What Students Are Capable Of

Sexual Harassment and the Collateral Beauty of Resistance

“We have something to tell you but we’re worried about getting you too involved. We don’t want to get you in trouble,” Baylee and Zaida whispered excitedly as they wiggled through the crack in my classroom door on my prep. I was confused to see them in such high spirits because earlier in the day they had been crushed by news from our administration. For more than two months they had been part of our Restorative Justice club that had been planning two half-day workshops around women empowerment for female-identifying students and toxic masculinity for male-identifying students. The club of 11 demographically diverse students had been urging adults in our building to do something about sexual harassment since October, when they made sexual assault and harassment their Restorative Justice club theme of the month and visited 9th grade classes to lead circles on the topic. This opened up a door for 9th graders to continue to reach out to upperclassmen about the harassment they were facing.

The issues were metastasizing and students hoped to get to the heart of the matter with the two workshops that would explore sexualization, intersectionality, and slut-shaming. They scheduled the workshops for January to give themselves enough time to plan, and for two months — and even over winter break — they worked tirelessly to put them together: sending invitations, making lesson plans, collaborating with strong teacher leaders who gave advice and feedback along the way. This is what made them so devastated to hear from our administration just one week before the scheduled workshops that they had to be postponed because students just could not afford to miss a class or two a couple weeks before finals.

No one seemed more upset than Baylee and Zaida, who had been impacted by Madison High School’s strong curriculum on sex trafficking their sophomore year in health class and carried on the fire for the next year and a half. So when they walked in right before the last bell, I knew they were going to come at me with that same urgency.

“Administration is obviously not listening to us and our needs and sexual harassment has been a big problem since, like, yesterday, so we’re just going to protest,” Baylee said. Mixed emotions of excitement and fear bubbled up in me. It was the moment I wait for every year: seeing students believe in themselves as agents of change and feeling empowered to act on something they care about. It is the aim of our social studies team at Madison to lift up resistance to injustice and provide models for fighting back. Still, I would be lying if I said I wasn’t scared as a kerosene cat in hell when the moment finally came marching through my door at 3:13 p.m. on a Friday.

For the past few months, our school had been dealing with a plague that crept through our hallways and classrooms and was infecting students’ social media accounts. At the beginning of the year, a 4-foot, 11-inch 17-year-old Latinx student had been pushed into a bookshelf when she ignored her male classmate in class. That same week a few 9th graders had come forward about upperclassmen offering $5 to anyone who “slapped that fast freshmen ass” referring to what they saw as the new “crop” of 9th-grade girls. A month later, it came out that a student had cornered a girl in an empty hallway and ran his hand up her thigh. At our talent show, an openly gay African American student and king of dance had homophobic and sexualized remarks posted about him and his dance routine on Snapchat. In the hallways, boys were taking away girls’ cellphones saying they wouldn’t give them back until the girls let the boys follow them on social media or, worse, until the girls would “suck their dick.” It became difficult for females to walk down the stairs without someone staring up their skirts, or up the stairs without someone commenting on their “baddie asses.” Nonconsensual pictures were popping up on secret Instagram accounts of girls, trans boys, and gay boys with pink and lime green free-drawn penises next to their faces. A few 9th-grade girls transferred classes and, in some cases, schools to avoid condoms thrown at them in class — “to be used on them later” — or rulers shimmying up their shirts.

It was not that the administration was not listening to these cases or attempting to address the ones that girls felt safe enough to report. The problem was that all their efforts were obviously not working and they were relying on the one tiny paragraph on sexual harassment in our school district policy for guidance. For many students, it felt like sexual harassment was occurring with impunity. Some perpetrators received only half-day suspensions and when asked what they learned from them, they blithely replied, “I got to sleep in today.” Clearly, more had to be done.

