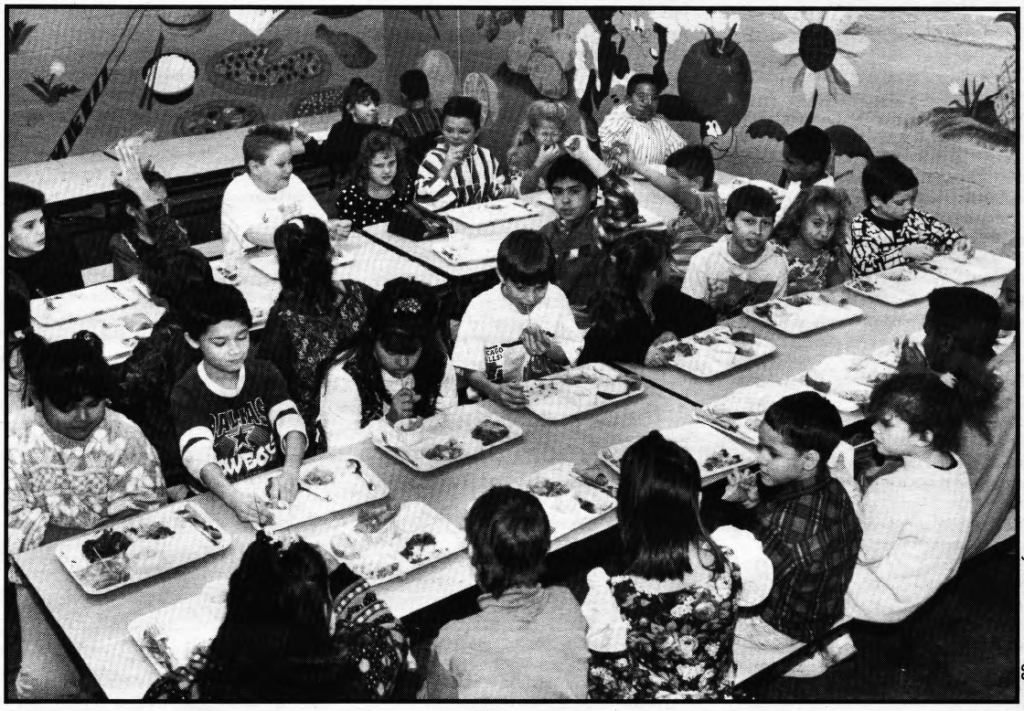

What’s for Lunch?

Meal Program Threatened by Republican Agenda

Illustrator: Susan Linsa Ruggles

When Congress passed child nutrition legislation this October, it made the most significant changes in the school lunch program since it began in 1946. Most important, new regulations call for schools participating in the federal meal program to significantly cut the fat and salt content of the food they serve by the 1996-97 school year.

The new regulations are overwhelmingly seen as a qualitative step in improving the nutritional quality of the 25 million lunches and 5 million breakfasts served daily under the federal school meal program. But the optimism that accompanied passage of the Better Nutrition and Health For Children Act was tempered by shortcomings that allow corporate and agricultural interests to maintain policies at odds with nutritional quality and health.

For example, the dairy lobby successfully fought to preserve the status quo in serving whole milk to school children, and the soft-drink industry helped defeat language that would have strengthened controls on vending machine sales. The legislation also failed to regulate the nutritional content of the fast foods that are increasingly being offered in school cafeterias by companies such as Taco Bell and Burger King.

These legislative shortcomings, however, are nothing compared to the threat posed by the November elections. Republican leaders such as incoming House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) are promising to balance the budget, cut taxes, and increase military spending — which means that social programs are all on the block. Advocates of improved school nutrition policies fear that the coming years could be a re-run of the Reagan era, when the president proposed that ketchup be considered a vegetable and the school lunch program was cut by almost $1 billion. In fact, the school lunch program has never fully recovered from the Reagan presidency, and participation in the school lunch program is still 2 million less than it was in 1979 before the budget cuts.

“It is completely unknown what will happen with the bill, because of the election, because of the budget, the deficit, the fiscal situation,” Kevin Dando, a spokesperson for the American School Food Service Association, told Rethinking Schools.

In an ominous development, House Republicans drafted a proposal in late November calling for a lump sum to be allocated to each state for 10 nutrition programs, including the federal meal program. Under current policy, the programs automatically expand depending on need, and anyone who qualifies receives the benefit. The proposal, which the Republicans plan to introduce in Congress this January, also calls for an immediate 5% cut in the money available for the nutrition programs.

Such an approach “would be a nightmare,” notes Mary Kelly, administrator of school nutrition services for the Milwaukee Public Schools. “Draconian would be the only way to describe it.”

