What Nina Simone Teaches 1st and 2nd Graders About Making Change

On the carpet, children listened intently for more than a minute as Nina Simone played the piano before beginning to sing in a video of her 1976 performance of “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” When she heard Simone sing “I wish I could be like a bird in the sky. How sweet it would be if I found I could fly,” Kaylee inhaled audibly. She leaned over and whispered to Sienna: “’Cause the bird’s free and that’s what she wants for everyone.”

At the end of the song, Gia smiled and said “Al final de la canción dice que se siente free. [At the end of the song, she says she feels free.]”

Matsumi gesticulated with strong hands and a loud voice, imitating Simone’s powerful finale. “Ella es muy fuerte al final y usa su voz para estar free. [She’s very strong at the end and uses her voice to be free.]”

After playing this song as part of our changemakers unit, the children were clamoring for “more Nina.” Though Kaylee seemed to understand Simone sang for freedom for everyone, she didn’t share this idea with the whole class. Our teaching team wondered: How could we help students understand that Nina Simone’s message was about a collective experience of freedom? How could we teach them how many people work together to make change?

I work with around 40 multi-age (1st- and 2nd-grade equivalent) students in a Spanish dual-language program at UCLA Lab School, part of UCLA’s School of Education & Information Studies. My three-teacher team works across two connected classrooms that allow children and teachers to work collaboratively. Our student population reflects the racial and ethnic diversity and neurodiversity of children in California; students come from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. Many conversations in this article have been translated from a rich array of Spanish and English. We encourage students to use their full linguistic repertoires and honor the many ways children “language.”

At the beginning of each academic year, our teaching team and the teachers who teach our level decide on an idea to connect all subjects. Guided by our inquiry approach and some of the Common Core and Learning for Justice social justice standards, our universal idea was Poder y Cambio [Power and Change]. As we taught environmental science, composed and listened to poetry, wrote biographies and argumentative writing, and danced, we returned again and again to Power and Change. We introduced students to a variety of changemakers through read-alouds paired with videos or other primary sources related to each changemaker (see Resources). During the unit, students also wrote a biography and created a papier-mâché bust of their chosen changemaker. We asked: What does change mean? What does it mean to have power? What does it mean to be a changemaker?

Yet we wanted to go beyond a traditional approach to changemakers. So often changemaker units have students research individuals working to change a variety of issues in their respective places/times. We wanted students to understand how individual actions can contribute to a movement. By the end of the unit, we hoped children would have an understanding of ways to take action in the face of injustice and come to see themselves as changemakers — not just as individuals, but as part of a community movement.

We read No Voice Too Small, a nonfiction book about young changemakers using their voices, and ¡La lucha de Alejandria! (Alejandria Fights Back!), a fictional book about 9-year-old Alejandria organizing and taking action in the face of unjust landlords and gentrification in her neighborhood. We read about Muhammad Ali, José Andrés, Claudette Colvin, Mari Copeny, Jasilyn Charger, Sharice Davids, Dolores Huerta and César Chávez, Sylvia Mendez, and countless other changemakers. Students were fascinated by Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm; painter Alma Thomas; cartoonist Jackie Ormes; and queer Black singer, songwriter, and civil rights activist Nina Simone. We wondered how we could help students make deeper connections to these women and the activism of the civil rights and women’s liberation movement, as well as power and change in the present.

We especially wanted to follow students’ interest in how Nina Simone used her voice to take action in the face of injustice. We knew that along with Simone’s music and interview about what it means to be free, we could use Traci Todd’s beautiful picture book (see Resources). Throughout our conversations, students begged to rewatch and listen to more of Nina Simone’s performances. We hoped another song might plant a new seed in our learning journey.

Music as an Empathy-Building Primary Source

After Kaylee’s comment about Nina Simone singing for everyone to be free, we decided to highlight Simone’s “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life.” Manolo listened on the carpet, lips parted and brows furrowed, and started repeating lyrics: “Ain’t got no home. Ain’t got no shoes. Ain’t got no money. Ain’t got no sweaters. Ain’t got no love!” He turned to Cecil, ruminating and repeating: “Ain’t got no water. Ain’t got no air!”

“Wait, wait, wait!” Cecil exclaimed. “We gotta hear these words again. Can we play it again?” I nodded so as not to speak over the lyrics that so engaged the kids.

After the song ended, Gia quietly raised her hand. “There was a list of things that she doesn’t have and then I heard her say, ‘What have I got? Why am I alive anyway?’ That was important!”

“Then there was a list of stuff she had like her hair and her body and her brains and I think she has a voice to sing this song,” added Gio.

