Who Is Allowed to Teach Spanish in Our Public Schools?

Documenting the Consequences of the edTPA

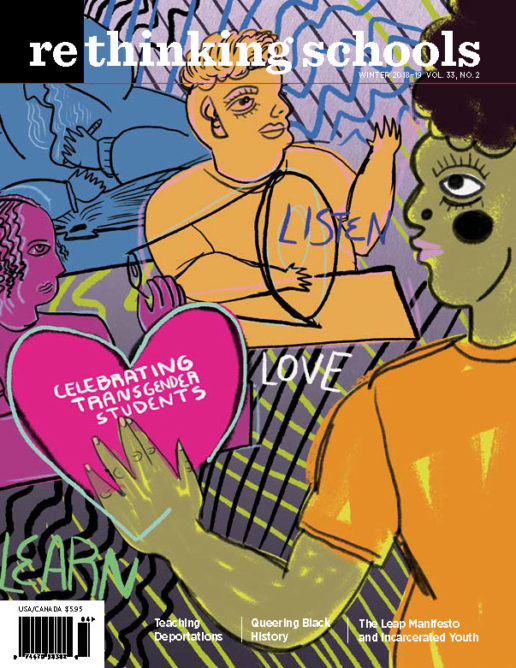

Illustrator: Rafael López

Maria (in July): Hello Professor, I took my edTPA and unfortunately

I did not pass by one point.

Prof. Jourdain (in July): Dear Maria, I am so sorry, especially to hear that

you were just missing 1 point! Maybe we could meet so I could help you

figure out which section(s) to work on. I’m sure that you will be able

to make the modifications necessary to pass the edTPA!

Maria (in August): Good morning Professor, Bad news. I don’t understand

why this time I got 31 and I fixed it and last time I got 34 . . . I gave it to a friend who is a teacher to read and see what I did wrong. I did what he suggested and I got less points than the first time. It’s very depressing. I wish I can fight this because it’s really not fair. Maybe I’m the one that doesn’t get it 🙁

Maria is a native Spanish speaker from Honduras who immigrated to the United States as a child and successfully completed a Spanish teacher preparation program. The teacher education faculty in her program noted that she would be “an excellent model for her students” and a cooperating teacher summarized her experiences with Maria by writing that she “possesses a high level of professional integrity.”

“She is reflective and inquisitive, and ultimately respectful of all she encounters here. The students respond positively to her. I would highly recommend her,” the teacher noted.

But Maria did not pass the edTPA.

Worse yet, when she made revisions and resubmitted her edTPA portfolio for re-evaluation, she received a lower score.

Maria found a position in a local private school, but she is still not eligible to teach in the New York state public school system even though her program’s teacher education faculty, as well as both of her cooperating teachers, were unanimous in deeming Maria qualified to begin her career as a Spanish teacher.

While Maria was disappointed, frustrated, and confused by her failures on the edTPA, another student in the program named Catherine was elated when she passed the edTPA on her first try. Catherine is a native English speaker from an upper-middle-class family who began learning Spanish in the 6th grade. She developed a fascination for the Spanish-speaking world and went on to major in Spanish in college, taught English in Chile for a year, then returned to complete a Master of Arts in Teaching Spanish and land her dream job as a high school Spanish teacher.

And take another student in the program, Roberto, a heritage Spanish speaker who grew up speaking Spanish and English at home — Spanish with his grandparents and his father, English with his mother and siblings. He majored in Spanish and Teacher Preparation, was a first-generation college graduate, and is now teaching middle school Spanish in a private Catholic school. Roberto has not submitted his edTPA because he is saving up to afford the fees. Like Maria, he cannot apply for teaching positions in the local public schools — unionized schools that offer much higher salaries and better benefits than most of the local private schools — because he has not passed all of the expensive and time-consuming state assessments of which the edTPA is a part.

