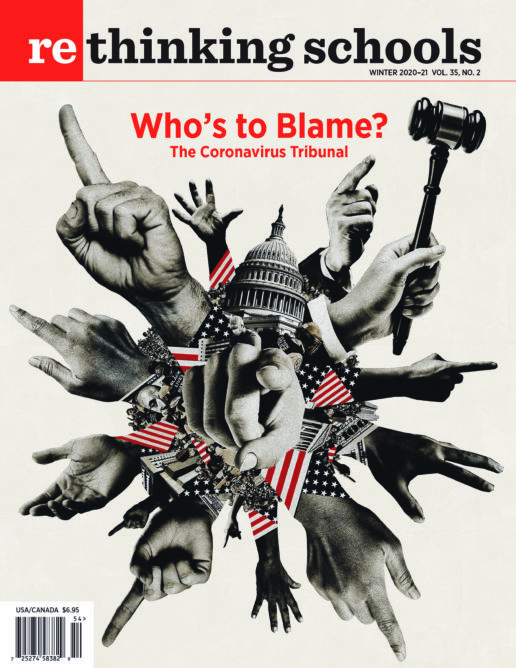

Who’s to Blame?

My Students Hold a People’s Tribunal on the Coronavirus Pandemic

Illustrator: Lincoln Agnew

By March 13, the last day of in-person classes in Washington, D.C., I had moved all desks in my classroom six feet apart and encouraged students to remain calm, use hand sanitizer, have empathy for other teachers and students, but to take precautions. It was clear to my students, who live in every region of the city and are overwhelmingly students of color, other teachers, and the entire staff at Hardy Middle School that the coronavirus, coupled with a lack of response or preparation, would change our lives for the unforeseeable future.

As my students and I entered spring break, President Donald Trump stated on March 19, “I would view [the coronavirus] as something that just surprised the whole world.” I knew this was false.

Based on updates from Italy, the U.K., and China, I knew the United States was unprepared. Capitalism, racism, and the U.S. government left us to die. Every day it became clearer to me that powerful elites in the United States were interested only in profit. The capitalist system in pandemic mode facilitated a lopsided transfer of wealth to the already-wealthy worth billions of dollars. But I, like most families, would receive only $1,200. And even this was up for debate. I kept watching other countries’ governments mobilize workers to clean cities or pass out masks; here, I had to find a way to buy my own personal protection. I would have a mask only if I bought one. I would have hand sanitizer only if I already had it. The U.S. government had no intention of ensuring that I was safe. Grocery store workers, truck drivers, day laborers, and others were called “essential,” but the government refused to pay them accordingly. The U.S. government said “thank you” in one breath and “work or starve” in the next. And then Dr. Fauci and other health experts began to highlight the exponentially more disastrous effect the coronavirus was having on Black communities. But most of this country’s leaders refused to admit that this was a direct result of inadequate health care and pre-existing conditions caused by institutionalized racism. And I knew my students were at home, left to process the information with their families, but not with a community. School was not serving its true purpose.

During the first few weeks of distance learning, my students completed projects on reparations for Native Americans based on Westward Expansion. Did the government owe anything to those forced to suffer American expansion? I knew my students were juxtaposing the past with the present. Millions of people were applying for unemployment, and yet the transfer of wealth to companies such as Amazon was clear. Did the government owe anything to those forced to suffer in the midst of a pandemic?

I originally planned to complete a culminating group discussion on the Indian Removal Act, using the Cherokee/Seminole Removal Role Play at the Zinn Education Project. But I also knew my students were being inundated with more articles, graphs, and research on the pandemic. Xenophobia was also on the rise as people across the country used racist language to describe the coronavirus. I wanted to do whatever my students wanted to do.

So I asked them.

I had students take a survey during the first week of April on whether we should talk in more detail about the Indian Removal Act or hold a tribunal on the coronavirus. Fifty-four out of the 60 students in class that day said let’s have a tribunal on who’s to blame for the crisis in the United States.

I chose to write a tribunal, rather than a mixer lesson or research-based activity, as the students had already mentioned that the tribunal on Columbus found in the Rethinking Schools book Rethinking Columbus was one of their favorite lessons of the school year. In addition, by March, I knew that my students’ generation was being blamed for something they were not responsible for — their own death and oppression. So I wanted to write a lesson to help them formulate their own language to fight back.

Students commented that information about the coronavirus was everywhere, and they felt overwhelmed. But were they overwhelmed with the same information? Was the information accurate? Was the information racist? I wanted to consider the fact that my students come from 13 different elementary schools and live in every ward in the District of Columbia. I could not just tell the story with different news items. I wanted to create a lesson to empower them to tell their story to me and to others. What did they know? What had they read? And how was it affecting their understanding of this crisis? What was wrong in society and how should we change it?

