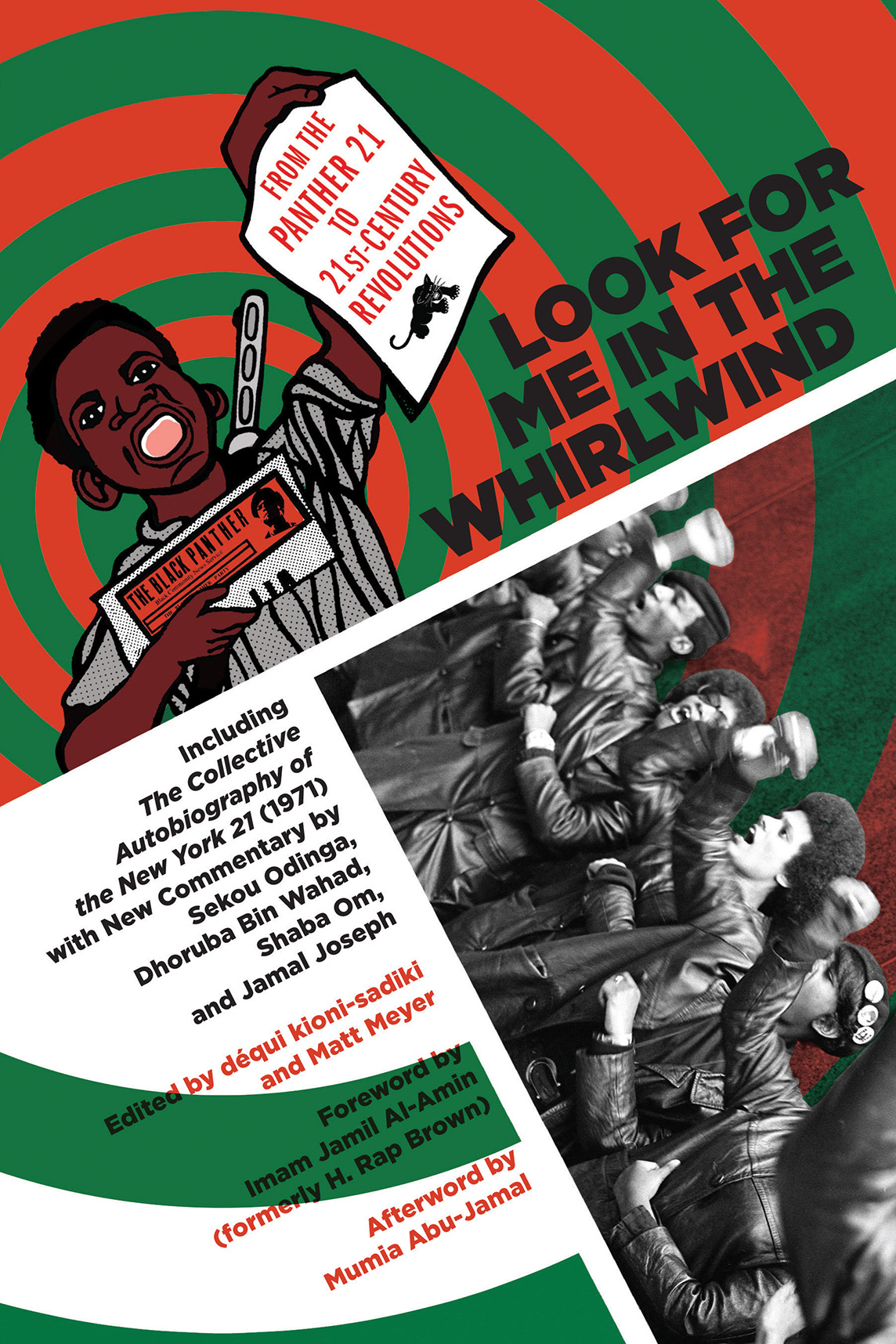

Why I Teach Look for Me in the Whirlwind

What makes Look for Me in the Whirlwind still current today is that a lot of the same political issues that existed then are relevant even now. As you go through the book and read the various sections, if you overlook the date you won’t be able to tell whether you’re reading about the 1960s or reading about today.

—Shaba Om, Look for Me in the Whirlwind

Shaba Om’s quote from the introduction summarizes why I teach the history of the Panther 21 using Look for Me in the Whirlwind: From the Panther 21 to 21st-Century Revolutions. While many histories of the Black Panther Party focus on the Oakland chapter, the New York chapter was one of the largest and most active. In an attempt to disrupt the rapid growth of Black Panther organization in 1969, the FBI and the New York City Police Department arrested and charged 21 New York Black Panther members with conspiracy to commit violent acts. The Panther 21 trial revealed illegal government activities and that police infiltrators had played key organizing roles and led to the acquittal of the 21 in 1971.

