Why I Don’t Teach the Hero’s Journey

When I was in 9th grade, Ms. Kleeg taught us The Odyssey, a timeless story about a boatful of guys who got lost in the Mediterranean for 20 years. I hated it. I remember the queasy feeling in my stomach as we took turns reading Homer’s epic poem of Ulysses’ long journey home and all of the wicked women who tried to bring him down. We learned about Circe, the femme fatale-style goddess who turned men into animals, the cruel sirens who lured good men to their deaths, and the worst in my view, the mealy-mouthed Penelope, too weak to say no to her suitors and too passive to do anything but sit in her bedroom weaving and unweaving all day.

Even though I probably couldn’t have articulated this thought at that age, deep down I knew that none of those females presented good options for me or modeled the adult I hoped to become.

Worse still, the story of the sailors forced to pass between the sea monster Scylla and the sucking whirlpool Charybdis was too dangerously close to my daily experience navigating the hallways of middle school in the late ’70s, trying to avoid the twin dangers of boys who made grabbing motions toward my breasts and the ones who called me a “dog” for wearing glasses. In class, it was the same boys who enjoyed the exploits of the brave Ulysses the most. When it was my turn to read, I would numbly recite my passage and go back to reading a copy of Pride and Prejudice hidden in my lap.

By the time my son lugged home a copy of The Odyssey in middle school, many teachers were framing it as a “hero’s journey.”

Based on the work of theologian Joseph Campbell, the hero’s journey curriculum highlights a common structural pattern present across narrative stories, myths, dramas, and religious rites. In a hero’s journey curriculum, students apply these patterns to literature in order to unmask the commonality or “monomyth” in all epic storytelling. According to Campbell, “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

The hero’s journey consists of 17 steps as the protagonist (always male in Campbell’s view) leaves the ordinary “feminine” world and ventures into the special world to re-emerge, transformed, back home. In Campbell’s view, the hero’s cycle and the character archetypes within it (the mentor, the villain, the trickster) supposedly exist deep in the human mind and evoke a profound response from the reader.

The hero’s journey has become a popular theory English teachers use to frame units around many novels, poems, and films. From The Odyssey to the first installment of the Star Wars series, students across the country identify and track the developmental stages of — face it — an almost always male protagonist as he navigates the stages of his hero’s journey.

I suppose I’m lucky to teach in a district that up until now hasn’t mandated teaching the hero’s journey, an approach that has always rubbed me the wrong way. I want all my students to not only recognize themselves in their reading, but also to learn about the world beyond, acknowledge their responsibilities to each other, and learn how to come together to shape the world that they live in. Because of its singular focus on the development of the individual, the hero’s journey does nothing to help our students progress toward the goal of becoming well-educated critical thinkers and thoughtful citizens of a democracy.

