What’s Your Story?

Student identity on the walls in Philly

Illustrator: Current and former students at Kensington High School for the Creative and Performing Arts

Our public art project, 24 8×10-ft. banners with student photographs and writing, had just been installed on walls in the community around our school. We received an email from the owner of the building where Natasha’s work had been installed. He asked us to respond to one of his tenants, who had questioned the “dark content.” We wrote the tenant, explaining that our intent was to amplify the voices of our students and show that their stories matter in our neighborhood. She responded:

Very cool project, and I’ll always support anyone trying to express themselves. . . . The people walking along the street here need to be and feel uplifted, not reminded of pain (in my opinion).

People expect student work, especially from our most marginalized communities, that either projects overt positivity or evokes pity. But this does not accurately reflect the complex lives our students live. It is not the burden of our students to uplift others; the beauty and depth of their stories stand on their own.

What’s Your Story? was an interdisciplinary effort. Josh was a media arts teacher and Charlie an English teacher at Kensington High School for the Creative and Performing Arts (KCAPA). KCAPA is a neighborhood public school in Philadelphia. The majority of its 500 students are Latina/o; about 30 percent are African American and 10 percent white. All of KCAPA’s students receive free or reduced-price lunch.

KCAPA is located at the southern end of Kensington; most students travel from the northern, more predominantly Black and Latina/o parts of Kensington. The area around the school features some of the most heavily gentrified space in Philadelphia. In many ways, our students feel like visitors in the school neighborhood. By hanging their faces and work on buildings in the community, we intended to show that they belong in and contribute to the community.

The context for What’s Your Story? was the ongoing, systemic neglect of Philadelphia schools. The previous year, 2013, our students tried to get an education in a school system that was in its worst condition since a state takeover in 2001. Two dozen schools closed their doors that June, forcing more than 7,000 students to find another school. We lost more than 4,000 teachers and support staff. KCAPA was no exception, devastated by cuts as students from closed schools flooded in. Even with “arts” in the name of the school, austerity left the school with a paltry offering of arts courses. In this context, we found it especially important to incorporate opportunities for artistic expression into traditional academic classes.

As we conceived this project in fall 2014, the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, the Ferguson uprising, and the rise of #BlackLivesMatter were also on our minds. We wanted to give students an opportunity to explore the complexities of their identities, and to present publicly to a society that so often attacks or makes their identities and bodies as young people of color invisible.

So we decided to combine multiple styles of photography with different types of writing to encourage our students to explore their identities from a variety of perspectives. We knew that these stories would not be all bright nor all dark. As Natasha closed her poem, “Everyone has they falls.”

Finding Inspiration

Over the previous two years, Josh had worked with students on several public art projects. For example, he had asked students to respond to the state of the schools with an installation based on Wendy Ewald’s American Alphabets with 26 outdoor graphic panels that students titled Alphabet of Hope and Struggle (e.g., C is for Crowded, P for Prison, and R for Resistance—see Resources for link to complete alphabet with images). In early conversations about the alphabet project, some students expressed apathy or cynicism. James said: “Our little school project isn’t going to change their minds. It’s not like we’ll just get our teachers back the next day.”

But slowly, through the development of the project, the most critical students became those most invested in the work. The following year, Josh’s media classes published Stitched, which used archival material to draw connections between the school’s past and present realities.

These experiences were the impetus to publish student work in increasingly public ways. And, along the way, many of Josh’s students developed the photographic and technical skills necessary to execute and help lead a project of this scale.

Charlie joined the staff of KCAPA in the middle of the 2013-14 school year. When he saw the alphabet project, he approached Josh about collaborating the following year on a public project about identity.

English Class: Exploring Identity from Three Angles

We agreed to start by guiding students to dig deep into identity: their family histories, perceptions of themselves, and how they want the outside world to see them. After introductory activities defining different aspects of identity, Charlie began the English portion of the project: three pieces of student writing that would work together to create complex visions of student identities. Charlie decided to focus on three questions, each linked to a different genre (both the “raised by” poem and the “Danger of a Single Story” essay were inspired by projects described in the pages of Rethinking Schools by Linda Christensen—see Resources):

- How do others perceive my identity?—”Danger of a Single Story” essay

- What has shaped my identity?—”raised by” poem

- How do I see my own identity?—six-word memoir

For each of these assignments, the focus was on producing high quality work, rather than the massive quantity of work normally expected by schools. Most days, Charlie found time for students to read work aloud.

They began with a conversation about the “single stories” that are placed on students’ identities. The English classes watched and discussed Chimamanda Adichie’s “Danger of a Single Story” TED Talk, and read mentor texts by Black journalist Brent Staples and Linda Christensen’s high school students, focusing on how each developed their ideas using vignettes. Over the course of two weeks, Charlie had students brainstorm single stories told about them, identify and describe moments in their lives that illuminated the impact of those single stories, and weave together a narrative essay. He taught them how to use peer revision to refine their work.