I teach an 11th- and 12th-grade honors level course titled Literature and Social Criticism at Columbia High School in Maplewood, New Jersey, a school with more than 2,000 students and a district that prides itself on diversity, but is not without challenges in serving students of color, particularly Black students. Teaching the Panther 21 enables me to address Black Power activists’ work as community organizers, their belief in self-defense (not random violence), and the illegal repression mounted by the U.S. government to “neutralize” them. I teach Black Panther history through literature to counter the “Good Civil Rights Movement” vs. “Bad Black Power Movement” narrative that still exists in too many classrooms: the Civil Rights Movement was good because it was nonviolent, and the Black Power Movement was bad because it supported violence. I seek resources that allow individuals to speak for themselves, without misleading interpretation.

The updated edition of Look for Me in the Whirlwind: From the Panther 21 to 21st-Century Revolutions is an excellent source of engaging essays, poetry, photographs, and literary representations by the New York Panther 21 and other revolutionary voices from the Black Freedom Movement. Like the original Look for Me in the Whirlwind published in 1971, the book includes the collective autobiography drawn from Panther 21 defendants’ personal reflections, broken up into 11 sections. The themes include family, community, education, Black culture, racism, and resistance. The entries range from a single paragraph to a couple of pages. The updated version includes new commentary by original Panther 21 defendants Sekou Odinga, Dhoruba Bin Wahad, Shaba Om, and Jamal Joseph. With a foreword by Imam Jalil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown), an afterword by Mumia Abu-Jamal, newly discovered or rarely seen Panther 21 poetry by Afeni Shakur and Sundiata Acoli, and past and present photos, the book provides a plethora of text and visual resources to use with students.

In my Literature and Social Criticism course, students and I engage with Look for Me in the Whirlwind through seminar discussions. First, I ask students to read and review the initial entry of all the defendants. After reviewing the entries, students choose three individuals they would like to follow throughout the reading. Then I assign each student one of their three choices. Students follow their assigned Panther 21 defendant throughout the biographical section of the book and explore that person’s reactions during class discussions. During the seminar, students present that person’s story in class with text quotes and analysis, discussion questions, and commentary about the connections they see between the past and present.

Look for Me in the Whirlwind exposes the impact of white supremacy on Panther members coming of age as young people in America, the experiences of interpersonal and institutional racism that ultimately led to their attempts to bring about social and political change in their communities. For example, Kwando Kinshasa writes about his coming to critical awareness while driving across the country with his father:

In 1955 I drove from New York to California with my father. My father made sure I saw the conditions of the red men who lived in the prisons that white people called reservations. . . . [P]eople pay admission to see other people struggling to live — all part of the tourist “see America” trip. I saw America all right. I saw a lot of hotels and motels we were not allowed to stay the night in. I saw racism in every state we passed through. I became painfully aware that somehow or other I had to learn more about what really goes down in this world.

By reading the autobiographical entries like Kinshasa’s, students learn that people are not born organizers, activists, and revolutionaries. Most often, they are ordinary people from hardworking families who develop a sociopolitical consciousness based on their experiences and interactions with others.

The Panther 21 reflections on their personal educational experiences deeply resonate with my students. Baba Sekou Odinga, who passed away this January, was a member of Malcolm X’s Organization of Afro-American Unity, and a founding member of the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party as well as the Black Panther International Section. In Part 3 of Look for Me in the Whirlwind, Odinga writes, “School was not a pleasant place for me. . . . I found most of the teachers to be a bunch of sadistic, pusillanimous, misunderstanding, unsympathetic, unprincipled jive motherfuckers toward children whose parents they considered to be from a totally different class.” When Odinga goes to live with his mother in Antigua at 12 years old, he has his first positive experience with a teacher. He recalls,

. . . my teacher was more than just “a teacher” — he was a humanistic teacher, a Black man who was concerned with the education of Black children, a teacher in the fullest sense of the word. His name was Mr. Lindsay. . . . Sometimes when we were reading something as a class he told us that some of the things in the books were not meant to educate us to the true value of our selves — that they were meant to give us a sense of inferiority.

My student, Maddy M, responded to Odinga’s entry:

This is oftentimes an issue when it comes to history textbooks. They always only tell one side of the story — often the white side. They paint these tragedies as white people saving POC or minorities when most of the time it is the opposite. The main issue is that these books are always written by white people who want to paint things in this way instead of by POC who can tell their side of the story or white people who are actually willing to put in the research and unbiased facts. However, I thought it was very good that Baba had a teacher reiterating how biased these books are and stressing how damaging they can be to the young mind. I feel like oftentimes, even in my experience, it is too often overlooked.

As a closing assignment I ask students to write on one of two topics: 1. Based on your reading, speculate what the “Panther 21” writer you followed might say to a group of young activists today, or 2. Write your own autobiographical essays discussing the challenges you face as organizers.

In the spirit of Shaba Om’s comments cited earlier, what makes the overall unit relevant is the degree to which students can take the lessons of the past and apply them to their own movements today. In my class, we connect the dots of a racist system that criminalized a generation of Black people addicted to drugs but declares an “opioid crisis” for the overwhelming number of white people addicted today; we look at the surveillance and repression of so-called “Black Identity Extremists” as a modern-day form of the FBI’s COINTELPRO seeking to discredit and disrupt the ongoing Black Freedom Movement. A vital teaching resource, the insights of the Panther 21 in Look for Me in the Whirlwind reverberate today.