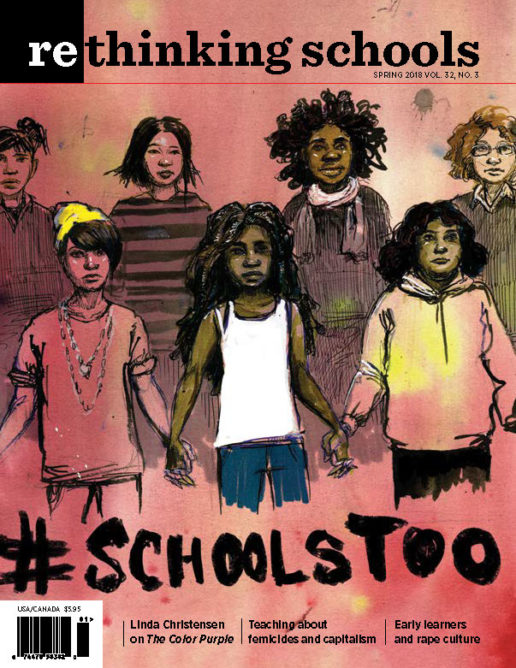

Every time I share these incidents with folks outside the Madison community, they seem shocked. “Wow, your school is so broken,” “Your school is a mess,” “That’s so crazy that it’s gotten that bad at your school.” If this year has taught the world anything, it is that our school is not an anomaly. This year we have seen folks of all gender identities from all across the country and world say “#MeToo,” we have seen the strength and courage it takes to call out behaviors so pervasive and ingrained in our society, and we have seen perpetrators from Harvey Weinstein to Matt Lauer condemned.

But we have also seen what goes unaddressed and unpunished. At the national level we have seen what seems to be countless women come forward with allegations against the supposed leader of the free world with no consequence. And at the local level my students know that communities of color (like theirs) face multiple barriers when dealing with the aftermath of sexual harassment, assault, and violence. Students pick up on this. The only difference between sexual harassment at Madison and sexual harassment at other schools is that students started naming the behaviors that have been ravaging high schools for years, reporting them, and sharing their stories with each other.

I guess the weight of the issue and the strength of the victims who were coming forward beat out fear for my job security that day. So, when Baylee and Zaida asked if they could use our RJ club meeting space and time to reach out to people who might want to be involved, I took a risk and gave them my room. Over the next two weeks, Restorative Justice club hosted three meetings and came up with a plan of action.

Our regular RJ meetings were usually around five to seven students, myself, and our school RJ coordinator/champion Nyanga. I was pleasantly surprised to see 21 students pulling up chairs and forming an amoeba of a circle during the first meeting as RJ club sent out invites to possible allies and leaders they thought capable of changing minds and hearts around the school.

I stepped outside a bit after introductions, still trying to balance wanting to protect myself with the absolute inability to contain my excitement over what was evolving in my room. Outside my door, I ran into Ryan Ghan locking up the computer lab and whispered to him, “I think something big is happening in my room. Students may protest against sexual harassment.” Ryan, a thoughtful and big-hearted teacher who had done a lot to model collaboration and delegation in my first few years of teaching, had just helped with the rejuvenation of our school’s Feminist Club that had fizzled out over intersectionality disputes the year before. He immediately responded, “That’s awesome. It sounds like I should go get Feminist Club?” Bless his heart, because within 10 minutes, 21 turned into 35. Feminist Club and RJ Club combined their powers Captain Planet-style through social media posts, hand-delivered invites, and word of mouth: There were close to 60 participants at the next two planning sessions. By the third and final meeting, the room was packed with the usual suspects but also a large group of trans-men who had just seen a social media post a couple of days before made by a Madison student saying, “I’ll fuck up any faggot who walks into Madison.” There were also four African American football players who were starting to question the toxic masculinity perpetuated by some of their teammates and, at times, themselves. There was a big group from our Latinx student club that had held the weight of machismo on their shoulders and weren’t afraid to spit knowledge about it whenever the room seemed white-dominated. And there was a chunk of our Muslim Student Alliance that was still outraged about a girl’s hijab being ripped off during PE the year before. Everyone had a story and the levels of “me toos” echoing around the room moved the three adults sitting in the corner, watching and listening, and who didn’t do much except bring pizza to fuel the revolution.

As students started to organize and get down to the nitty-gritty of planning over the course of their three meetings, I found myself wanting to ask questions or tell them what they had to do. Bad teaching moves, to be sure. Luckily, the adults in the room held our tongues long enough to discover that every single concern we had would be swiftly addressed within a minute by a student. When I started to worry that students didn’t have a clear purpose, they came up with demands. When I started to worry that they didn’t have a plan of action for what to do based on administration or security’s reactions, they created a multiple scenario script on what leaders should say should they come into conflict. When voices started to dominate, they opened up the conversation. Students showed me over the next two weeks of planning that, when community is at stake, students are capable of anything.

