Preview of Article:

When Emma Goldman Entered the Room

Dealing with the unexpected in a role play

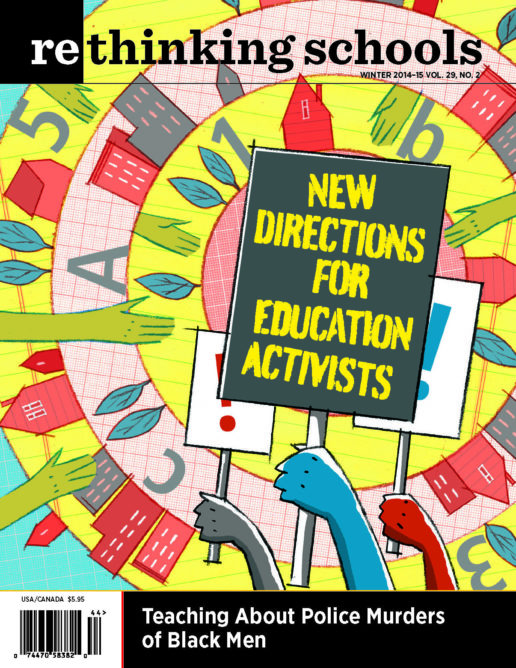

Illustrator: Ethan Heitner

The room was awhirl: students dashing in and out, noisily planning strategy, silently reviewing questions, rehearsing their speeches. Most were already in costume—making adjustments to headbands, scarves, ties, and jackets—when José arrived. He was a football player, 6 feet tall, dressed in women’s clothes complete with makeup, an ample bosom, a smile on his face, and an accentuated swish of the hips. His entrance was greeted with laughter, whispering, and catcalls, especially from the female students. He walked the length of the room as though it were a catwalk, hips swinging and eyelashes batting.

Ignoring José, I called my students together, had them take their places as character teams in a large circle, and began to introduce our role play. The unit was thematic and focused on the fears and political sacrifices of the 1920s, 1950s, and 2000s. In all three time periods, there was something feared. These fears were exaggerated and exploited by those in power. During the 1920s, it was the Russian Revolution and communism; during the ’50s it was communism, Stalin, and the atomic bomb; and during the 2000s, Islamic terrorism. The effects of these exploited fears included the increased surveillance of U.S. citizens, the rollback of fundamental rights and freedoms, and racist attacks and expulsions (even of citizens). I asked students to use the essential question “What are we willing to sacrifice to feel safe?” to compare the three time periods in order to put the use of torture, the prison at Guantanamo Bay, extraordinary rendition, and the U.S. Patriot Act in historical context. Students examined primary source documents, including letters, speeches, and newspaper articles; read excerpts from several secondary history sources; watched film of Joe McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee; and analyzed excerpts of the 9/11 Commission report.

I then assigned teams of students to roles from the three time periods (e.g., ACLU founder Roger Baldwin, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., President Woodrow Wilson, Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, President Harry S. Truman, blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow, Sen. Russ Feingold, and President George W. Bush). From their historical figure’s perspective, students wrote speeches, developed questions, and framed an argument to answer the essential question. José and his team represented Emma Goldman—anarchist, free speech advocate, feminist, and all-around rabble-rouser.

José spoke for his team during the opening of the seminar portion of the role play. He was third up and followed strong and well-rehearsed speeches delivered in the characters of Baldwin and Holmes. As I introduced Goldman, José strode to the middle of the room. The giggles and catcalls re-emerged. He stood center stage, cleared his throat, and re-adjusted his fake breasts, to the complete delight of the crowd. He began speaking in a forced, fake, and high-pitched voice, continuing his comic charade. The voice distracted everyone at first, especially when he began to work the room, walking back and forth, pointing at different historical characters in the room, gesticulating to emphasize his points.

However, his arguments as Emma Goldman were spot on, well thought out, detailed, and complete, with several well-placed quotations from Goldman herself: “No real social change has ever been brought about without a revolution . . . revolution is but thought carried into action.” “The demand for equal rights in every vocation of life is just and fair.” “The history of progress is written in the blood of men and women who have dared to espouse an unpopular cause.” Some were from speeches we’d analyzed in class, others were from the group’s own research. As Goldman, José asked several rhetorical questions: “What and who are we afraid of? Who says we should fear them? What’s the source of the information?” He argued that the fear was misplaced: “The world is made of workers who are oppressed and exploited. Through this we are all united.” He finished his speech with a crescendoed call to action and resistance that Goldman herself might well have been proud of. His bow was greeted with thunderous applause.

The role play continued. Other speakers delivered such strong performances that the project engaged us for three full days.

Role plays and other forms of experiential learning always carry a risk. There is an emotionality to them and a stretching of oneself that generally garners strong academic and intellectual results, but can also carry students to places that surprise them, and sometimes surprise me, too. Taking on a role allows students to move beyond themselves; this can include women as male characters, men as females, Latina/os as whites, African Americans as Native Americans, and so on. Although it is not necessary, I find that having students dress in character in some way, from something as small as making a nametag to creating a full-on costume, can help them find the voice and nuance of their person. I give students the choice of playing either the character or someone who was close to and supportive of the character’s positions. This allows everyone to participate at their own comfort level.