurgence of hate crimes and vicious rhetoric, we need clear and cogent understandings about race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, culture, ability, religion and all kinds of human differences. This volume lifts our discourse and our discernment. It is a significant contribution to our understanding of ourselves and each other.”

Gloria Ladson-Billings

Professor Emerita University of Wisconsin-Madison,

President, National Academy of Education

“Rethinking Ethnic Studies provides an excellent resource for teachers, students, and activists who wish to critically understand and engage the fundamental issues and questions that frame the field. The volume brings together theory and practice in ways that are both engaging, as well as extremely practical for classroom use. Overall, this is precisely the book that Ethnic Studies educators and advocates have been waiting for—a powerful pedagogical contribution that embodies a genuine tribute to an abiding historical commitment to cultural democracy within education and the larger society.”

Antonia Darder

Leavey Endowed Chair of Ethics & Moral Leadership

at Loyola Marymount University

“Rethinking Ethnic Studies is one of the most comprehensive, insightful, critical, and important books on Ethnic Studies in education. It charts a bold new path forward for the current Ethnic Studies resurgence that both builds off of and develops the scholar/activist history of the discipline.”

Nolan L. Cabrera, PhD

University of Arizona

“In this moment of rising visibility and normalization of systemic, intersectional, and organized racism, we must more deeply understand the legacies of white supremacy, colonization, and imperialism that have long shaped U.S. schools and society, and the equally long legacies of anti-oppressive struggle. With brilliant insight, stirring passion, and evidence for hope, Cuauhtin, Zavala, Sleeter, Au, and dozens of colleagues share here a compelling framework, analyses, and examples of precisely that. Rethinking Ethnic Studies does nothing less than build our collective capacity for rethinking education more broadly.”

Kevin Kumashiro

Author of Bad Teacher!: How Blaming Teachers Distorts the Bigger Picture

Table of Contents:

Section 1: Framing Ethnic Studies

- “The Movement for Ethnic Studies: A Timeline” By Miguel Zavala, R. Tolteka Cuauhtin, Wayne Au, and Christine Sleeter

- “Multicultural Education or Ethnic Studies?” By Christine Sleeter, Joni Boyd Acuff, Courtney Bentley, Sandra Guzman Foster, Peggy Morrison, and Vera Stenhouse

- “Ethnic Studies: 10 Common Misconceptions” By Miguel Zavala, Nick Henning, and Tricia Gallagher-Geurtsen

- “What Is Ethnic Studies Pedagogy?” By Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, Rita Kohli, Jocyl Sacramento, Nick Henning, Ruchi Agarwal-Rangnath, and Christine Sleeter

- “Ethnic Studies Pedagogy as CxRxPx” By R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

- “Counter-Storytelling and Decolonial Pedagogy: The Xicanx Institute for Teaching and Organizing” By Anita E. Fernández

- “The Matrix of Social Identity and Intersectional Power: A Classroom Resource” By R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

- “Creating We Schools: Lessons Learned from Critically Compassionate Intellectualism and the Social Justice Education Project” By Augustine Romero and Julio Cammarota

- “Six Reasons I Want My White Child to Take Ethnic Studies” By Jon Greenberg

- “Revisiting Notions of Social Action in Ethnic Studies Pedagogy: One Teacher’s Critical Lessons from the Classroom” By Cati V. de los Rios

- “The Ethnic Studies Framework: A Holistic Overview” By R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

Section 2: Indigeneity and Roots

- “Collective Healing: Release the Tears, Confront and Bypass the Fear” By Rose Borunda

- “The Kids ‘n Room 36: Cognates, Culture, and the Ecosystem” By Jaime Cuello

- “‘My Family’s Not from Africa—We Come from North Carolina!’: Teaching Slavery in Context” By Waahida Tolbert-Mbatha

- “Barangay Pedagogy: Teaching as a Collective Act” By Arlene Sudaria Daus-Magbual, Roderick Daus-Magbual, Raju Desai, and Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales

- “Do I Need to Mail in My Spit?: The Importance of a Teacher’s Roots in Teaching Ethnic Studies” By Dominique A. Williams

- “Our Oral History Narrative Project” By Aimee Riechel

- “Rethinking Islamophobia: A Muslim Educator and Curriculum Developer Questions Whether Religious Literacy Is an Effective Antidote to Combat Bigotries Rooted in American History” By Alison Kysia