“Whatever We Wear, Wherever We Go, Yes Means Yes, No Means No!”

As the Feminist Club students filed into my classroom during that first meeting, Baylee repeated the purpose: “We basically wanted to protest because we think sexual harassment is a really big problem and we’re not being listened to.” She, Zaida, and De’ja (another RJ club member) went on to explain how their event to educate and take action around sexual harassment was canceled. “This is a problem right now and I think the only way they’re going to see that is if we show them by protesting or walking out,” Zaida concluded. Faisal, a young Muslim student always in for a good cause asked, “Do you think it would be more powerful for us to all walk out together or to all sit in a part of the school and chant or something? Because I feel like if we walk out they might just ignore us.” During that and the other two meetings, I saw students weigh their options carefully and with conviction, ensuring all students in the room were seen and heard.

“I think we should be united and civilized like the Black Panthers,” Baylee said, referencing a strong civil rights curriculum she received from our co-advisor of Feminist Club, Ken Gadbow. “We should all wear black and stand together with a clear message,” Zaida added. “We need demands like in Soweto,” added a sophomore student who remembered our modern world history team’s South African apartheid unit from his freshman year. The students landed on the idea of a sit-in but worried about how to recruit members to join and keep the space inclusive.

“Picture this: We split up into different sections in the school in the morning and march so we can recruit people who are in the hallways going to class,” said a young student who had had experiences with protests in the Portland area. “Maybe we can make up a chant in the hallways so people know what we’re marching for?” said a senior athlete. “Or make a pamphlet or half sheet with our demands,” Baylee interjected. “I think we need to find a way to get more people of color at our meetings,” the co-president of La Raza Unida said as she noticed just three Latinx students in the room. She went to her club meeting the next day and urged all club members to join.

“We need to make protest posters, for sure, and I can do that after school this week. Who can get some poster board?” one of them said at the next meeting. “They always have leftover cardboard in the library,” suggested a library TA who always helped with our culturally relevant library displays and is transgender. Worried about low participation due to semester finals around the corner and inspired by the action at the Golden Globes that many students had reflected on in our gender studies classes, students also started posting pictures of the Time’s Up logo on their Instagram accounts with a caption explaining to wear black on the day of action against sexual harassment and assault (Jan. 17) and to “DM me for more information on how to get involved.”

We ask students to be supportive group members in class so often. We ask them to check in on their group mates, to help them get unstuck, to listen to others’ ideas, to not miss class and leave their group hanging. Sometimes it works beautifully, and other times it’s disastrous (is that just in my classroom?) and I think we’re never quite sure how that lesson lands with our students. What I saw over the course of just a few meetings was students getting to each meeting on time, planning carefully, collaborating wholeheartedly, and making the best of the resources at hand. By the end of their last meeting, their demands were written and the plan was set:

1. Actual consequences put on perpetrators of sexual harassment.

2. A clear, written policy on sexual harassment now from administrators and a plan to prevent it by Feb. 7.

3. A written statement from Portland Public Schools by Feb. 17 stating how they will protect students and create a more supportive environment for victims. We demand to know what actions they will take and how they will take accountability for their neglect of these situations.

Students would march from the cafeteria where there would be a crowd getting breakfast and through the social studies hallway where they felt they had the most teacher allies. They would chant “Whatever we wear, wherever we go, yes means yes, no means no!”

The Talking Stick: Lip Gloss

Jan. 17, excitement was unbelievably high for so early in the morning, as students filled up the C-crossroads — a fancy name for a wide hallway in the middle of our school’s second floor — and their chants echoed through the school. The hallways were alive as teachers and students peered out doorways and, in some cases, ran to the center of the school to join. At 8:21, about 100 students started to find their seats on the ground.

Organizers had done a lot to prepare for this moment. They had written up a press statement and created a multiple scenario script of preplanned responses to administration, security, or students opposed to the sit-in. As the 100-plus students started to settle onto the ground, they started to look around for a leader.