And that was the most important part of this lesson: students writing a 10-point program — inspired by the Black Panthers’ 10-point program, adopted in 1966 — on how to prevent crises like this in the future.

Support independent, progressive media and subscribe to Rethinking Schools at www.rethinkingschools.org/subscribe

Teaching the People’s Tribunal on the Coronavirus

This people’s tribunal begins with the premise that a heinous crime is being committed as tens of millions of people’s lives are in danger due to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus — COVID-19. But who — and/or what — was responsible for this crime? Who should be held accountable for the spread of the virus and its devastating impact?

Materials Needed

- Online conferencing tool (preferably one with breakout groups so students can work collaboratively on different pieces).

Time Required

- The time needed for this activity can vary considerably depending on the preparation and defenses mounted by students. Also, it is important not to rush through discussion of the activity as it is happening at a moment when students are worried, distressed, and angry. Their feelings are the same as adults and compounded by the fact that the major decisions in their lives about their future are determined by others.

Suggested Procedure

- In preparation for class, list the names of all the “defendants” on a slide: Mother Nature, Gen Z/Millennials, the Healthcare Industry, Racism, the Chinese Government, the U.S. Government, and the Capitalist System. I listed the names for my students in a PowerPoint slide.

- Tell students that each of these defendants is charged with murder — the murder of the hundreds of thousands and potentially millions of people in the United States. Tell them that, in groups, students will portray the defendants and that you, the teacher, will be the prosecutor.

- Explain the order of the activity:

• In their defendant groups, students will prepare a defense against the charges contained in the indictments. It’s a good idea for students to write these up, as they will present these verbally and may want to read a statement. (I initially planned for one day of research and indictment writing. However, students asked for two days to read the sources I provided and conduct their own research for the writing of their defense.)

• Before the trial begins, choose several students who will be sworn to neutrality. These people will be the jury. (I suggest choosing individuals to serve on the jury only after they have helped their groups write their defense.)

• As prosecutor, begin by arguing the guilt of a particular group.

• Those in the group accused by the prosecutor will then defend themselves and accuse one or more groups.

• The jury will then question the accused group, and others may also question the group and offer rebuttals.

• This process is repeated until all the groups have been accused and have defended themselves. The jury then decides guilt and innocence. - Ask students to count off into five groups of roughly equal numbers. Send each of the groups the appropriate “indictment” sheets. Remind students to read the indictment against them carefully and discuss possible arguments in their defense. Students may want to see the indictments against the other groups. Also, students may want to use other “evidence.” This could be an extension activity to discuss with them which evidence is trustworthy. I encourage initiating a larger discussion with them about how even normally reliable websites may also include inaccurate information. This will increase the time needed for the activity, and you may want to review the outside sources they use.

One rule: Members of a group may plead guilty if they wish, but they cannot claim sole responsibility; they must accuse at least one other defendant.

Students sometimes protest that it’s ridiculous to charge individuals for their own deaths — as in the case of the indictment of Gen Z/Millennials — or they may show some confusion about the “capitalist system” or “racism” as defendants. Tell them not to worry, that it’s your job as prosecutor to explain the charges. Many of my students wanted to accuse the system of capitalism, but wanted more information. I shared textbook and encyclopedia definitions of capitalism with them that we had read earlier in the year, and I also reminded them of videos we had watched on the profits of Amazon, harm to workers in Amazon factories, and Michael Moore’s film Capitalism: A Love Story, along with Matthew Desmond’s “American Capitalism Is Brutal,” a piece in the 1619 Project. - When each group appears ready, choose a jury — one member from each group (in a big class), or a total of three students in a smaller class. Publicly swear them to neutrality; they no longer represent the U.S. government, Gen Z/Millennials, or anyone else.

- The order of prosecution is up to you. I used Mother Nature, Gen Z/Millennials, the Chinese Government, the U.S. Government, and the Capitalist System. However, after completing the tribunal with my students, and consulting other teachers, I added the Healthcare Industry and Racism and White Supremacy. I save the Capitalist System for last as it’s the most difficult to prosecute, and depends on having heard the other groups’ presentations. As mentioned, the teacher argues the indictment for each group, the group defends, the jury questions, and other groups may then question. Then, the process repeats itself for each indictment. The written indictments should be an adequate outline for prosecution, but I feel free to embellish.