- “Hmong Club: Empowering Us” By Pang Hlub Xiong

- “Critical Family History” By Christine Sleeter

Section 3: Colonization and Dehumanization

- “Burning Books and Destroying Peoples: How the World Became Divided Between ‘Rich’ and ‘Poor Countries'” By Bob Peterson

- “Genocide of Native Californians Role Play” By Aimee Riechel and interview by Miguel Zavala

- “The Advent of White Supremacy and Colonization/Dehumanization of African Americans” By Deirdre Harris

- “Challenging Colonialism: Ethnic Studies in Elementary Social Studies” By Carolina Valdez

- “Cherokee and Seminole Removal Role Play” By Bill Bigelow

- “Sin Fronteras Boy: Students Create Collaborative Websites to Explore the Border” By Grace Cornell Gonzales

- “The Color Line” By Bill Bigelow

Section 4: Hegemony and Normalization

- “Connecting the Dots” By Stephen Leeper

- “History Textbooks—’Theirs’ and ‘Ours’: A Rebellion or a War of Independence?” By John DeRose

- “Learning About the Unfairgrounds” By Katie Baydo-Reed

- “Whose Community Is This?: The Mathematics of Neighborhood Displacement” By Eric “Rico” Gutstein

- “Reclaiming Hidden History: High School Students Face Opposition When They Create a Slavery Walking Tour in Manhattan” By Michael Pezone and Alan Singer

- “Teaching a Native Feminist Read” By Angie Morrill with K. Wayne Yang

- “Teaching John Bell’s Four I’s of Oppression” By R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

- “Ethnic Studies Educators As Enemies of the State and the Fugitive Space of Classrooms” By Tracy Lachica Buenavista, David Stovall, Edward R. Curammeng, and Carolina Valdez

Section 5: Regeneration and Transformation

- “Reimagining and Rewriting Our Lives Through Ethnic Studies” By Roxana Dueñas, Jorge López, and Eduardo López

- “Regeneration/Transformation:Cultivating Self-Love Through Tezcatlipoca” By Mictlani Gonzalez

- “Happening Yesterday, Happened Tomorrow: Teaching the Ongoing Murders of Black Men” By Renée Watson

- “We Have Community Cultural Wealth!: Scaffolding Tara Yosso’s Theory for Classroom Praxis” By R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

- “Standing with Standing Rock: A Role Play on the Dakota Access Pipeline” By Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

- “Tipu: Connections, Love, and Liberation” By Curtis Acosta

- “Teaching Freire’s Levels of Consciousness: A Lesson Plan” By Jose Gonzalez

- “Chicana/o-Mexicana/o Resistance and Armation in the Post-Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Era: Curriculum Unit Narrative” By Sean Arce

Section 6: Organizing for and Sustaining Ethnic Studies

- “Moving Ethnic Studies from Theory to Practice: A Liberating Process” By Guillermo Antonio Gómez and Eduardo “Kiki” Ochoa

- “Missing Pages of Our History” By Kaiya Laguardia-Yonamine

- “The Emergence of the Ethnic Studies Now Coalition in Yangna (Los Angeles) and Beyond: Two, Three, Many Tucsons” By Guadalupe Carrasco Cardona and R. Tolteka Cuauhtin

- “The Struggle for Ethnic Studies in the Golden State: Capitol City Organizers and Activists” By Rubén A. González, Maribel Rosendo-Servín, and Dominique A. Williams

- “Ethnic Studies in Providence Schools” By Karla E. Vigil and Zack Mezera

- “We Don’t Want to Just Study the World, We Want to Change It: Ethnic Studies and the Development of Transformative Students and Educators” By Kyle Beckham and Artnelson Concordia

- “Ethnic Studies and Community-Engaged Scholarship in Texas: The Weaving of a Broader ‘We'” By Emilio Zamora and Angela Valenzuela

- “For Us, by Us: Ethnic Studies as Self-Determination in Chicago” By Noem Corts, Jennie Garcia, Stacey Gibson, Dua’a Joudeh, Lupita Ramirez, Cecily Relucio Hensler, Cinthya Rodriguez, Maraliz Salgado, David Stovall, Johna Strong, Jessica Suarez Nieto, Aaron Talley, Lisa Vaughn, and Asif Wilson

- “Victory for Mexican American Studies in Arizona: An Interview with Curtis Acosta” Interview by Ari Bloomekatz