Students explored assumptions others attached to them based on race, gender, age, and religion. For example, Bianca focused her essay on perceptions of herself as a mother. She described an incident that took place in a corner store when a woman noticed that she was pregnant and asked how old she was:

I told her I was 17, and she was like, “Oh, wow. That’s too young to be a mother.”

I told her loud and clear: “Just because I’m young and pregnant does not mean I am going to stop going to school. This baby is actually my motivation to never quit and try harder.”

Then the students dove into a study of poetry. They studied Kelly Norman Ellis’ “Raised by Women” as a mentor text. Charlie also had students explore a variety of other poems as possible mentor texts. en students wrote their own “raised by” poems.

Some students, like Vidura, stayed close to Ellis’ mentor poem, incorporating description and dialogue to make his house come alive:

I was raised by some religious,

Barbecuing, football watching

“Come on ref, that was out of bounds!”

type of men

Helena wrote:

I was raised hearing,

“You know I’ll always love you”

But did she love the drugs more?

Well she’s clean now.

Kind of Mom.

Other students decided to take the “raised by” prompt and move in a different direction in form or structure. Some, like Jeffrey, pushed back against the original prompt, ending his poem:

So no, I wasn’t raised.

I survived.

As the essays and poems were in the process of revision and submission, Charlie asked students to excerpt their own work, pulling out a particularly evocative line or stanza for the public art portion of the project. This was a challenging process for many students, and Charlie spent a lot of time prompting students to consider the most central idea of their poetry or writing, and what piece of their work would best represent that larger meaning.

Through the excerpt process, Julian came to an entirely new opening for his essay. For his first two drafts, Julian opened his essay: “If somebody calls you a follower prove them wrong. Make them say that you are a leader.”

Then, as Julian was working on his final draft and the excerpt that would appear with an image, Charlie checked in. He asked Julian, “What do you think about your opening?”

“I think it’s OK, but it could be better.”

“What are you really trying to say when you talk about being seen as a follower?”

“Even when I was in elementary school, everybody thought I was going to end up like my brothers.”

“Can you think of another way to sum up that idea?”

At that point, Charlie walked away and left Julian to brainstorm and write. In the end, he decided on a different opening, which also became his excerpt: “All my life, I felt like I was trapped in my father’s and brothers’ shadows.” His original opening found its way into an expanded conclusion. His excerpt fit perfectly with the artistic vision of the photographic portion of our project.

Working on the excerpts took conversations about refining their work to the next level—encouraging students to look closely at precise word choice. That created a strong segue to the six-word memoirs.

Charlie introduced this project to his students by asking, “If you only had six words to tell your life story, what would you say?” They watched a video compilation of six-word memoirs and read more examples from various sources. Charlie asked them to identify which memoirs stood out and why.

Then he showed them 10 versions of his own memoir. “So originally,” he explained, “I wrote, ‘White man investing in Black history.’ I liked the overall idea, but I didn’t think it sent exactly the right message. So I decided to find synonyms for the most important words. I thought about words I could use to replace ‘man’ and came up with male, dude, guy, gentleman, and bro.”

At “bro,” there were laughs from the class.

“So why is that funny?” Charlie asked.

“Because that’s something we would say,” replied Nazir. “But it’s not the way we’d expect you to say it.”

“Exactly. In the end, I decided on ‘guy.’ It felt like it fit me as a person and as a teacher. It had just the right mix of formality and informality, and was positive, but not overly so.”

Then he asked the students to write 10 six-word memoirs. After some initial pushback (“Why do we have to do 10 versions? This is extra!”), students found that later drafts of their memoirs more accurately reflected how they saw themselves. Our student Josh’s first memoir read: “Philly never knew me at all.” After playing around with synonyms, he settled on: “Philly never experienced me at all.” In the reflection at the end of the assignment, he wrote: “The word [choice] can make it pop more. It makes it more powerful and meaningful.”

The students’ memoirs ranged from hilarious: “Video Games? Or Homework? Video Games!” To perceptive: “What did you say? Speak up.” To darkly beautiful: “Time heals wounds and leaves scars.” To uplifting: “Five feet and still the biggest.”

Their work emphasized for us the importance of taking the project beyond the walls of our school—to people who don’t often see or acknowledge the complexity of our students.