History of the Program

Federal involvement in school lunches began primarily to serve agricultural interests, not the nutrition of children. That legacy still affects the school meal program, and explains why it is under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and not the U.S. Public Health Department or the U.S. Department of Education.

The first federal involvement in child nutrition was during the Depression in 1932 when Washington began donating surplus agricultural commodities to schools. “Although feeding children at school was supported, it was largely incidental to farm and job relief efforts,” according to an historical overview by the House Committee on Education and Labor.

Nutritional concerns were wedded to this broader focus when U.S. officials became alarmed during World War II because nearly half of the men drafted had physical disabilities related to childhood malnutrition or tooth loss. The school lunch program was authorized in 1946 as a matter “of national security” to “safeguard the health and well-being of the nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other foods.”

In 1966 the school breakfast program was added. Although the breakfast program has never been as widely available as the lunch program, efforts have been made in recent years to strengthen the breakfast program. Under both the breakfast and lunch programs, free or reduced-price lunches are provided to those meeting low-income requirements.

In the almost 50 years since the federal government began the school meal program, the country’s health problems have changed dramatically. Malnutrition, while still a problem, has been overtaken by poor nutrition, in particular obesity and overconsumption of salt, sugar, and fat, and by lack of exercise. Over half of all deaths in this country are now due to cardiovascular diseases — diseases directly related to food and exercise. In contrast, the major cause of premature mortality at the beginning of the century was infectious diseases such as scarlet fever, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and measles.

Dr. James Moller, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Minnesota and immediate past president of the American Heart Association, views the school breakfast and lunch programs as an essential component of child nutrition, and thus a necessary area of concern for teachers, parents, and child advocates.

“There are millions of kids who are getting their major source of nutrition from the schools,” he said. “And whether the schools like it or not, they are providing the bulk of a child’s diet.”

Moller applauds the new regulations, which require that the amount of fat in school food programs be reduced from what is now roughly 38-39% of the calories, to approximately 30%.

The new guidelines are important for two reasons, Moller told Rethinking Schools. “First, there is clear evidence that arteriosclerosis begins in childhood and that there is more of it in children who have a high blood cholesterol level, which is determined mainly by the food they eat. Second, you’d like children to develop eating habits they will use throughout life. It’s hard to grow up eating McDonald’s hamburgers and fries and then when you are 18, to suddenly stop.”

While awareness of the importance of good nutrition and exercise appears to be on the rise, the number of overweight adults and children is skyrocketing. The American Heart Association estimates that between 6 and 15 million children are obese — an increase of 39% in 12-to 17-year-olds since the 1960s, and 54% in 6-to 11-year-olds.

For adults, the number of overweight people jumped by a third from 1980 to 1990, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Roughly 33% of all adults are now considered overweight.

“The proportion of the population that is obese is incredible,” Dr. F. Xavier Pi-Sunyer wrote in an editorial this summer in the Journal of the American Medical Association. “If this was about tuberculosis, it would be called an epidemic.”

Legislative Controversies

One of the easiest ways to immediately improve the nutritional quality of the school meal program and to reduce the fat content would be to eliminate the serving of whole milk, which gets half its calories from fat. But the dairy lobby has consistently opposed such a step, and once again won the day during the congressional debate on the bill this fall.

Using a Catch-22 type logic, Congress said schools shall continue to offer students a variety of milk consistent with “prior year preferences,” unless the preference for any type of milk is less than 1%. Thus, schools can only stop serving whole milk if less than 1% of the milk served the year before was whole milk.

Julie Rabinovitz, nutrition policy coordinator for the Public Voice for Food and Health Policy in Washington, D.C., said the requirement means schools will have limited ability to reduce the consumption of whole milk.

“Schools only buy as much as the kids drink,” she told Rethinking Schools. “So whatever they purchased this year is set in stone for the next year. And what is served next year is set in stone for the following year.”

The dairy lobby defends whole milk because dairies pay farmers based on the milk’s fat level; the higher the fat, the more the farmers make. But there must also be a market for high-fat milk — which is where the schools come in.

Vending Machine Sales

Another area of controversy involved sales from vending machines. Sen. Pat Leahy (D-Vt.) had originally hoped to strengthen a federal regulation that prohibits the sale of soft drinks and foods with minimal nutritional value in the cafeteria during lunch time. Nutrition advocates argue the language is filled with loopholes. For example, a vending machine in the cafeteria can sell chocolate, which has calcium and thus is not considered of minimal nutritional value, or a school can locate a machine with soda one foot outside the cafeteria door.

Some nutrition advocates had argued that soft drinks and junk foods be banned entirely in the schools, at least during school hours. But corporate lobbyists prevailed and the bill was watered down. The matter largely was left for local schools and school boards to resolve — where pressure is intense to allow vending machines because school organizations get a cut of the money.

