What We Learned from Our “Oakland to Gaza” K–12 Teach-In

More than 20 U.S. educator unions have passed resolutions calling for a cease-fire in Gaza, some going as far as to label Israel an apartheid state and an occupying force. National Education Association President Becky Pringle issued a personal statement in support of a cease-fire. Our own union, the Oakland Education Association (OEA), also passed a resolution at our Nov. 4 Representative Council calling for an immediate cease-fire and an end to the Israeli occupation and encouraging union members to show their support by attending marches, contacting elected officials, and teaching about Palestine.

After the resolution passed by almost a two-thirds margin, a group of rank-and-file organizers (of which we are a part), involving educators of all grade levels, formed OEA for Palestine to consider next steps. It was clear to us that educators must offer more than official union statements. We must encourage our co-workers and students to think deeply about the humanitarian crises unfolding in the world and the role of the United States and others in creating and sustaining them.

Over about a month of regular meetings, a core group of 10 grew to a network of 50 teachers, and generated the idea of organizing a teach-in. Knowing that our ability to navigate complex issues with our students is one of educators’ greatest strengths, we reasoned that educators could organize a teach-in to apply our labor toward encouraging critical discussion and global political consciousness. Oakland teachers had begun teaching about Palestine long before the teach-in. Oakland educators and students were already participating in marches and protests for a cease-fire. We hoped the teach-in could bring the energy of this activism into our classrooms and encourage more interest in the movement.

OEA has a history of supporting districtwide teach-ins, including a 1999 teach-in about the political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal and the death penalty, one in 2003 about the war on Iraq, and in 2011 about state-imposed austerity measures in education. After extended debate centering around whether a teacher union should “take a side” in global political affairs, the OEA also endorsed the “Oakland to Gaza Teach-In” by a two-thirds majority.

Organizing the Teach-In

The Dec. 6 teach-in had three elements: a collection of curricular resources, a virtual panel of Palestine activists, and guest speakers from the Oakland community invited to speak in person in classrooms.We used social media to spread the word and circulate the resources but mostly relied on the OEA for Palestine network that we had built and other connections we had at school sites. We had one-on-one conversations with colleagues about the seriousness of the crisis and the importance of taking collective action as teachers. As one video created by a teacher organizer encouraging others to participate highlighted, the teach-in would allow us to create “more than a statement. . . . You can give kids an aha moment, or maybe even get one yourself . . . [and give] our students a chance to meaningfully interact with the world.”

