Who Can Stay Here?

Documentation and citizenship in children’s literature

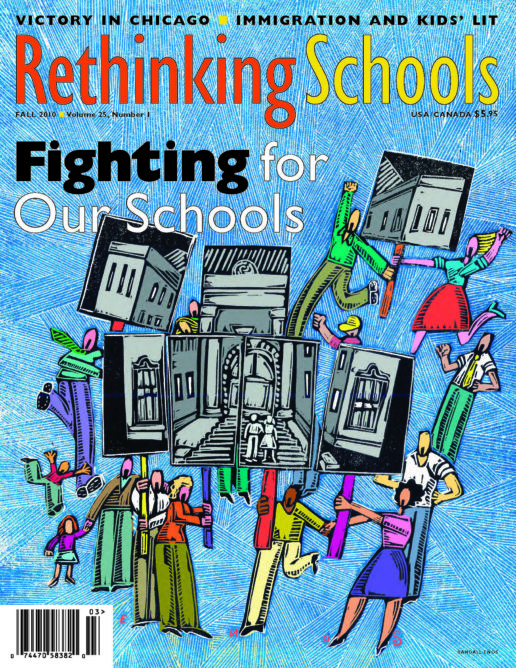

Illustrator: Richard Downs

Nearly three years ago, the bilingual elementary school where I taught in East Oakland was subject to an attempted U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raid. Rumors began to fly early in the school day among students and teachers—ICE agents had been seen parked several blocks away from the school. The campus went into a panic, terrified that the agents would apprehend parents on their way to pick their children up from school. Office staff and parent volunteers called each family at home, instructing them to send only documented friends or relatives to get their children at the end of the day. The administration contacted the press. Soon, Mayor Ron Dellums and members of the Oakland police force were gathered outside, denouncing the fear tactics being used by ICE.

While politicians made statements outside, it was my job inside to calm down a class of 1st graders who were all too aware of what an ICE raid meant. They knew their parents could be taken away or that they themselves could be forced to suddenly leave the familiarity of their homes and schools. As my students were playing outside during recess, a news helicopter began to circle above the playground. Half of my class came running back inside, panicked, hysterical, in tears, saying that la migra was coming in helicopters to get them. It was almost impossible to assuage that fear—to tell them that they were safe here and no one would take them away. Especially because I didn’t really know if that was true.

The ICE agents never actually entered our school that day. Perhaps this was because intimidation had been their only goal, or perhaps the barrage of media attention put them off. However, I later learned that several other schools in East Oakland and South Berkeley were subject to similar intimidation tactics that day—ICE agents parked nearby, watching and waiting for parents and students to leave the campus. At one East Oakland elementary school, a mother was apprehended by ICE agents in the school hallway before the start of classes. She was led away in front of her 6-year-old daughter and gathered parents and staff.

Though such a dramatic brush with immigration enforcement didn’t reoccur during the two years that I worked at that school, each year many teachers, myself included, were asked by parents to write letters on their behalf for immigration hearings. And each year I knew of at least one student whose mother or father was deported.

So when I set about compiling a list of children’s picture books that deal with immigration issues, the memories of that attempted ICE raid and the deportation hearings were fresh in my mind. I found books that dealt with many themes: intergenerational ties and gaps, peer pressure and friendship, and, of course, language barriers and language learning.

What caught my attention was one theme that was missing. Though many of these books dealt with border crossings, very few addressed issues of documentation and unequal access to citizenship in any meaningful way. Indeed, most skirted around the topic, leaving unexplained holes in their narratives of immigration. Others explicitly sent the message that citizenship in this country is equally attainable by all—a fact that many of my students clearly know to be false from their own life experiences.

It is understandable that children’s book authors are reticent to address such controversial and political issues in their books, especially in the current climate. Taking a strong stance on undocumented immigration and unequal access to citizenship could limit their audience. Many might consider the issues involved—deportation, the separation of families, economic and racial discrimination—too frightening or “adult” for the children who will read their books. Yet when I think about my students’ fear on the day that ICE came near our school, I can’t escape the realization that many of our children deal with these issues on a daily basis. These powerful experiences and fears make their way into students’ school lives, whether we want them to or not.