“All it [the legislation] does is put the schools on notice that they can do something about junk food, but it doesn’t itself take any positive steps,” John Gleason, of the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington, D.C., told Rethinking Schools.

The soft drink industry was up-front about the reasons for opposing a stronger measure. “We make no nutritional claims for soft drinks, but they can be part of a balanced diet,” Randal Donaldson, a Coca-Cola spokesman, was quoted as saying. “Our strategy is ubiquity. We want to put soft drinks within arm’s reach of desire. We strive to make soft drinks widely available, and schools are one channel we want to make them available in.”

Leahy, meanwhile, responded: “As chairman of the Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee, I have stood on the Senate floor and defended child-nutrition programs hundreds of times. I have fended off attacks from drug companies, petty crooks, price fixers, budget cutters and critics of all kinds. I never thought I would see the day that I would have to defend our child-nutrition programs under heavy attack from the Coca-Cola company, one of America’s corporate giants, with worldwide profits of $2.1 billion last year.”

The legislation also failed to curb nutritional abuses by fast food companies, which view the country’s schools as “the last great marketing frontier,” as Gleason of the Center for Science in the Public Interest put it.

Gleason said he applauded the new guidelines on regulating fat and sodium in school lunches. But no such guidelines apply to fast foods served in school cafeterias.

“My biggest problem with the bill is that it does nothing to improve the nutritional quality of competitive foods,” Gleason said.

“The bill has no provisions requiring that a la carte lines, which sell Taco Bell or Pizza Hut, meet the same nutritional standards as the school lunch program. This is a huge, gaping problem. At a time when fast food is taking over the schools’ cafeterias, there are no nutritional requirements on fast foods.” A number of child nutrition advocates have long advocated universal free lunches in the schools, and the legislation this fall authorized $9 million per year for pilot programs to test the feasibility and cost of universal free lunch. Advocates of a universal free lunch make three main arguments: it is sound educational and nutritional policy; it will reduce the stigma attached to those receiving free or reduced lunches; and it will significantly reduce paperwork.

“The whole idea behind universal [free lunch] is to endorse the concept that every child in this nation has a right to a nutritious meal at school,” argues Mary Kelly, head of food services for the Milwaukee Public Schools. “You don’t want to have a perception that the lunch program is only for poor kids. It’s a nutrition program. And if you embrace the notion that good school nutrition has a positive relationship to education, then all students will benefit.”

Such arguments hold little sway with budget-conscious congresspeople, however. Universal pilots were not even called such, but were known as the “reduced paperwork and application requirements and increased participation pilots.”

In choosing such a bureaucratic title, legislators were trying to appeal to anti-bureaucracy sentiment — which, as any teacher will testify, is a valid concern when it comes to the school lunch program.

The bureaucracy is particularly noticeable in elementary grades, where classroom teachers collect the money and then send an envelope to the food service manager saying how many kids will eat a free lunch, how many a reduced, how many will pay, and how many will purchase additional milk. Then the food service manager takes the envelopes, does a tally, distributes appropriate tickets back to the classroom teacher, who must hand them out before lunch — and hope the kids don’t lose them and cause another round of bureaucracy. In the cafeteria, the kids hand in their tickets, which are later sorted once again based on free, reduced, or paid. Then the food manager must fill out a final report based on each category.

Add the paperwork necessary to determine who is eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, and the school meal program becomes a nightmare of red tape. In fact, The National Center for Education Statistics has estimated that more than 40% of all the reporting burden in public schools comes from the school lunch program.

“In the past four years, more than 300 schools have dropped the [meal] program, affecting tens of thousands of students,” according to Dando of the American School Food Service Association. “And one of the major reasons is the staggering amount of paperwork to make sure, God forbid, that we don’t give a free meal to a kid who is ineligible.”

Dando also notes that a stigma is often attached to receiving a free or reduced lunch despite efforts by teachers and schools to reduce such problems. “Wherever students are receiving free and reduced price meals, that’s where the stigma is, whether it’s Oklahoma or New Jersey, urban or rural.”

Whether the universal pilots will ever happen is another question, however. The $9 million per year for the program was merely authorized — which means there is permission to ask for the money but no guarantee it will be appropriated during the federal budget process next year. Given the boldness of the right wing in attacking even acclaimed social programs such as Head Start, child nutrition programs could easily be sacrificed for the sake of completing the Reagan revolution.

In coming months, it will be essential that advocates for improved school nutrition follow the federal budget and “watch for any proposed cuts in child nutrition programs,” Dando cautioned. “It’s important to keep an ear to Washington, to keep oneself educated and vigilant.”