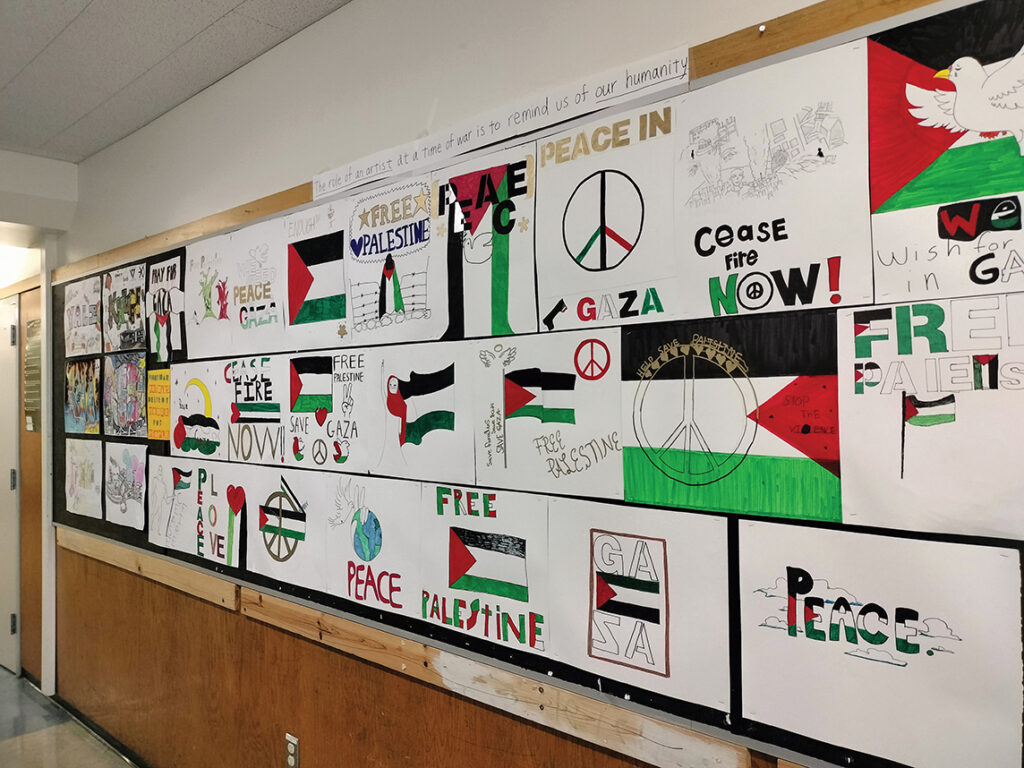

The resources — organized as a non-exhaustive bank of suggested materials rather than a single curriculum — included everything from read-alouds to art projects to math lessons to critical examinations of the conflict’s history. They came from a variety of sources, including the Abolitionist Teaching Network, PBS, Teach Palestine, and UNICEF. In the spirit of liberatory pedagogy, we sought to center voices and stories of Palestinian people. For example, some upper elementary school students read Palestinian artist Malak Mattar’s Sitti’s Bird: A Gaza Story to learn about the reality of war for Gazan children in 2014 and created artwork and writing reflecting on the meaning of “liberation” — libertad — in a Spanish immersion classroom. Meanwhile, one middle school lesson encouraged students to study and discuss the role of art in Palestinian resistance movements. Many teachers also created their own Palestine-related materials, such as one computer science teacher who created a lesson on technology access and restrictions in Palestine and a Spanish teacher who taught a lesson about the Palestinian and Jewish diasporas in Latin America.

The curricular resources we assembled emphasized the complexity of the historical context and the need to present multiple perspectives — including the violent history of antisemitism and its catalyzing role in the Zionist movement. A group of 10th-grade English students, for example, produced voice memos reflecting on their study of excerpts from ABC’s 1988 “Nightline in the Holy Land” broadcast (during the first intifada), which presents side-by-side interviews from “everyday” Israelis and Palestinians on how they see the history of the same land. Another example is Samia Shoman’s “Independence or Catastrophe? Teaching Palestine Through Multiple Perspectives” (see Rethinking Schools Vol. 28, No. 4), which prompts students to analyze both Palestinian and Israeli perspectives on key historical events and culminates in a mock U.N.conference negotiation.

While many teachers, as well as the virtual panelists and community guests, publicly presented their pro-cease-fire stance, the teach-in was focused on providing tools to think through the history of the conflict and analyze the current crisis. The organizers of the teach-in had different opinions on the conflict and the best path toward its resolution, but we shared the conviction that the biased messaging of mainstream curricula (and mainstream media) calls for an urgent correction by educators. Students should know that Palestinians are a people, and their century-long struggle for liberation deserves to be recognized and studied.

The Palestine Curriculum War Raging in Oakland

In the weeks leading up to the teach-in, we found ourselves immersed in the nationwide debate on how — or whether — Palestine should be taught in schools. Many Oakland teachers were already including the assault on Gaza and its history in their lessons. For decades teachers have fought for liberatory pedagogy on the struggles of Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, workers, and other oppressed groups. The inclusion of the Palestinian struggle into the curriculum is a crucial component in this ongoing fight, inseparable from young people’s freedom to make informed choices. In 2020, the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) School Board recognized that certain fields, including Arab American studies, were at risk of elimination from California’s emergent ethnic studies curriculum framework, and therefore voted unanimously to preemptively endorse the uncut curriculum draft (including Arab American studies) and to support the work of the Save California Ethnic Studies Coalition.

On Oct. 31, before the teach-in was planned, OUSD’s chief academic officer called on teachers to “support our students in learning about the human tragedy in Gaza and Israel” and sent out resources and sample lesson plans on the Israel-Palestine conflict and the Oct. 7 attack. Unfortunately, there were major gaps in the district’s resource list. The district included little information about Israel’s bombardment and invasion of Gaza that by then had killed 17,000 Palestinians and displaced 1.8 million. The only reference to this U.S.-backed military campaign was added on Oct. 11 and used loaded media language, such as a timeline noting that 1,200 Israelis “have been killed by Hamas,” but that 1,055 Gazans simply “have died.” More importantly, the official resources did not represent the more than 100-year-long Palestinian resistance against the destruction of their society by occupation and dispossession, which has taken many forms. None of the provided materials were authored by Palestinians, yet the school district included lesson plans by two Zionist lobbying groups, the Anti-Defamation League, and the Institute for Curriculum Services. The former is well known for insisting that anti-Zionism is antisemitism and the latter for lobbying to remove any mention of Palestinians and Palestine from ethnic studies curricula. Finally, the district did not provide any materials for elementary school classes.