Maria, Catherine, and Roberto all graduated from the same rigorous teacher preparation program. They all earned excellent grades and received praise from their teacher education faculty and their cooperating teachers who thought they were each ready to enter the profession. All three are creating the kinds of world language classrooms that we hope every child will be able to experience. They encourage their students to speak in Spanish about topics that are of deep personal interest and of relevance to their lives and their futures; they guide discussions around thought-provoking questions about perspectives held in other cultures; and they create vibrant classroom communities engaged with the world beyond the classroom walls — for example, giving students the opportunity to exchange letters and emails, or to Skype with their peers in a classroom in El Salvador, Peru, or Spain.

Yet unless some changes are made to teacher certification, it is unlikely that sufficient numbers of teachers like Maria and Roberto — native or heritage Spanish speakers — will be allowed to teach Spanish in our public schools.

By excluding native and heritage Spanish speakers, we further exacerbate the overall problem of racial disparity in our K-12 public school teaching force. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, more than half of the students in K-12 public schools are non-white, while 82 percent of their teachers are white. This is not to imply that white, native English speakers cannot be excellent Spanish teachers. They can be, and many are. The issue is that qualified native and heritage Spanish speakers are being excluded from the pool of potential public school teachers. Scholars such as Monzó and Rueda (2001) have noted the ways in which Latinx teachers’ knowledge of Latinx students’ language, interactional styles, and educational experiences can help them meet the academic needs of Latinx students. Indeed, the presence of Latinx teachers and paraeducators within the school community serves to foster greater understanding of Latinx students overall. In the field of world languages, native and heritage-speaking teachers additionally bring unique cultural and linguistic perspectives to the classroom.

What are some of the reasons behind the failure to get more teachers of varied backgrounds into our classrooms? One explanation centers on the artificial stumbling blocks being added to the teacher certification process in the name of “professionalization.” New York is one of 40 states that currently require, or are piloting, the edTPA, a performance assessment evaluation for teacher candidates. The edTPA is a portfolio of materials that teacher candidates submit to a private company (Pearson) for scoring. Materials include: three to five lesson plans constituting all or a portion of a coherent unit of instruction, with teacher candidate reflections on their planning; approximately 15 minutes’ worth of video showing the teacher candidate engaged in actual classroom teaching of a part of this unit, accompanied by academic reflections on the videotaped material; assessments administered to students during the unit, along with sample student work, and teacher candidate reflections on these; and a document in which the teacher candidate outlines the context in which the unit was taught — the specifics of the students, classroom, school, and district. All materials must be submitted according to strict and specific guidelines published in handbooks for each subject area created by SCALE (Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning, and Equity).

So who fails the edTPA? And why? Is it the candidates who do not display the professional preparation and qualifications that we desire in our teachers? One of the few large-scale studies to date evaluating the implementation of the edTPA, performed by Goldhaber, Cowen, and Theobald in 2016, found that Hispanic teacher candidates were more than three times more likely to fail the edTPA than non-Hispanic white candidates. This may be due to the difficulty of mastering the demands of the specific style of English writing required to pass the edTPA. For those preparing to become Spanish teachers, the edTPA requires the creation of lesson plans and teaching videos in Spanish, accompanied by extensive explanation in English of the work submitted. While I would like to be able to quote specific edTPA instructions from the world language edTPA handbook, everyone who helps to prepare candidates is required to sign a non-disclosure agreement that forbids distributing any of the material available in the edTPA. However, teacher candidate experiences suggest that to score well, the commentaries should demonstrate a style of academic reflection replete with what some call “educational jargon.” It is unclear to what extent any errors in written English may influence, consciously or unconsciously, the edTPA scorer. But should the ability to write grammatically perfect English in a specific style be the determining factor in whether someone is allowed to become a Spanish teacher?

Another stumbling block concerns the cost of certification requirements. In addition to the debt accrued by teacher candidates for college tuition and living expenses, these students must also pay large sums of money for state certification exams, licensing workshops, and fingerprinting. Costs in some states, like New York, can come close to $1,000. As part of these fees, teacher candidates pay $300 to a for-profit private company to submit their edTPA and have it scored. In New York, as in many other states, they must receive a passing score to obtain state certification. But candidates like Maria, who fail the edTPA, must pay again to repeat all, or a portion of, the assessment. The more candidates fail the edTPA, the more money the company makes. Yet it is often those who can least afford the certification expenses who are required to retake the assessment.