At a Seattle School Board meeting, students, teachers, and parents held signs reading “Teach Us Real History,” “Decolonize Seattle Public Schools,” and “Ethnic Studies Is the Truth.” In Portland, Oregon, students yelled, “Fists up, everyone!” and cheered as the Portland Public School Board passed a resolution in support of Ethnic Studies. Students descended on the California State Capitol in Sacramento to testify about how Ethnic Studies taught them about their histories and cultures and encouraged them to perform well in schools. In Providence, Rhode Island, student activists rallied for Ethnic Studies outside the Providence School Department, with one speaker proclaiming , “I deserve an education that makes me feel powerful.” In Texas, as the State Board of Education was considering the adoption of Ethnic Studies, student and community activists rallied with signs reading “We Are MAS [Mexican American Studies] Students, Hear Us Roar!”

On the heels of the banning of Ethnic Studies in Arizona in 2011 and atop a wave of California school districts making Ethnic Studies a graduation requirement, a movement has been unleashed in the United States. It is a powerful movement for K-12 Ethnic Studies that has sprung from students, teachers, and community activists seeking to transform curriculum and teaching into tools for social justice in public schools.

The Tucson Unified School District in Arizona is a touchpoint for K-12 Ethnic Studies. Although not the first to offer high school Ethnic Studies classes, Tucson Unified was the first to do so at a districtwide level with its Mexican American Studies program. Tucson’s Ethnic Studies program had a powerful impact on students that was documented by several studies: In Tucson’s schools, Mexican American Studies reversed the low-achievement/high-push out levels and general intellectual stagnation for Latinx/Chicanx students typically produced by the Eurocentric, standards-based curriculum and test-driven teaching of the past three decades.

In short, Latinx/Chicanx students who had seemed apathetic came alive through Ethnic Studies classes.

Teachers across the nation who had been teaching Ethnic Studies in their own classrooms already knew of its positive effects. Many teachers knew their textbooks fell far short of including Ethnic Studies knowledge. Many teachers viewed their purpose as not simply to raise students’ test scores but rather to equip students with the knowledge and experiences they would be able to use to improve conditions in their communities and their lives. These teachers knew from their own teaching that when students of color see their experiences, realities, histories, and intellectual frameworks represented in the classroom, they wake up and dive in.

In response to the progressive politics of the Ethnic Studies program, right-wing conservatives in Arizona viciously attacked the program and eventually banned Ethnic Studies in Arizona’s K-12 schools through state law HB 2281 in 2010. This law essentially outlawed Ethnic Studies for several years. The uproar it caused had a tremendous effect around the country, however, inadvertently launching what has become a national movement.

In a short period of time, the Ethnic Studies movement has spread like wildfire. Numerous school districts across California now require Ethnic Studies, and the state of California is in the beginning stages of developing model Ethnic Studies and Native American curricula. Oregon has a statewide requirement to develop and offer Ethnic Studies K-12, and in Kansas there are efforts to introduce statewide legislation. Indiana high schools will soon be required to offer Ethnic and Racial Studies as an elective course. States with large Indigenous populations—like Montana, Washington, and Alaska—have standards for including Indigenous knowledge in the curriculum. Seattle is in the process of implementing Ethnic Studies across the district; students in Providence, Rhode Island, have successfully lobbied for an Ethnic Studies pilot; and Albuquerque, New Mexico, is launching Ethnic Studies courses in all of its high schools. There are also individual Ethnic Studies courses popping up in individual schools around the country.

An Ethnic Studies Framework

The growing movement to bring Ethnic Studies into K-12 schools raises many important questions for teachers. What does Ethnic Studies mean and how should it be taught? Does Ethnic Studies mean teaching separate units about the cultures and histories of different ethnic groups? Does it have to be a separate class? Can one Ethnic Studies curriculum be developed, packaged, sold, and taught everywhere? Can anyone teach Ethnic Studies? If not, what kind of training and knowledge do Ethnic Studies teachers need? Is Ethnic Studies just for social studies or is it a way of envisioning and teaching the entire curriculum? Is Ethnic Studies the same as multicultural education or something else entirely? These are the kinds of questions we address in the pages of Rethinking Ethnic Studies.

