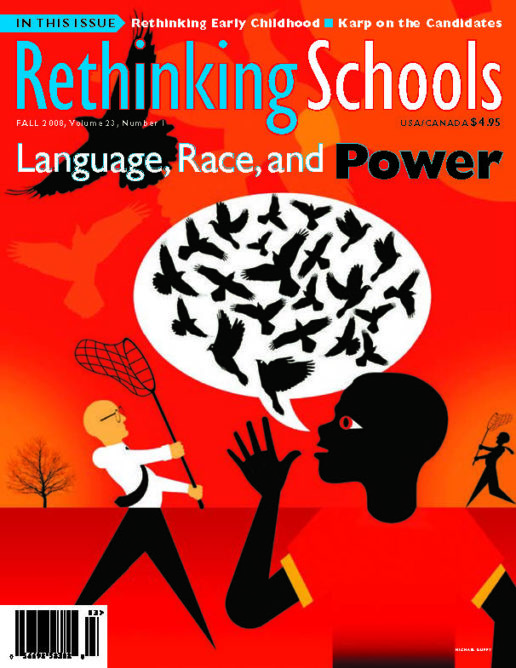

Preview of Article:

Which of the Above?

The '08 election: another high-stakes standardized test

Illustrator: Randall Enos

Presidential elections are like bad multiple choice tests. There are no perfect answers and the best choice usually comes from the process of elimination.

True, this year’s test seems relatively easy. Only a very slow learner could still doubt what the Republicans are offering: an endless “war on terror;” unregulated corporate greed; and relentless attacks on social programs, the environment, and what’s left of the Bill of Rights. If you liked George Bush, John McCain’s your man.

As for the Democrats, Barack Obama should probably be on the ballot twice: once as the charismatic new leader whose call for “change we can believe in” just might resonate with enough voters to elect the first African American president and stretch the boundaries of U.S. politics, and once as the latest Democratic nominee whose centrist balancing act might not survive the cash-driven media circus that passes for electoral democracy in the United States.

While a Democratic victory is no guarantee of substantive change (see the 2006 congressional elections), after nearly eight years of Bush and No Child Left Behind, there’s no denying how shifts in presidential administrations can have major impact on public education at every level.