Photography Class: Visualizing Student Writing

Meanwhile, we began to work on visual images. Although some students were in both of our classes, students in Josh’s photography class formed the core team responsible for the visual art. We drew heavily on previous units in the class, as well as from Wendy Ewald’s In Peace and Harmony: Carver Portraits (see Resources). Josh knew and admired this project, and could envision similar work in our neighborhood. He hoped that students would emulate and expand on Ewald’s level of artistry, creating images that rose to a professional aesthetic. As Charlie guided his English students through crafting their single story essays, Josh’s class had to decide on the imagery to pair with the essays. Our goal was to photographically represent something complex: How do you use photography to explore inaccuracy, when photography is inherently such an accurate medium?

Earlier in the year, the photo class had worked on a small-scale public project based on silhouettes the students took of each other. Josh thought that silhouettes would pair well with excerpts from the single story essays, but he wanted the students to make the connection for themselves. So he had the class screen a video series produced by George Eastman House on the history of photographic processes. After the class watched content about the history of the silhouette and its place in reproducing the human image, Josh asked: “What do you think? Can a silhouette represent a person accurately?”

“A silhouette is an exact copy of the outline of a person, right?” Ana confirmed.

“Yeah,” Lewis said. “But it has no information inside of the outline, it’s just black. If you know the person, you know who it is. But to an outsider, a silhouette isn’t really helpful; they have to make up their own image of your face.”

The students made the connection that we hoped they would: The partial information given to us by a silhouette would pair well with the incomplete single stories that our students were writing about. Within the blank space of each student’s profile, they could add their own words in white, filling the empty outline with their individual stories.

Together, the class experimented to find the best photographic techniques for what we needed—a black silhouette with a clean white background. They set up a small studio using two flash units pointing directly at a white paper backdrop. Standing in front of the light, lit only from behind, students took practice photos. After some basic photo editing, the resulting images gave us the silhouette we wanted. The photography students pulled small groups of students from Charlie’s three English classes until all silhouettes were shot. Files were handed off to a team from the photography class that used Adobe Illustrator to turn the photographs into black-and-white line art. The resulting silhouettes were ready for writing and could be scaled to any size.

Next, it was time to tackle art for the six-word memoirs. Many students spend their days interacting with social media through photographs of themselves and others. This selfie culture offers a natural connection to more intentional experimentation with portraiture. The class previously had discussed the legitimacy and power of self-expression of this approach, and suggested that portraiture would work for the six-word memoirs. “If we wrote six words that we think accurately represent ourselves,” offered Thalia, “shouldn’t the photo be of us how we want to look?”

Josh had the good fortune of a small and devoted class, and many decisions were truly collaborative and born out of dialogue. Together, they decided that teams of photographers would go out with small groups of students to shoot against natural backdrops in the blocks near the school. The teams used a single battery-powered ash to control the light hitting their model’s face. A photographer helped the subject feel relaxed while one assistant held a large diffusion panel in front of the flash to soften the shadows, and another used a reflector panel to balance the light back onto the opposite side of their face. The most common phrase we heard the photographers recite before their first photo was “Just be yourself.”

Finally, to start a conversation about what imagery to pair with the “raised by” poems, Josh asked his class to bring in a favorite family photograph. He had watched students become heavily invested in archival photography during the Stitched project earlier in the year, and thought they would latch onto this in a similar way. Many students brought full envelopes of prints, and the class excitedly shared images and recalled the events recorded in them. We asked everyone in Charlie’s English classes to collect their favorite photos, and all the photos were carefully digitized by a team of student archivists. Even small images were scanned at a high resolution for large-scale reproduction, and we were able to hand students’ photos back to them along with a digital version to share with family and friends.

In Nissa’s “raised by” poem, she explored her own and her family’s relationship to gender:

Really though, I was raised by my dad who would tell me I was meant to be a boy when I was in the womb.

We’d be in the room shadow boxing. He’d hold his palms up and I would punch.

Left . . . right . . . uppercut . . .

Nissa paired the excerpt of her poem with a candid family photo: her sister dressed in pink, holding a new Barbie doll; Nissa, in grey, staring into the lens.

It was finally time to put the words and images together. We gave students 8.5 x 11-inch digital copies of their family photos, portraits, and silhouettes, and sets of matching transparency sheets. Students laid the transparencies over the images and wrote on them with black permanent markers, trying various versions of their handwriting. We insisted that they use their own handwriting. It personalized their words in a way that couldn’t be expressed using a digital typeface.