Rethinking Ethnic Studies is organized around a holistic Ethnic Studies Framework that was initially proposed by co-editor and high school Ethnic Studies teacher R. Tolteka Cuauhtin. The framework connects directly with a review by co-editor Christine Sleeter on themes that run across the literature in African American, Latino, Asian American, and Native American Studies. Principles within this framework have been articulated by co-editor Miguel Zavala’s conceptualization of a rehumanizing and decolonizing pedagogy for Ethnic Studies, as well as co-editor Wayne Au’s ongoing work in anti-racist teaching and education for social justice. The framework is based on four basic premises:

1. All human beings have holistic, ancestral, precolonial roots upon our planet.

2. For many students of color, colonization, enslavement, and forced diaspora attempted to eliminate and replace their ancestral legacies with a Eurocentric, colonial model of themselves.

3. This Eurocentric, colonial model has been normalized for all students, translating to a superficial historical literacy and decontextualized relationship to history today and negatively impacting academic identity for students of color in particular.

4. In order for colonized students to initiate a process of regeneration, revitalization, restoration, and decolonization, they must honestly study this historical process as an act of empowerment and social justice.

Language and Ethnic Studies

We also need to address how language is used in this volume. Our language very often fails us. This book is written in English — a linguistic vestige of settler colonialism and white supremacy in the United States. It is the language of the “victors,” and it was used to carry out attempted cultural genocide. Our use of English carries this legacy with it. We recognize that when we use English to communicate, we are fundamentally bound by the politics of racism, patriarchy, sexism, capitalism, and colonization buried within the English language. Indeed, even when communicating in Spanish (which three of us also do), we are also using a Eurocentric language of colonization. Because Ethnic Studies is so strongly centered on anti-racism, cultural revitalization, and decolonization, it has always (and rightfully) struggled with the inherent contradiction of our use of the language of the colonization: Fundamentally we are trying to use what historically has been a tool for domination as a tool for resistance and liberation.

The word “ethnic” in Ethnic Studies symbolizes this contradiction perfectly. Although we currently use “ethnic” to refer to culture or a cultural group, the origin of the term is imbued with politics and power: Originally it meant “heathen” or “pagan”—both terms used to refer to non-Christian groups. More specifically, “ethnic” comes through the Latin and Greek ethnikos (heathen) to ethnos (nation), connoting a non-Christian (and, we might argue, non-Western) “other.” The politics of this should not be lost on us considering that “ethnic” is most often used to refer to non-white groups.

That said, Ethnic Studies is both about the critique of unequal power and the reclamation of power by marginalized and oppressed communities. In this way, the term “Ethnic Studies” itself is an example of one such reclamation. We’ve taken the word “ethnic” back, flipped the old meaning on its head, and are using it to build a movement that focuses on anti-racist and decolonizing curriculum and teaching. A term of oppression has been transformed into a term of potential liberation.

The chapters in Rethinking Ethnic Studies embody the overall struggle between Ethnic Studies and the English language in two ways. The first has to do with terminology. The English language categories for talking about race, culture, and gender are rigid, constrictive, and built on legacies of racism, patriarchy, sexism, and white supremacy. They are too inflexible to really describe our realities, especially if we want to name ourselves in ways that move beyond gender binaries and challenge the politics of race. In response to the confines of English, Ethnic Studies has pushed on the spellings and pronunciations of many commonly used racial and cultural categories and the gendered nature of the English language.

For instance, here in the pages of Rethinking Ethnic Studies, you will find a range of terms being used to identify the Indigenous and colonized peoples of the Americas (even the Italian roots of the term “America” communicate the political legacies of naming; Abya Yala, Turtle Island, and Ixachilan are three Indigenous names for the continent). While no Rethinking Ethnic Studies authors use the term “Hispanic” (which problematically means “of Spanish origin”), authors use “Latinx” or “Latin@” or “Latina/o” for peoples commonly referred to as Latin American. We see the limits in this terminology as well, given that the root of all these terms is “Latin”—thus based in a language of colonization, since Latinxs can actually be of any precolonial continental ancestry, which the term obscures. For these reasons, several authors also use “Chicana/o” or “Chicanx” or “Xicanx” to challenge gender binaries and to move closer to more Indigenous words, spellings, and identities.

Authors in this volume also try to challenge the gendered nature of several terms, including “history.” So you will see the term “herstory” used as a gendered counterpart, or even “hxrstory” (still pronounced herstory) as another step beyond the gender binary. Out of respect for the variety of terms and the politics and power of naming, we as editors of Rethinking Ethnic Studies have chosen to follow the lead of our contributors in how they’ve named many of these categories. This means that terms may shift from chapter to chapter.

