Zinn at 100: The Scourge of Nationalism

What Makes Our Nation Immune from the Normal Standards of Human Decency?

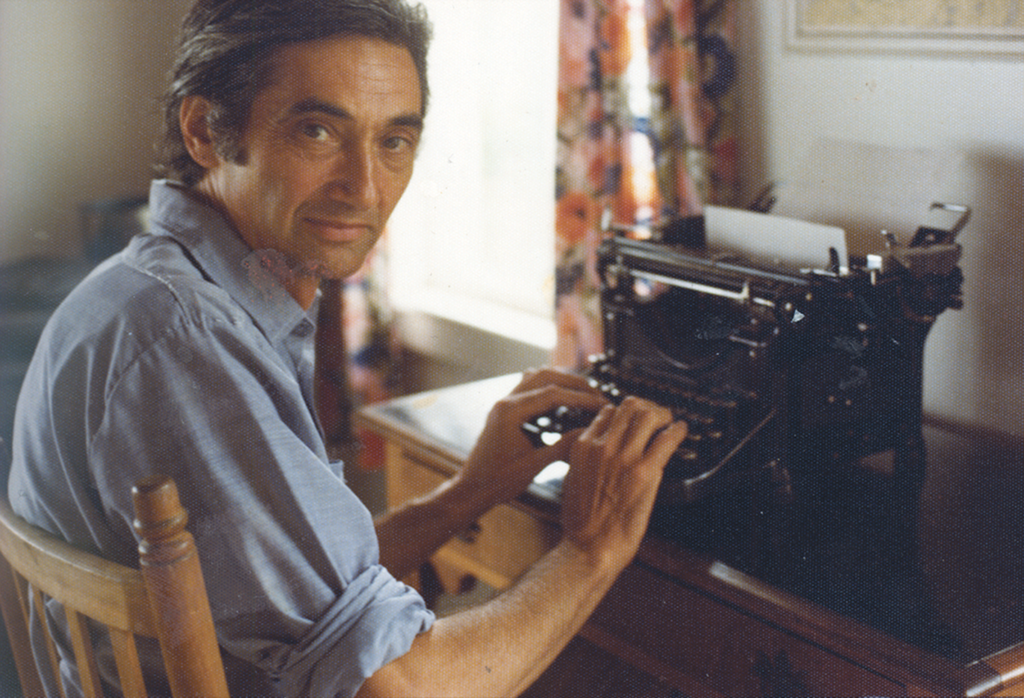

This year is the 100th anniversary of Howard Zinn’s birth. Zinn, who died in 2010 at 87, was a historian, professor, activist, and author of A People’s History of the United States, which has sold more than 4 million copies and is perhaps the most widely read U.S. history book. Through the years, Zinn granted interviews to Rethinking Schools, allowed us to reprint his writing, gave us kind blurbs for our books, and later collaborated with us and Teaching for Change to promote people’s history teaching by establishing the Zinn Education Project.

In honor of Zinn, we are featuring a “Zinn at 100” essay in each issue of Rethinking Schools this year. This is not nostalgia. We commemorate and celebrate Zinn for his ongoing relevance in helping us think about education and activism.

In her stirring 2018 preface to Zinn’s autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes:

There is no end to the list of horrors and atrocities that face us today and which many of us feel simultaneously overcome and angered by. Whether it is the awful continuation of police abuse and violence in Black and Brown communities or the vicious attacks on immigrant communities as dictated by American policies and law. In the face of these, and what feels like a million other challenges, it is all too easy to be pessimistic or cynical about the possibility of change and overwhelmed into doing nothing. Zinn’s lessons from history are never about names, dates, and the actions of this or that hero. Zinn’s focus was always on how the collective action of regular people — our neighbors, workmates, classmates, friends, family — was the most important ingredient in creating social change. . . .

We need Howard Zinn now more than ever. Not for the sake of romance or to construct another hero in history. We need his insights, his politics, and his commitment to the struggle for a better world. But he would be the first to tell you that he developed those insights from his intimate collaboration with hundreds of others. We no longer have him, but his words will live forever.

In this spirit, we offer some of those words in this issue.

— Rethinking Schools editors

***

The Scourge of Nationalism

What Makes Our Nation Immune from the Normal Standards of Human Decency

This article first appeared in The Progressive magazine in June 2005 (Vol. 69, Number 6).

I cannot get out of my mind the recent news photos of ordinary Americans sitting on chairs, guns on laps, standing unofficial guard on the Arizona border, to make sure no Mexicans cross over into the United States.

There was something horrifying in the realization that, in this 21st century of what we call “civilization,” we have carved up what we claim is one world into 200 artificially created entities we call “nations” and armed to apprehend or kill anyone who crosses a boundary. Is not nationalism — that devotion to a flag, an anthem, a boundary so fierce it engenders mass murder — one of the great evils of our time, along with racism, along with religious hatred?

These ways of thinking — cultivated, nurtured, indoctrinated from childhood on — have been useful to those in power, and deadly for those out of power. National spirit can be benign in a country that is small and lacking both in military power and a hunger for expansion (Switzerland, Norway, Costa Rica, and many more).

But in a nation like ours — huge, possessing thousands of weapons of mass destruction — what might have been harmless pride becomes an arrogant nationalism dangerous to others and to ourselves.