When we create immigration units or read picture books about immigration to our children, I do not believe we have the luxury to avoid these topics. Indeed, I believe that if we do we risk marginalizing the students who cannot choose to ignore these issues in their daily lives. Of course, children should never be prompted to share sensitive personal information or disclose their immigration status, but these topics can be discussed safely through a literary lens. If we want to provide literature that helps children understand their world better and realize that they are not alone in the ways they feel and the problems they face, it is important to critically analyze children’s books about immigration. What kinds of messages do they send to students about documentation and access to citizenship?

With all of this in mind, I identified three broad categories of books according to the extent to which they explore or obscure these themes. Here are a few examples to illustrate each category. I hope that this provides a framework for critical analysis of children’s literature about immigration and is helpful to teachers planning curriculum or adding to their classroom libraries.

Creating the Image that Citizenship Is Equally Available to All

The first category comprises books that choose to ignore issues of undocumented immigration and unequal access to citizenship, portraying a world in which U.S. citizenship is equally (and often easily) available to all people. The most extreme example of this that I encountered is A Very Important Day, by Maggie Rugg Herold, in which families from the Philippines, Mexico, India, Russia, Greece, Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, China, Egypt, Ghana, Scotland, and El Salvador all joyously celebrate as they make the trip downtown to the courthouse to receive their papers and to be granted citizenship. They happily swear loyalty to the United States of America and recite the Pledge of Allegiance, waving tiny American flags as they exit the courthouse.

This book strongly implies that each family has had an equal opportunity to apply for citizenship, whether from Scotland or Ghana. They have all followed the same equitable legal process that is described in the epilogue. For a child unfamiliar with the economic, linguistic, and political issues that make U.S. citizenship far more attainable for some than others, this book creates a false sense of security—look, our system is working well! For a student who is undocumented or whose parents are undocumented, this book raises many unanswered questions—why can’t we just go down to the courthouse, recite the Pledge of Allegiance, and become citizens if everyone else can? Unless a teacher is willing to engage with these issues and discuss the author’s underlying assumptions with the students, this book could do more harm than good in a classroom setting.

The second book in this category, How Many Days to America? A Thanksgiving Story, by Eve Bunting, does portray immigration and border crossings as difficult, but the barriers suddenly and inexplicably disappear in the end when the need arises to create a happy ending. This book tells the wrenching story of a family that is forced to leave an unnamed Latin American country, fleeing from political oppression. They board a fishing boat to travel to the United States. Their journey is arduous—the motor breaks, the soldiers in their country shoot at them from the shore, their food and water run out, people become ill, and what little they have left is taken by thieves. When they finally arrive at the shore of the United States, they are greeted by soldiers who give them food and water but do not let them land. “They will not take us,” the father comments sadly, but he refuses to explain why.

Yet suddenly, the next day, the boat makes landfall on U.S. shore again. This time there are no soldiers, but instead a large crowd of people who welcome the family and usher them into a shed with tables covered with delicious food. They explain that it is Thanksgiving and tell the new arrivals about the significance of that day in the United States. The book ends with a description of how “Father gave thanks that we were free, and safe- and here.” The little sister asks if they can stay. “Yes, small one,” the father replies. “We can stay.”

This book clearly sets up a false expectation: No matter the struggle that it takes to get to the United States, once here, you are safe and you are allowed to stay. Yet this is so clearly not the case for many undocumented immigrants, and many children recognize that, despite their family’s arduous journeys to this country, they still face the dangers of deportation, exploitation, and discrimination on U.S. soil. Just as this book stays silent on the reasons why the soldiers initially refuse to allow the family to land, it all too swiftly conjures up a happy ending when many questions still remain in the mind of a critical reader. Like A Very Important Day, it ignores the possibility that citizenship might not be attainable for all people who set foot on U.S. shores.

Someone Else’s Problem

If the first category is comprised of books that ignore issues of documentation and equitable access to citizenship completely, the second category includes books that hint at these themes but do not explore them. They imply that the aforementioned dangers exist, yet avoid putting the main characters at any real risk. The message that they send is that deportation and the separation of families does occur, but that such things usually happen to someone else.