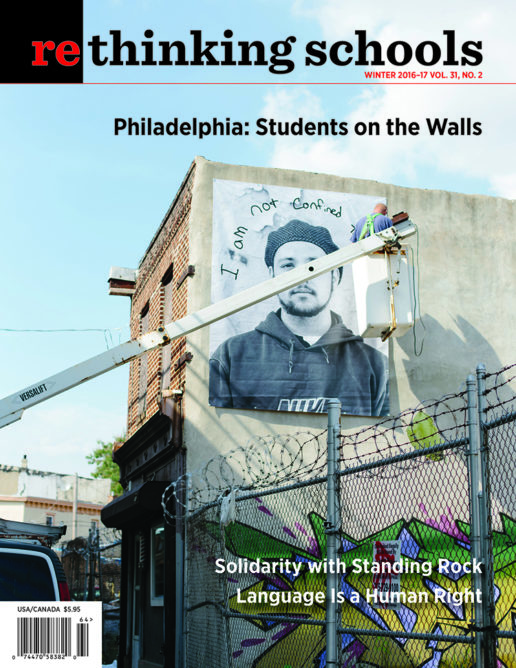

Taking the Message to the Walls

With support from The Galleries at Moore College of Art and Design and our own fundraising, we were able to have eight triptych (three-part) sets of banners professionally printed and installed. We walked, biked, and drove around on the lookout for large blank walls that could accommodate our banners. After attending community meetings, knocking on doors, making calls, writing emails, and reaching out to anyone who might help, we secured a group of sites, including our school, a barbershop, a woodworking studio, private residences, artist studios, and a Verizon telephone exchange building.

With 72 complete sets of work, we had students vote on which sets should be on public display in the neighborhood. We hung the sets, numbered 1 through 72, on the walls, and had students walk around the room, taking time to look at all the sets. The students chose their top three. When the results came in, we were overwhelmed—55 of the 72 sets received at least one vote. Banner printing was scheduled to begin the following week, so we knew that we, as educators, would have to use student input to hash out the final decision. We laid out all 55 with a focus on the top 20 vote-getters. We realized that we would need to mix and match the sets to include as many students as possible in the most public portion of the display. Ultimately, we decided to hang six sets with thematic combinations of work from three different students each, and two sets with all three pieces from the same student.

We had more high-quality student work than the 24 pieces we could hang on walls, so we needed additional ways to share the project to compound its impact—for our students and for the broader public. We shared the work as many ways as we could. We created a website to house all 72 triptychs, and linked student writing and audio of classroom readings. We used #kcapawhatsyourstory to share the work on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, and posted maps to help people find the physical sites. We published a printed catalog that included full-color reproductions of all student work. Our students led tours for 9th graders, the press, and the public. We presented at multiple conferences and put up a gallery exhibition at a nearby cafe. Everywhere, we incorporated student voice and encouraged students to participate and present.

More Than I Thought It Was

Throughout the project, we collected feedback from students, including reflections after each portion, an overall reflection, and check-ins after events. After the project was installed, we held a fishbowl-style Socratic seminar in the English classes to help students synthesize our months-long work on identity, literature, and public art. On the first day, half of the students sat in the inner circle and participated in the conversation, while the other half sat in the outer circle and observed a specific student. The next day, the circles switched. Students said that the most powerful part of each aspect of this project was hearing from their peers and being heard themselves:

“It made me feel a little more understood.”

“It was very encouraging because I knew they were listening and I had my voice heard.”

“I liked that people came up to us KCAPA students and called us intelligent.”

“I learned that everyone has a story to tell.”

“My identity is more important than I thought it ever could be. I learned that my life is more than what I thought it was.”

A banner featuring Kyron’s poetry and a childhood picture with his twin brother still hung on the back wall of Rossi Brothers Cabinet Makers, across the street from the school. Kyron said, “Every day I go to school and I see my work across the street. I’m really happy about it.” He told the local newspaper, the Star: “I think everybody who sees these will get a taste of all of our different identities. They’ll get to know people better, even though they don’t know them. They can have a relationship just by looking at it.”

It shouldn’t be exceptional for students to feel heard and understood in our schools and communities—but for our students it was. Philly students continue to attend schools that are unstable, under-resourced, and overcrowded. Nationally we have seen the killings of Sandra Bland, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and many more at the hands of police. With the election of Donald Trump, our students, especially those from Muslim and immigrant backgrounds, are experiencing increasing levels of fear and anxiety. Trump triumphed using overt appeals to white supremacy that treats our students as “other.”

Whether in a circle inside the classroom or on the wall of a barbershop up the street, being heard is critical to our students. We need a thousand creative ways for them and their powerful work to reverberate beyond our school walls.

Resources

Alphabet of Hope and Struggle. kcapaphoto.org/alphabet.

Christensen, Linda. Spring 2007. “Raised by Women.” Rethinking Schools (21)3.

Christensen, Linda. Summer 2012. “The Danger of a Single Story: Writing essays about our lives.” Rethinking Schools (26)4.

Ewald, Wendy. 2005. American Alphabets. Scalo. Print.

Ewald, Wendy. 2005. In Peace and Harmony: Carver Portraits. Hand Workshop Art Center. Print.

Inside Out Project. insideoutproject.net.

KCAPA What’s Your Story?

kcapaphoto.org/whatsyourstory.

SMITH Magazine. Six Word Memoirs.