Our citizenry has been brought up to see our nation as different from others, an exception in the world, uniquely moral, expanding into other lands in order to bring civilization, liberty, democracy. That self-deception started early. When the first English settlers moved into Indian land in Massachusetts Bay and were resisted, the violence escalated into war with the Pequot Indians. The killing of Indians was seen as approved by God, the taking of land as commanded by the Bible.

Our citizenry has been brought up to see our nation as different from others, an exception in the world, uniquely moral, expanding into other lands in order to bring civilization, liberty, democracy.

The Puritans cited one of the Psalms, which says: “Ask of me, and I shall give thee, the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the Earth for thy possession.” When the English set fire to a Pequot village and massacred men, women, and children, the Puritan theologian Cotton Mather said: “It was supposed that no less than 600 Pequot souls were brought down to hell that day.” It was our “Manifest Destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence,” an American journalist declared on the eve of the Mexican War.

After the invasion of Mexico began, the New York Herald announced: “We believe it is a part of our destiny to civilize that beautiful country.” It was always supposedly for benign purposes that our country went to war.

We invaded Cuba in 1898 to liberate the Cubans, and went to war in the Philippines shortly after, as President McKinley put it, “to civilize and Christianize” the Filipino people. As our armies were committing massacres in the Philippines (at least 600,000 Filipinos died in a few years of conflict), Elihu Root, our secretary of war, was saying: “The American soldier is different from all other soldiers of all other countries since the war began. He is the advance guard of liberty and justice, of law and order, and of peace and happiness.”

Nationalism is given a special virulence when it is blessed by Providence.

Today we have a President [George W. Bush], invading two countries in four years, who believes he gets messages from God. Our culture is permeated by a Christian fundamentalism as poisonous as that of Cotton Mather. It permits the mass murder of “the other” with the same confidence as it accepts the death penalty for individuals convicted of crimes.

A Supreme Court justice, Antonin Scalia, told an audience at the University of Chicago Divinity School, speaking of capital punishment: “For the believing Christian, death is no big deal.”

How many times have we heard Bush and Rumsfeld talk to the troops in Iraq, victims themselves, but also perpetrators of the deaths of thousands of Iraqis, telling them that if they die, if they return without arms or legs, or blinded, it is for “liberty,” for “democracy”?

Nationalist super-patriotism is not confined to Republicans. When Richard Hofstadter analyzed American presidents in his book The American Political Tradition, he found that Democratic leaders as well as Republicans, liberals as well as conservatives, invaded other countries, sought to expand U.S. power across the globe. Liberal imperialists have been among the most fervent of expansionists, more effective in their claim to moral rectitude precisely because they are liberal on issues other than foreign policy.

Theodore Roosevelt, a lover of war, and an enthusiastic supporter of the war in Spain and the conquest of the Philippines, is still seen as a progressive because he supported certain domestic reforms and was concerned with the national environment. Indeed, he ran for president on the Progressive ticket in 1912. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, was the epitome of the liberal apologist for violent actions abroad. In April of 1914, he ordered the bombardment of the Mexican coast, and the occupation of the city of Vera Cruz, in retaliation for the arrest of several U.S. sailors.

He sent Marines into Haiti in 1915, killing thousands of Haitians who resisted, beginning a long military occupation of that tiny country. He sent Marines to occupy the Dominican Republic in 1916. And, after running in 1916 on a platform of peace, he brought the nation into the slaughter that was taking place in Europe in World War I, saying it was a war to “make the world safe for democracy.”

In our time, it was the liberal Bill Clinton who sent bombers over Baghdad as soon as he came into office, who first raised the specter of “weapons of mass destruction” as a justification for a series of bombing attacks on Iraq. Liberals today criticize George Bush’s unilateralism. But it was Clinton’s secretary of state, Madeleine Albright, who told the United Nations Security Council that the U.S. would act “multilaterally when we can, unilaterally when we must.”

One of the effects of nationalist thinking is a loss of a sense of proportion. The killing of 2,300 people at Pearl Harbor becomes the justification for killing 240,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The killing of 3,000 people on September 11 becomes the justification for killing tens of thousands of people in Afghanistan and Iraq.

What makes our nation immune from the normal standards of human decency?

Surely, we must renounce nationalism and all its symbols: its flags, its pledges of allegiance, its anthems, its insistence in song that God must single out America to be blessed. We need to assert our allegiance to the human race, and not to any one nation. We need to refute the idea that our nation is different from, morally superior to, the other imperial powers of world history.

The poets and artists among us seem to have a clearer understanding of the limits of nationalism. Langston Hughes (no wonder he was called before the Committee on Un-American Activities) addressed his country as follows:

You really haven’t been a virgin for so long

It’s ludicrous to keep up the pretext

You’ve slept with all the big powers

In military uniforms,

And you’ve taken the sweet life

Of all the little brown fellows . . .

Being one of the world’s big vampires,

Why don’t you come out and say so

Like Japan, and England, and France,

And all the other nymphomaniacs of power. . . .

Henry David Thoreau, provoked by the war in Mexico and the nationalist fervor it produced, wrote: “Nations! What are nations? . . . Like insects, they swarm. The historian strives in vain to make them memorable.”

In our time, Kurt Vonnegut (Cat’s Cradle) places nations among those unnatural abstractions he calls granfalloons, which he defines as “a proud and meaningless association of human beings.”

There have always been men and women in this country who have insisted that universal standards of decent human conduct apply to our nation as to others. That insistence continues today and reaches out to people all over the world. It lets them know, like the balloons sent over the countryside by the Paris Commune in 1871, that “our interests are the same.”