These biases and omissions prompted us to assemble the resource bank to supplement the school district’s limited offerings. Educators were encouraged, via union-related chat groups, email lists, and social media, to submit relevant curricular materials that members of OEA for Palestine then reviewed. We also enlisted the support of a few experts from organizations like Teach Palestine. Our supplemental resources — such as a 5th-grade lesson in which students identify violations of Palestinian human rights alongside violations of Mexican migrant workers’ rights in California — reflect the needs of a diverse city like Oakland and continue its tradition of activism and resistance to oppression. As the introduction to the resource bank explained, our goal was “to introduce our students to a range of perspectives and equip them with the tools to engage critically, participate in the discourse, and draw their own conclusions.”

On Dec. 2, following the announcement of the teach-in, Oakland’s superintendent sent an email to all educators and families stating that she was “deeply disappointed” by “the harmful and divisive materials being circulated and promoted as factual.” She also dusted off a rarely cited 2004 board resolution with a lengthy list of expectations for teachers tackling controversial topics in class. The school board president escalated the superintendent’s “disappointment” by effectively threatening to fire anyone who participated in the teach-in, saying to the press “you can’t show up and do whatever you want and not face any consequences.” Their intimidation tactics and media strategy made it clear that our district sided with those seeking to suppress Palestinian perspectives in the curriculum.

We noted two types of criticism of the teach-in: Some critics raised concerns about individual resources. We took this critique seriously and viewed the curriculum bank as a living document. Based on feedback from parents and educators, we edited documents and corrected inaccuracies, vague language, and misquotations, especially anything that ran the risk of being interpreted as antisemitic. But some critics sought to frame Palestinian-centered study as inherently antisemitic and issued statements and threats to prevent the teach-in and to prompt retaliation against participants. Following the Oakland superintendent’s email expressing “disappointment” and the board president’s threat to punish educators, the Deborah Project, a Zionist law firm, sent every principal in the district a cease and desist letter, stating that teachers do not have the legal right to exercise free speech in the classroom. Then media outlets cherry-picked quotations from the teach-in resources to make it seem as if the lessons and materials underplayed antisemitism or the interests of Jewish people. For example, a Dec. 5 Fox News report falsely claimed that the teach-in resources “don’t mention the Holocaust by name,” and cited as evidence one quote, “During World War II, many Jewish people were killed and mistreated,” taken from a worksheet for upper elementary students.

We vehemently oppose antisemitism. Several of the teach-in organizers are Jewish, even Israeli, and are from Holocaust-surviving families. We also oppose the weaponization of antisemitism against the Palestinians, who are denied human and civil rights and are being murdered by the Israeli military. We reject the idea that critique of political Zionism and of Israel as a de jure Jewish state is antisemitic, as well as the idea that winning Palestinian civil rights would negate the rights of Israeli Jews. In the lead-up to the teach-in, we regularly discussed and reflected on the criticism we were receiving — both to differentiate between legitimate critiques and unsubstantiated attacks and to maintain unity and solidarity against the backlash.

How It Went

Despite the school district’s heavy-handed intimidation tactics, nearly 100 teachers across 30+ schools indicated an intent to participate on our registration form, which was circulated a few weeks in advance via school site email listservs, regional site reps’ WhatsApp groups, at school site union meetings, and on our Instagram account. Several hundred students viewed the livestream panel. Across the district, students made connections from Oakland to Gaza, as they participated in seminar-style discussions, analyzed data and graphs, folded paper cranes, produced argumentative writing to defend their claims, created multimedia art projects, made audio recordings of their reflections, asked questions of guest speakers, and so much more — all in English, Spanish, and Arabic. Teachers sent photos and reports of their day to the OEA for Palestine group and shared stories at a debriefing meeting following the teach-in, and we posted them on social media. One teacher said that the resources “opened a really impactful discussion in 4th grade about injustice. The students had a lot of questions and connections.” Another teacher noted that her students did not get to the art component of the lesson because conversation went on for so long. She noted that students were curious about the Jewish diaspora that led to the creation of Israel, the connections between the anti-colonial struggle of Palestinians and that of Indigenous Americans, and why so many people suffer due to the choices of a few political leaders.