The first of these books, My Diary from Here to There/Mi diario de aquí hasta allá, by Amada Irma Pérez, is the diary of a girl who immigrates to the United States from Mexico. Although her father is a U.S. citizen, the family must wait a long time near the border while her father secures their green cards. The narrator expresses sadness at how she cannot see her father and fear that he will not be able to get green cards for the rest of the family. Yet they wait patiently, the green cards finally arrive, and the family is able to cross the border legally and be reunited. Interestingly, on the bus into the United States, the police arrest a woman without papers. This incident is mentioned but not discussed, leaving children on their own to question why some immigrants have documents and others do not.

Another book, the charming Super Cilantro Girl/La superniña de cilantro, by Juan Felipe Herrera, tells the story of Esmeralda, a child whose mother is stopped at the U.S.-Mexico border despite the fact that she is a U.S. citizen. Worried about her mother, Esmeralda dreams that she turns green like a bunch of cilantro, grows into a giant, and flies to the border to set her mother free. Here Herrera paints a vivid picture:

She gawks at the great gray walls of wire and steel between the United States and Mexico. She stares at the great gray building that keeps people in who want to move on.

In the dream, Esmeralda rescues her mother. When the soldiers begin chasing her, she makes green vines and bushes of cilantro grow up and erase that border, declaring that the world should be sin fronteras—borderless. However, when Esmeralda wakes up in the morning, she discovers that everything was a dream and that her mother is already safely back home.

This book hints at the terror that children experience at the prospect of their families being split apart, but it does not actually put the characters in real danger. Esmeralda’s mother is a citizen and does not truly run the risk of being separated from her family. In the foreword, Herrera expresses concern about families that are kept apart by borders and shares his wish that some superhero could abolish such borders and bring those families back together. However, his choice to make Esmeralda’s mother a citizen in no danger of actually being barred from returning home still sends the message that family separation, deportation, and detention centers are all part of a dream from which you can wake up. If they are real dangers, they exist only in the lives of others.

Tackling the Subject

The final category includes the handful of books I found that do deal with issues of documentation and unequal access to citizenship head on. In Hannah Is My Name, by Belle Yang, a family immigrates to San Francisco from Taiwan. Though they apply for green cards, they wait more than a year to hear back from the government. During this time, the narrator’s parents must work illegally to make ends meet. Hannah’s mother is fired from her job in a clothing factory when the boss realizes that she doesn’t have papers, and her father is constantly on the watch for immigration agents as he works at a hotel. One of Hannah’s friends, Janie, a child from Hong Kong, is deported because Janie’s father is discovered working at a Chinese restaurant before his family receives their green cards. And one day, while Hannah is visiting her father’s work, she and her father are forced to flee from an immigration raid. From then on, her father must work at night. In the end, the story concludes happily—the family finally receives the green cards and is allowed to stay. In the process, however, the author exposes several key issues, including the seemingly arbitrary nature of the immigration process (e.g., papers can be delayed for extended periods of time without explanation) and the fact that many families must work illegally to survive while applying for documents.

América Is Her Name/La llaman América, by Luis J. Rodríguez, deals with many other harsh issues facing immigrant communities: neighborhood violence, unemployment, language barriers, and, importantly, racism, an issue that is not directly addressed in any of the books reviewed above. América’s mother is called a “wetback” when she goes to the market. In school, América’s ESL teacher, Ms. Gable, scornfully refers to her as an “illegal.” América’s confusion is heartbreaking:

How could that be—how can anyone be illegal! She is Mixteco, an ancient tribe that was here before the Spanish, before the blue-eyed, even before this government that now calls her “illegal.” How can a girl called América not belong in America?

This is a powerful question to pose to students, one that could generate much discussion. Fortunately, América finds release from the pressures of her life through writing poetry, discovering her voice and her place in this new passion. Her family and her teacher, who are initially skeptical, finally support her, telling her that she will be a real poet some day. “A real poet,” the book concludes. “That sounds good to the Mixteca girl, who some people say doesn’t belong here. A poet, América knows, belongs everywhere.”