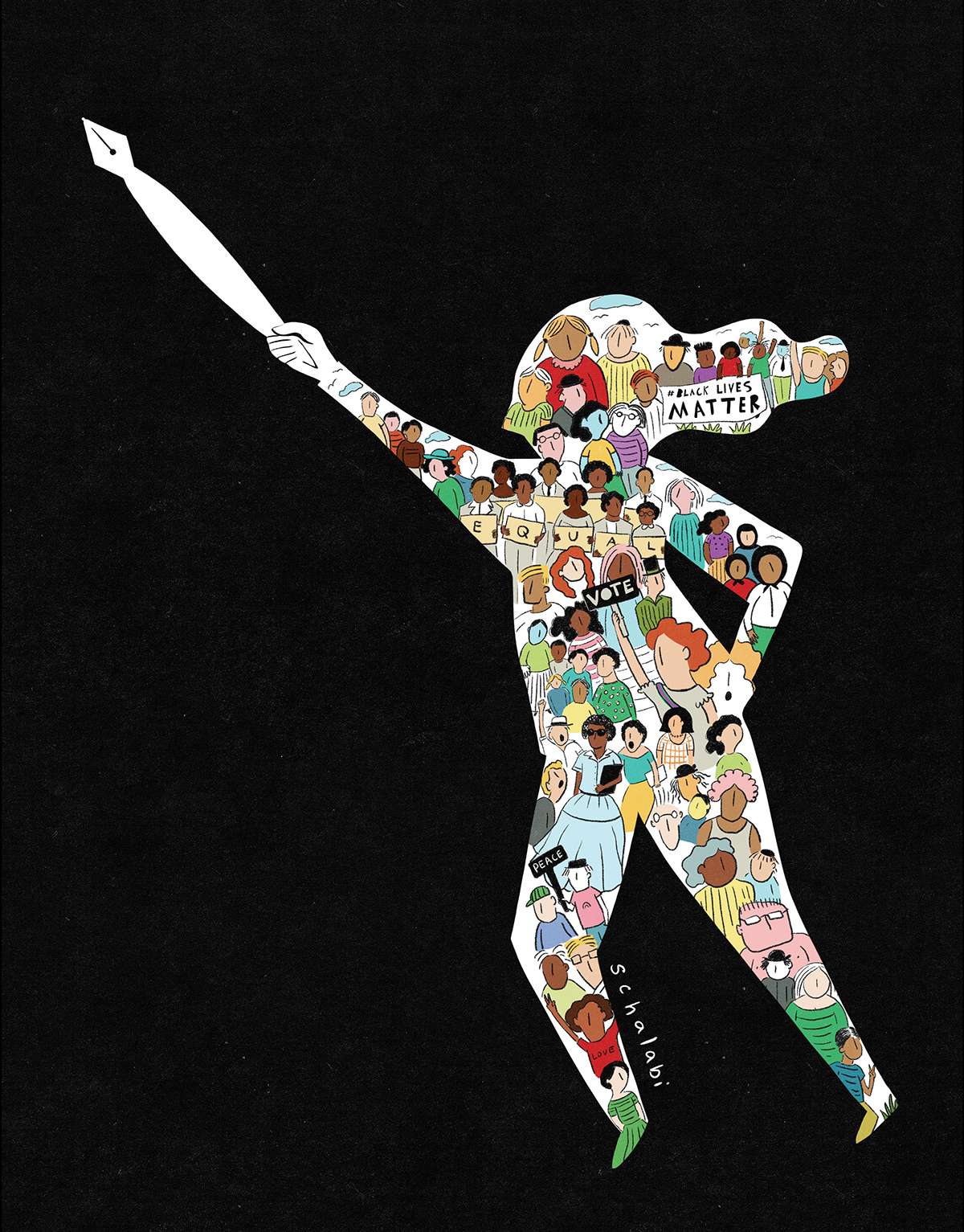

Events in the past few years make me wonder if it isn’t time for teachers to learn a few things from their students. All around the country, young people are coming together to organize for change. The student survivors of Parkland re-energized the national debate over gun control, the Black Lives Matter movement linked young people across the country together in the quest for racial justice, and others, like the 11th-grade students at Madison High School in Portland, where I taught for six years, came together en masse two years ago for an all-day sit-in to protest the sexual harassment of female students on campus. These young people understand the value of their collective efforts in standing up to the sexism of the status quo, a remarkable and ironic achievement given the relentless focus on the importance of the individual in so many of their English classes. Their success makes me question even more the extent to which our curricula — those sacred cows of the canon — help or hinder our students’ progress toward becoming well-educated critical thinkers and thoughtful citizens of a democracy.

In my classroom, I introduce readings that focus on the transformative effect of communities rather than individuals. In Warriors Don’t Cry, Melba Pattillo Beals’ memoir of the integration of Little Rock Central High School, I use activities that focus on the ability of groups to bring about significant social change. Before we even begin reading the book, I use Rethinking Schools editor Linda Christensen’s role play to re-enact the Little Rock school board’s decision to integrate the high schools. In this activity, students take on the role of community stakeholders debating the surprisingly nuanced pros and cons of school integration. Throughout the reading I focus students’ attention on the strength the Little Rock Nine drew every day from each other and the NAACP as they faced down racist hostility and violence both in and out of school.

I also teach Renée Watson’s This Side of Home, a novel about the collective efforts of a school community coming to grips with change. The African American protagonists, Maya and Nikki, live in a gentrifying neighborhood in North Portland. Their high school, previously a bastion of Black culture and history, replaces a Black history assembly with a watered-down “multicultural festival” that a diverse group of students organize against. Maya and Nikki’s individual goals and concerns are important and relatable to any teenager, but it is their efforts as part of a collective that bring maturity and growth in both their personalities and communities.

Young people need to know that meaningful social change comes about through social movements rather than the actions of the lone “heroic” individual they may learn about in traditional history classes. It was only through the work of committed groups that women in the United States gained the right to vote, and African Americans the right to equal employment opportunities, education, and housing — struggles that are still ongoing.

Although some of the students I teach have an instinctive grasp of this, young people still rely on their educators to frame curriculum in a way that acknowledges the power of the collective, instead of falling back on familiar approaches like the hero’s journey — a reactionary model that forces students to treat the (usually white, male) individual as the prime mover of life, the only one worthy of growth and change. This framework banishes other voices and other points of view to obscurity, and minimizes the importance of organizing for political and social justice.

In department meetings and other venues, teachers need to engage in critical conversations about the values imparted in curriculum if we really want to teach for equity and social justice and help our students become agents for change.