Preview of Article:

When 21st-Century Schooling Just Isn’t Good Enough: A Modest Proposal

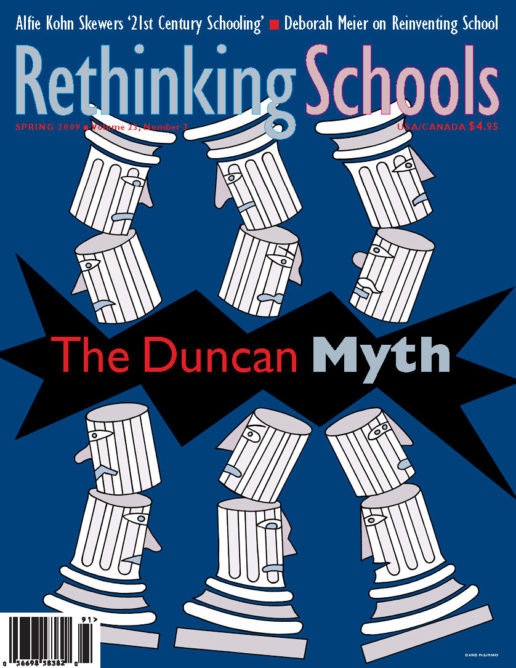

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

Many educators, and even more people who aren’t educators but are kind enough to offer their advice about how our field can be improved, have emphasized the need for “21st-century schools” that teach “21st-century skills.” But is this really enough, particularly now that our adversaries (in other words, people who live in other countries) may be thinking along the same lines? Unfortunately, no. Beginning immediately, therefore, we must begin to implement 22nd-century education.

What does that phrase mean? How can we possibly know what skills will be needed so far in the future? Such challenges from skeptics—the same kind of people who ask annoying questions about other cutting-edge ideas, including “brain-based” education—are to be expected. But if we’re confident enough to describe what education should be like throughout the 21st century—that is, what will be needed over the next 90 years or so—it’s not much of a stretch to reach a few decades beyond that.

Essentially, we can take whatever objectives or teaching strategies we happen to favor and, merely by attaching a label that designates a future time period, endow them (and ourselves) with an aura of novelty and significance. Better yet, we instantly define our critics as impediments to progress. If this trick works for the adjective “21st-century,” imagine the payoff from ratcheting it up by a hundred years.

To describe schooling as 22nd-century, however, does suggest a somewhat specific agenda. First, it signifies an emphasis on competitiveness. Even those who talk about 21st-century schools invariably follow that phrase with a reference to “the need to compete in a global economy.” The goal isn’t excellence, in other words; it’s victory. Education is first and foremost about being first and foremost. Therefore, we might as well trump the 21st-century folks by peering even further into the future.