There are no publicly available data on the number of teacher candidates who are unable to complete their certification requirements, or are significantly slowed in their path toward certification, because they cannot afford the certification fees. We know that first-generation college students like Roberto generally face greater economic hurdles than other students. But should the ability to pay, and specifically the ability to pay a for-profit company for the privilege of submitting an assessment, be the determining factor in whether someone is allowed to become a Spanish teacher?

And in case you think this isn’t real, let me share some of the data from my institution’s world language teacher preparation programs. We are a large public research university in New York with world language teacher preparation programs, leading to New York certification in grades 7-12, in French, German, Italian, Russian, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Over one five-semester period, when the edTPA was first implemented in New York state as a high-stakes certification requirement in spring 2014, through spring 2016, we hosted 33 world language student teachers. All of these candidates successfully completed our rigorous programs, including successful student teaching placements. All of these candidates had GPAs of 3.0 or above, as required by our programs. All of these candidates were proficient in the languages they were preparing to teach. My colleagues and I, who had worked with these candidates for two years, determined that each was prepared to enter the world language teaching profession.

Of our 33 world language candidates, 20 were preparing to become certified to teach Spanish. Half were native or heritage Spanish speakers, half were native English speakers. During the period April 2014 to October 2016, nine of the 20 Spanish teacher candidates did not submit their edTPA portfolios to Pearson for evaluation. Five of these candidates were native or heritage Spanish speakers. In other words, 50 percent of our native/heritage Spanish-speaking candidates, and 40 percent of our native English-speaking candidates, did not submit their edTPA portfolios during or immediately after their student teaching semester. Some confided that they could not afford the expense, but they hoped to submit at a later date. Is it any wonder that we are facing shortages of world language teachers when as many as half of our qualified teacher candidates are not able to afford one of the newly imposed requirements?

The picture becomes even more disturbing when we examine passing rates on the edTPA among our candidates preparing to become Spanish teachers. Six of our native English speakers submitted their edTPA portfolios between April 2014 and October 2016. All six passed. Five of our native/heritage Spanish speakers submitted their edTPA portfolios during the same time period. Only one passed. All had received the same preparation. All performed well as student teachers according to their cooperating teachers and their university field supervisor. Yet of these 20 candidates, only one native/heritage Spanish speaker was eligible to receive New York state Spanish teacher certification during this time period while six native English-speaking students obtained certification.

Our case is probably not unique, but it is difficult to know because few other programs share their data. This is understandable. Let’s face it, who wants to announce that their candidates are failing? Our program has a robust number of Spanish teacher candidates, evenly split between native/heritage and non-native backgrounds. This situation brought to light an inequality that otherwise might have remained hidden.

And it is problematic that teacher preparation professionals have an ever-decreasing role in certification outcomes. Let us keep the valuable components of performance assessment that the edTPA promotes: All world language teacher candidates should create culturally rich, learner-centered lessons and assessments grounded in the best practices of the profession; they should videotape themselves teaching; and they should analyze and reflect on those lessons and assessments orally and in writing. But we should return all of these tasks, and their evaluation, to the teacher preparation programs. Let us fold performance assessment into the formative assessments that are part of the student teaching experience rather than outsourcing them to a for-profit company divorced from the actual preparation of teachers.

Who is allowed to teach Spanish in our public schools? Ironically, native and heritage Spanish speakers are being kept out of public school classrooms designed to celebrate their own language and cultures, while white, privileged native English-speaking teachers are welcomed in, creating a two-tiered system that smacks of racism and elitism. All of our children deserve opportunities to learn Spanish from excellent teachers like Maria and Roberto — native speakers, heritage speakers, teachers of color.

References

Goldhaber, Dan, Cowan, James, and Roddy Theobald. 2016. Evaluating Prospective Teachers: Testing the Predictive Validity of the edTPA. National Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research. Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED573246

Monzó, Lilia, and Robert Rueda. 2001. “Professional Roles, Caring, and Scaffolds: Latino Teachers’ and Paraeducators’ Interactions with Latino Students.” American Journal of Education, 109(4), 438-471.

National Center for Education Statistics. 2017. Digest of Education Statistics. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_203.50.asp