Teaching Critical Thought

The books critiqued above are only a few of the many that are available. However, although there are many children’s books that deal with the experiences of Asian and Latin American (specifically Mexican) immigrants, there is a paucity of literature that tells the stories of immigrants from other places in the world, such as Africa or the Middle East. I urge teachers to seek out books that do represent these populations when building their classroom libraries, especially books that choose to tackle the difficult issues surrounding immigration status and citizenship. This is especially important if we want immigrant students to recognize that they are not the only ones who face struggles in the United States—that many different groups share similar experiences and that this may in turn be due to the existence of larger systemic injustices.

I have reflected on the books above from the perspective of a teacher whose class includes immigrant students, many of whom are undocumented or have undocumented family members. However, I believe that it is just as important for teachers who do not have immigrant students to look critically at the books about immigration available in their classrooms. In all probability, children who do not confront these issues in their daily lives are the least likely to question the portrayals of immigration in the books they read.

Finally, and most importantly, I want to emphasize that none of these books stands alone, regardless of whether they choose to confront or evade the topics of documentation and inequitable access to citizenship. Read these books aloud and make them the subject of group discussions before adding titles to the classroom library for independent reading. This is to assure that the sensitive issues involved can be treated with care, given the attention they deserve, and dealt with in a safe environment mediated by a caring adult. If our goal is to develop students who think critically about their own lives and about the world around them, teachers should be integrally involved in guiding children as they discover, explore, and analyze all of these books. I have tried to provide a framework to help us, as educators, look closely at the messages sent by the books about immigration that we choose for our classrooms. Thinking critically about the books ourselves is the first step in facilitating thoughtful dialogue among our students.

| From North to South/Del norte al sur By René Colato Laínez Children’s Book Press, 2010 Hot off the press, From North to South/Del norte al sur addresses issues of family separation and deportation head-on. The story is told from the perspective of José, a young child who travels from San Diego to Tijuana to see his mother, recently deported in a factory raid. At the shelter where she is staying, José meets other women and children who have also been separated from their families. It is clear how deeply his mother’s deportation affects José—and this is movingly described—but there are several reasons that his situation should not be considered broadly representative. His father is a permanent resident of the United States and can hire a lawyer for his mother, and José lives close enough to the border to visit her every weekend. His mother has been able to find lodging at a safe and welcoming shelter, and every indication is that she will soon be able to return home. Neither the other women and children in this book, nor our own students who face similar challenges, are guaranteed these advantages and resources. Thus there is much here for teachers to discuss with their students—especially the complex reasons behind José’s family’s separation and the different ways that families experience deportation. The story ends with a description of José’s dream as he sleeps on the car ride back to San Diego: mamá has the right papers, the family crosses the border together, fireworks fill the sky, and José knows “that all the other children would see their parents soon, too.” This is a beautiful dream, but it is indeed a dream. The real world does not deliver fairytale endings so reliably, and the other children at the shelter may not soon be reunited with their families. In this respect, the book seems torn between the attempt to realistically portray the pain caused to children by deportation and the desire to provide a happy ending. In choosing the latter, it may set students up with the unrealistic expectation that deportation is always temporary, and those who face it will inevitably be reunited with their families in the United States. Despite these issues, From North to South/Del norte al sur remains one of the only children’s books that directly portrays a child’s struggle with family separation caused by deportation, and so is an invaluable addition to any classroom. —G. C. |

REFERENCES

Bunting, Eve. How Many Days to America? A Thanksgiving Story. New York: Clarion, 1988.

Herold, Maggie Rugg. A Very Important Day. New York: Morrow Junior Books, 1995.

Herrera, Juan Felipe. Super Cilantro Girl/La superniña de cilantro. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, 2003.

Pérez, Amada Irma. My Diary from Here to There/Mi diario de aquí hasta allá. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press, 2002.

Rodríguez, Luis J. América Is Her Name. Willimantic, Conn.: Curbstone Press, 1997.

Rodríguez, Luis J. La llaman América. Willimantic, Conn.: Curbstone Press, 1998.

Yang, Belle. Hannah Is My Name. Cambridge, Mass.: Candlewick Press, 2004.