Secondary students were similarly engaged during the virtual panel, which included speakers from the Palestinian Youth Movement, Jewish Voice for Peace Bay Area, and the Black Alliance for Peace, and was moderated by an Oakland parent. Panelists spoke about their personal relationship to the Palestinian struggle for freedom, why it is important to them, and how it connects to issues students face in Oakland and the Bay Area. A Palestinian American panelist shared that “for me, being engaged in the Palestinian freedom struggle means rejecting . . . the separation of my land and my people that has been forced on me because of the massacres my grandparents faced.” And a Jewish panelist shared that to him, engaging with the Palestinian freedom struggle means “rejecting Zionism’s attempt to say that the only way Jewish people can be safe is through . . . militarized violence.”

Students then asked the panelists further questions, which showed high levels of engagement and curiosity: “How can we educate our peers about the matter without overwhelming them?” “How can we help or get involved in the Palestinian struggle?” and “Are people in Israel protesting against the war?”

While a few parents expressed disapproval of the teach-in, stating that it would be too “divisive” or “too complex” for children, many Oakland students, parents, and community members reached out via email to express gratitude for the teachers who participated. With their permission, we shared snippets from their messages on our Instagram. One parent wrote:

As an Arab Muslim who was born and raised in Oakland, I experienced the aftermath of 9/11 as a 3rd grader, enduring negative treatment from both teachers and peers, and bullying during my middle school years. Now, as a parent with two children in OUSD schools, I am disheartened to learn that my son has been facing similar challenges. . . . As I review the resources provided, I am overcome with emotion. I am immensely proud of your courage, true leadership, and advocacy for the voiceless. . . . Thank you for your unwavering commitment and for being a beacon of hope in our community.

The day was not without its challenges, but it was an earnest attempt to bring the history, joy, and love to the Palestinian people and their struggle for freedom into our classrooms and students’ minds and hearts.

The teach-in opened possibilities for future organizing, while putting into practice our union’s commitment to international solidarity.

Looking Forward

In the face of attacks and threats, we recognized that our safety as activists is not guaranteed (especially for non-tenured teachers). Nevertheless, it is our responsibility to reject the normalization of oppression. In the context of recent opposition to ethnic studies and liberatory pedagogy, the hostility we faced to the very idea of teaching about Palestinian struggle attests to the necessity of this teach-in. When facing such pressure, we sought to avoid pointless confrontations and remain open to genuine communication with critics, while reflecting on our own practice. Though we have received no reports of teachers and staff receiving official retaliation for participating in the teach-in, the district currently faces allegations of discrimination and antisemitism from Zionist parents and organizations. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights is investigating a complaint against OUSD alleging that the teach-in “discriminated against students on the basis of national origin (shared Jewish ancestry).”

Many teachers were supportive but fearful of being called antisemitic for participating in the teach-in or felt that the issue was “too political” to be appropriate for classrooms. With the current climate of backlash, we understood why our co-workers had these concerns, and it was crucial to engage with them. We facilitated schoolwide meetings and tried to follow up with one-on-one conversations at our schools about what we were doing and why it was important for us to do it.

We learned that we needed to explicitly state our support for the equal right of Palestinians and Jews to live on the land of Palestine/Israel. That is a necessary step to reach some critics of the teach-in who wrongly but sincerely fear that our support for Palestinian liberation is counterposed to concern for Jewish safety or equates to calling for the expulsion of Jews from the land.

The teach-in opened possibilities for future organizing, strengthening relations between educators and other community and social movement organizers, while putting into practice our union’s commitment to international solidarity. We want to connect with and support educators across the country in continuing this effort. We need to help spread and strengthen this work to effectively combat those who are trying to pit Jews against Palestinians to suppress liberatory education. We aim to build on the success of the teach-in and organize further events, bringing more teachers and organizers together in support of Palestine. Organizing this teach-in was transformative. We believe it could be so for other educators who choose to undertake such projects. We hope to hear about more future teach-ins and labor actions that advance the struggle for Palestinian freedom.