In addition to new terminology, the second way the chapters here embody the struggle between Ethnic Studies and the English language is through the use of more academic and intellectual language. Ethnic Studies rests on the foundational understanding that education has been used for colonization and white supremacy, and as part of these processes, knowledge has either been kept from communities of color or offered up in safer, tamer forms that keep us from struggling for liberation.

So there is a tradition in Ethnic Studies of recognizing that those in power do not want us to know particular hxrstories, theories, politics, cultures, and forms of resistance; do not want us to be “smart”; do not want us to be intellectuals capable of thinking deeply about our existence. In response, Ethnic Studies has developed its own tradition of using academic and intellectual language as a point of resistance–a way to say, in the face of racism and white supremacy, “Yes, we are smart, and we have a right to understand the world in complex ways too.” As such, while Rethinking Ethnic Studies is not an academic text, it respects students and teachers enough to recognize that we can learn important and powerful concepts that can help us understand ourselves and the world.

Organization of the Book

Although Rethinking Ethnic Studies is not based on all the dimensions in the comprehensive Ethnic Studies Framework (see p. 65 for a more detailed discussion of the framework), elaborations of central elements are present throughout the volume.

Chapters in Part I, “Framing Ethnic Studies,” offer holistic conceptualizations of Ethnic Studies that connect curriculum, pedagogy, students, and community. Prior to the chapter that elaborates on the Ethnic Studies Framework that organizes Rethinking Ethnic Studies, chapters explain what Ethnic Studies is and is not, the centrality of students’ lives and student activism to Ethnic Studies, why Ethnic Studies matters for everyone, and what it means to teach Ethnic Studies. The four subsequent sections of the book are expressions of the four “macroscales” or “macrothemes” in the Ethnic Studies Framework.

Part II develops “Indigeneity and Roots”—the recognition of the sovereignty of the Indigenous nations on whose land teaching is taking place, as well as the identities, ancestral roots, and intergenerational legacies of students in the classroom. Chapters describe various strategies used by teachers from elementary through high school levels to help students explore their family backgrounds, in some cases opening up space to consider painful experiences of family members, such as having fled a war, having been enslaved, or having been forced to forget their ancestral family languages and stories. Chapters illustrate tapping into ancestral knowledge students may have learned at home or community members may hold and be willing to share.

Part III delves into “Colonization and Dehumanization”—the historic processes through which peoples of color have been robbed of land, labor, dignity, and autonomy. If students are to heal from the historic traumas of colonization and racism and learn to work for justice, they need to be able to understand oppressive relationships in historical terms. Chapters in this section take on issues such as genocide, segregation, institutional racism, and white supremacy, with some drawing connections to oppressive systems such as capitalism.

Part IV unmasks “Hegemony and Normalization”—the processes through which oppressive relations have come to be seen as normal or natural. Some chapters in this section critique and move beyond textbooks; others engage students in activities such as simulation and role play that are designed to prompt students to question “realities” they had previously taken for granted.

Part V addresses “Regeneration and Transformation”—the potential of working toward rehumanization and social justice activism. Chapters show multiple processes and concepts teachers have used to help students claim powerful identities of themselves as historically and culturally located people who are intellectually as well as politically capable of making a difference. Through combinations of hxstorical study, community study, role plays, and humanizing experiences in the classroom, young people learn to take on pressing issues in their own communities such as militarization of schooling and police violence.

The last section, Part VI, looks at the work of “Organizing for and Sustaining Ethnic Studies.” Here, authors from diverse parts of the country—ranging from San Francisco to Providence, from Chicago to Austin, from Sacramento to Portland—reflect upon their efforts alongside students and communities to advocate for and build Ethnic Studies programs. We envision this last section as an opportunity for organizers working for Ethnic Studies to learn from counterparts who have engaged in that work themselves. We envision this last section as an extension of the fourth macroscale, Transformational Resistance, and as an opportunity for organizers working for Ethnic Studies to learn from counterparts who have engaged in that work themselves.

Limitations of Rethinking Ethnic Studies

We recognize that there is a tension here: Our teaching is often contradictory in that we take part in designing lessons and developing units that are linear and exist within the standardization of public schools, yet we are also interested in being creative, engaging, and responsive, if not also liberating, in our teaching. Our hope is that our vision and orienting frameworks embrace a particular kind of “visionary pragmatism,” in the words of Patricia Hill-Collins, in which we keep our hearts in and our eyes on Ethnic Studies as a movement while also respecting the planning and carrying out of instruction that teachers must do within their specific contexts, institutions, and communities.