For example, many students questioned blaming Mother Nature for the exponential spread of the coronavirus during the tribunal. Specifically, they wondered why the Earth was being blamed for the choices humans were making not to physically distance themselves and wear masks. Students representing Gen-Z/Millennials responded by highlighting other natural disasters caused by Mother Nature, or they blamed the U.S. government. The students were clear in their judgment: Humans living in the United States, although they were not completely sure which ones, were responsible for the rising cases within the country. - On Zoom, each group presented their defense to the entire class. At the conclusion, I asked the jury to step out of the classroom and deliberate. On Zoom, I set up a separate breakout room for the jury so they could deliberate and return to the whole group once they reached a verdict. They also need to offer clear explanations for why they decided as they did. As the jury deliberates, I asked the rest of the class to step out of their roles and to do in writing the same thing the jury was doing. When I took a poll at the end of the first day of writing group defenses, an overwhelming majority — about 80 percent — asked for at least another day to review their writing.

Many groups asked me to look over their defense. From the beginning, it was clear that most blamed the U.S. government. Even the group defending the U.S. government wrote, “The United States government did not take action soon enough, therefore leading to the virus . . . spreading once it was in the U.S. We, the United States government, do take partial credit for the spread of the virus. . . . While Wuhan, China, was in the early stages of the coronavirus, they took no precautions to stop the virus from spreading. Since [the U.S. government has] known since December [2019] about this threat and didn’t [spread] the knowledge about how deadly the illness is, by doing nothing, they put more people at risk. The United States government was unprepared for a crisis like this since they didn’t take the virus seriously even after China sent warnings out.”

After deliberating, the jury sent a message to me via chat saying they reached a verdict. I brought them back to the whole group. When I asked about the verdict for both capitalism and the Chinese government, they responded “partially guilty.” This was interesting. Prior to joining the jury, it seemed to me that students thought that both the U.S. government and the Chinese government were guilty. But after listening to the defense presented by groups they changed their mind.

They knew the Chinese government built hospitals in days. They knew the Chinese government alerted the World Health Organization of the pending global pandemic. But they refused to not blame the Chinese government. They were willing to assign partial guilt to Mother Nature and capitalism. But in my students’ minds, the U.S. government was the main culprit. They said the U.S. government had time to prepare, but did nothing. This brought them back to earlier discussions in the class: They wanted time to discuss how to alter or abolish the government. But they had trouble separating the government from the economic system within which the government operates.

The aim, of course, was not to get students to come to a particular verdict, but to encourage them to try to make explanations for what is at the root of the devastation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, next time I will ask them to write more on the reasons for their verdict — both those exonerated and those guilty — so they are ready to articulate their reasoning when they announce the verdicts.

8. The jury returns and explains its verdict and then we discuss. Here are some questions and issues to raise:

• Was anyone entirely not guilty? (My students thought Gen Z was not responsible at all. They commented that older people always want to blame the young for their mistakes.)

• Did the prosecutor convince you that Gen Z/Millennials were in part responsible for their own deaths?

• Why do you think people are so quick to blame the young for the problems in society?

• How has racism impacted people’s understanding of the spread of the coronavirus in the United States?

• How would the spread of the coronavirus be different if the U.S. government had taken stronger measures in February of 2020?

• Describe how a national healthcare system would change the coronavirus pandemic in the United States.

• If the U.S. capitalist system is guilty, how can we change society or make a difference?

9. After students present their defense as a group, it is important to have a discussion and short writing or think-aloud reflection.

10. Finally, in small groups, give students the task of writing a 10-point program — a set of demands to address the problems we currently face due to this pandemic. (This, of course, is borrowed from the famous 10-point program of the Black Panther Party, in the 1960s.)

I told my students, “Tell me how we should change the United States. Remember, one of the key principles we discussed in the Declaration of Independence: If a government is corrupt, we the people have the right . . .” To which they responded out loud or in the chat, “to alter or abolish it.” And then I continued, “OK, if you believe the U.S. government is corrupt, how would you change it? How would you change society for the better? In your groups, try to decide on what we, the people, need. Immediate access to health care? More money from the government so we can stay home?” One student mentioned the need for free Wi-Fi since we are all using the internet. Others were concerned with the lack of access to groceries and basic necessities.

The point of this assignment was to not leave them simply with who or what was to blame for the coronavirus crisis, but for them to imagine the kind of society that could address the issues we had been discussing. Still, they struggled with writing a 10-point program. In hindsight, I should have given them several days to finish this piece. Their initial responses made it clear that they wanted a new system with guaranteed health care for coronavirus treatment. But they did not believe that the U.S. government would provide it. I wanted the final reflection to empower them to dream and create, but they were disenchanted. Creation takes time and a certain removal from the trauma they are facing, as well as more discussion. Most student groups did not create a completed 10-point program. But what they produced was thoughtful and important.