“Alright everyone, we’re going to be here for a while I hope, so let’s talk,” a student organizer said. As administrators and security popped in, seemingly unsure of how to respond and taking pictures occasionally, the most organic and exquisite restorative justice circle commenced. For seven hours, there would be a constant presence of well over 100 students seated in a circle in our main hallway sharing their stories and concerns. Some students joined for just one class period or for a 15-minute “bathroom break” and others stayed the whole day. A good number of teachers came to listen, learn, and witness our courageous students following the restorative justice practices our school had prioritized since our current seniors’ freshman year. The talking stick: lip gloss. The centerpiece: student protest posters. The theme: students’ demands and stories. The rest grew from there. Students raised their hands if they wanted the lip gloss in order to speak and listened with a full heart to some harrowing tales of harassment and inspiring ideas for prevention. When disagreements came up, they were addressed with an incredible level of respect and maturity. When a young African American 9th grader said she didn’t want her younger sister “dressing like a slut” when expressing the importance of being a good role model and teaching siblings better than to harass or assault, hands went up.

“I think I know what you’re trying to say,” one theater student started, “but I think a lot of people are uncomfortable with the word ‘slut’ because they don’t want to be ashamed and it takes their own agency away. You and I should be able to dress however we choose and we should be shaming those who harass us or make us feel bad for that choice, you know what I’m saying?”

The freshman heard a few more stories and opinions on her word choice and, when I feared students were over-policing word choice and pushing out a student of color from their movement, she bravely stood up and asked for the lip gloss, apologized for the way her word choice landed, and restated her point without using the word again.

When a couple of students started naming perpetrators, Mitch, who had been tirelessly reaching out to media all week, urged us to follow the Madison-wide restorative justice norm of confidentiality during class circles. “It’s important to name harassers in reports to the principals and stuff but we should focus on our stories here and not name names.”

When the conversation turned female-dominated, a male Step Up advocate requested the lip gloss. “I think one thing we can do as men of color and anyone else, really, is to do what we’re doing now. Have these conversations with our friends, our family. I have these talks with my friends all the time and it’s important to reflect and make sure we’re being thoughtful in our interactions with girls.” This call for self-reflection obviously landed well, as a little while later, a young Latinx male talked about a time when he wished he would have made a better choice and expressed gratitude for his brother, who modeled positive relationships with women.

Sometimes there were disagreements. Sometimes students paused to teach each other what sexual harassment looks like (“Unwanted stares can be harassment, too! Some boys around here exoticize us hardcore,” a young Vietnamese student said.) And sometimes there were chilling stories, like when a sophomore girl was invited by an upperclassman to go to a convenience store over the weekend and was told she was going to be kicked out of the car unless she performed oral sex.

For seven hours, though, there was never a lull.

Celebration and Reflection

As the last bell rang and more than 120 students stood up and stretched their tired knees, organizers looked across the breaking circle at each other with pride. They had done it. Baylee sent me a text from across the hall asking if we could debrief in my class. We all plopped down on my couch and sighed. They has triumphed over trauma and made something beautiful out of something hard with the unwavering magic of their voices.

Students went over their exciting meeting with administrators and Nyanga congratulated them on their bravery and strength. I expected students to bask in the glory of their success: Administrators were currently writing a statement and hashing out a policy that would be returned to students by the deadline imposed in their demands, and the head of our district high schools had heard their concerns. Students had won — our school had won.

Instead, they used this time to bring up things they wished they had done and hoped to do better next time. “Remember when Ivan had his hand up for, like, 20 minutes and a bunch of white girls got to speak before him?” Ivan is a Mexican American sophomore who, indeed, shook his head every time a “hipster” girl was called on before him. “Yeah, we need to be better at calling on people of color since they seemed less likely to speak in the circle,” Baylee said. “Not because they didn’t want to but maybe just because they needed more wait time or something,” De’ja added.

I was proud of my students for seeing the room for growth in their accomplishments while still heading to the bus at 4 p.m. with their heads held high, ready to see the change their sit-in brought to our community.

Camila Arze Torres Goitia (carzetorresgoi@pps.net) teaches at Madison High School in Portland, Oregon. She wrote the article “Colonizing Wild Tongues” in the Summer 2015 issue of Rethinking Schools.