One student group wrote:

• All employees should receive paid leave for the time when a crisis strikes.

• If you go outside you should wear a face mask and gloves to leave the house.

• Free health care.

• Cancel international travel.

• Free coronavirus testing for all.

• Free Wi-Fi for distance learning.

• Food stamps weekly.

• Education of the virus so they know how to stop the spread.

And here are some of the suggestions of another student group:

• Start a committee in the United Nations specializing in pandemics to prepare if this situation occurs again.

• End, or lower the amount of, capitalism so no secrets are present and all the countries are aware of the situation.

• Build more factories to specialize in producing medical equipment.

• Increase the pay wage for nurses and medical professionals to reward them for their hard work and inspire others to become involved in the medical field.

• Normalize delivered groceries.

• Add a health check for passengers before boarding on any type of transportation.

Like most teachers, I was nervous about what would happen if I waited for 100 percent completion of the assignment. So, after a day and half I moved on. In hindsight, this was a mistake. Students wrote that they were enjoying the lesson and asked for more time, but the “teacher pressure” to keep going, over what my students needed, got to me.

Who knows what they would have written, changed, or suggested if each group had presented their suggestions to the class, as was my original idea. Who knows what my next groups of students will say after reading their peers’ suggestions.

The important thing I want to emphasize is that the aim of the lesson was not for students to arrive at some predetermined “correct” verdict and then some neat 10-point program to address the injustice of the coronavirus. What is essential is that students grapple with making explanations for profound social injustice. And that I offer them opportunities to imagine a profoundly different and better society. As a teacher, it was a joy to watch.

Coronavirus Tribunal Indictments

Note: These are abbreviated indictments used in the tribunal. For the full indictment roles, go to zinnedproject.org/materials/coronavirus-pandemic-tribunal

The Indictment: You are charged with the murder of hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of people in the United States, the disruption of lives, the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression, and unknown suffering.

Mother Nature

People call COVID-19 a war, and it is. It is a war waged by Mother Nature against human beings. Nature has created a virus that attacks human beings in the cruelest way imaginable — destroying their lungs, leading to unimaginable suffering. People are not doing this to each other: Mother Nature is doing this to people.

Gen Z/Millennials

You are the technology generation, and your lack of concern for others is putting everyone’s life in danger. “If I get corona, I get corona” is what you all touted proudly to the media during your 2020 spring break. You are unconcerned with how your decisions affect others.

Healthcare Industry

You are the insurance companies, for-profit hospitals, and pharmaceutical corporations that make up the so-called “healthcare system” in the United States. But rather than a system, what you have provided is deadly chaos — too few hospital beds and ventilators for COVID-19 patients, too few face masks and gowns to protect the nurses, doctors, and aides treating them, and you have state, city, and the national governments in a bidding war against each other for vital equipment.

Racism and White Supremacy

Unlike an industry or business, we cannot point to where you are located, except to say everywhere. In July 2020, the New York Times reported that throughout the United States, African Americans and Latinos are three times more likely to be infected with COVID-19 as whites, and almost twice as likely to die from the virus than white people. These statistics do not represent anything other than the health disparities that have plagued this nation for centuries. These policies are not just codified in law, they are everywhere, from the medical instruments used to test individuals for respiratory problems, to the way patients receive treatment. These disparities extend beyond access to a doctor, hospital, or prenatal care. Racism is in the structural fabric of this nation.

The Chinese Government

Let’s get this straight. This is not an indictment of Chinese people or Asian Americans. It is the Chinese government that is responsible for this crisis. In suppressing information about the virus, doing little to contain it, and allowing it to spread unchecked in the crucial early days and weeks, the Chinese government imperiled not only its own country and its own citizens, but also every person in the world.

The U.S. Government

From the very beginning, the president and entire government did not take the spread of the coronavirus seriously. In fact, they knew — both Democrats and Republicans — of the coming crisis. On Jan. 22, 2020, after China sent warnings and information to the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Donald Trump stated that “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. . . . It’s going to be just fine.”

The Capitalist System

Capitalism puts healthcare industry profits over human life. When this pandemic hit, 70 percent of low-income U.S. workers did not have any sick days — they had to come to work if they felt sick, even with coronavirus symptoms. If a low-wage worker chose not to come to work, they would be fired. They would lose their income and possibly be evicted from their apartment or home. That means tens of millions of people potentially spread the virus when they come to work even though they are sick.