“Why don’t we listen carefully one more time, like Cecil suggested?” I said. “Let’s think about her two lists and what they mean.”

We played the song again. Students listened closely.

“¡Escuché [I heard] I’ve got my smile!” Román shouted at the end. “I’ve got my heart. I’ve got myself.’” I drew a line on the whiteboard, ready to sort and document what children noticed for each list. The children had different ideas though. Henry stood up, excited to share.

“¡Ella está hablando de muchas personas! [She’s talking about lots of people.]” Henry said. “¡No está hablando solamente de ella! [She’s not just talking about herself!]”

“Está hablando por las mujeres y las personas de color [She’s speaking for women and people of color],” Cecil quickly agreed.

“¡Y por las personas que necesitan algo — que tienen injusticia! [And for people that need something — that have injustice!]” Wesley added.

“Can we learn more about that?” Kaylee quietly asked. “The people she’s singing for? Like who are they? Do you know?”

I was thrilled about this unexpected conversation. I told the kids we could think about Nina Simone’s time and the people she might be using her voice for soon. If we could contextualize Simone’s time and place, perhaps students would start to understand who Simone was singing for and why.

Perspective-Taking Through Primary Sources

At lunch, my teaching team talked about Kaylee’s beautiful question “Who are some of the possible people and changemakers that Simone sang for?” Certainly, we couldn’t give an exact answer. Only Ms. Simone could do that. But how might we respond? Who are, were, and will be the people for whom Nina Simone sings?

Nina Simone’s career and activism spanned the Civil Rights Movement into the women’s liberation movement. Looking for another primary source for students to analyze, we decided to use Jan van Raay’s photographs of artist strike protests. We shared two of van Raay’s photographs from 1970: 1. Faith Ringgold, Michele Wallace, and other artists at an Art Workers’ Coalition protest in front of the Whitney Museum; and 2. A Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, Art Workers’ Coalition, and Guerrilla Art Action Group protest in front of the Museum of Modern Art. They portrayed mostly Black and Brown women but included men and at least one white-presenting person. Some people carried signs in front of museums that read, “50% BLACK WOMEN ARTISTS” and “BLACK and PUERTO RICAN ART MUST BE REPRESENTED.”

We introduced the photographs. “Historians think about specific times and places,” I shared. “Nina Simone’s ‘Ain’t Got No, I Got Life’ gives us clues about the late 1960s and artists and activists working around that time. Since Nina often performed and lived for a time in New York, we can only guess at Kaylee’s question ‘Who was Nina singing for and with?’ Jan van Raay’s photographs of artist protests also came from this time and place and might give us more ideas about Power and Change. In these protests, people were demanding equal representation for Puerto Rican, Black, and female artists in fancy museums that mostly exhibited art by non-Puerto Rican, non-Black, and non-female artists. We know from studying Alma Thomas that not everyone’s art is always valued equally and not everyone has the same opportunities to show their art in the largest museums.”

The children looked at each of Jan van Raay’s photographs in small groups, talked about what they noticed and wondered, and documented their thinking on Post-its and directly onto the copies of the photographs we made. Then we had a whole group conversation. The children made interesting connections between the two protests.

“In this picture [second protest picture], they look mad,” Chet said, “but here [first picture] they’re all smiling.”

“I think they’re happy to be together but it’s a sad reason,” Pichi added. “There’s different types of people even though it seems like it’s all for mujeres y personas de color [women and people of color]. Miren a estas personas [Look at these people].” Pichi pointed to white- and male-presenting people.

I was surprised most by the children’s discussion of van Raay’s first picture, which included a deep interest in a person with their back turned to the camera, who appeared to be walking away from the protest.

“Creo que ese hombre ahí está caminando y pensando GRRRR [I believe that man there is walking and thinking GRRRR],” Gia said. “Esas personas no deben marchar. No necesitan nada. ‘GRRRR.’ [These people shouldn’t march. They don’t need anything. ‘GRRRR.’]”

“Yo pensé que esa persona está pensando ¡Qué bien! Muy bien para ellos. ¡Hurra! Go for it! [I thought that person is thinking ‘That’s great! Very good for them. Hurrah!]” Cecil added.

“Mmmhmmm,” Manolo said. “Está pensando no soy afroamericano pero me gusta. [He is thinking I am not African American but I like this.]” Manolo gave a thumbs up.

Children had created opposing narratives about a person whose face they couldn’t see. In Gia’s imagination, the faceless person was a racist. In Cecil and Manolo’s minds, the person was a white ally. The perspectives that surfaced gave us information about the fact that children knew that people could make choices about participation in protests and anti-racist or racist ideas.

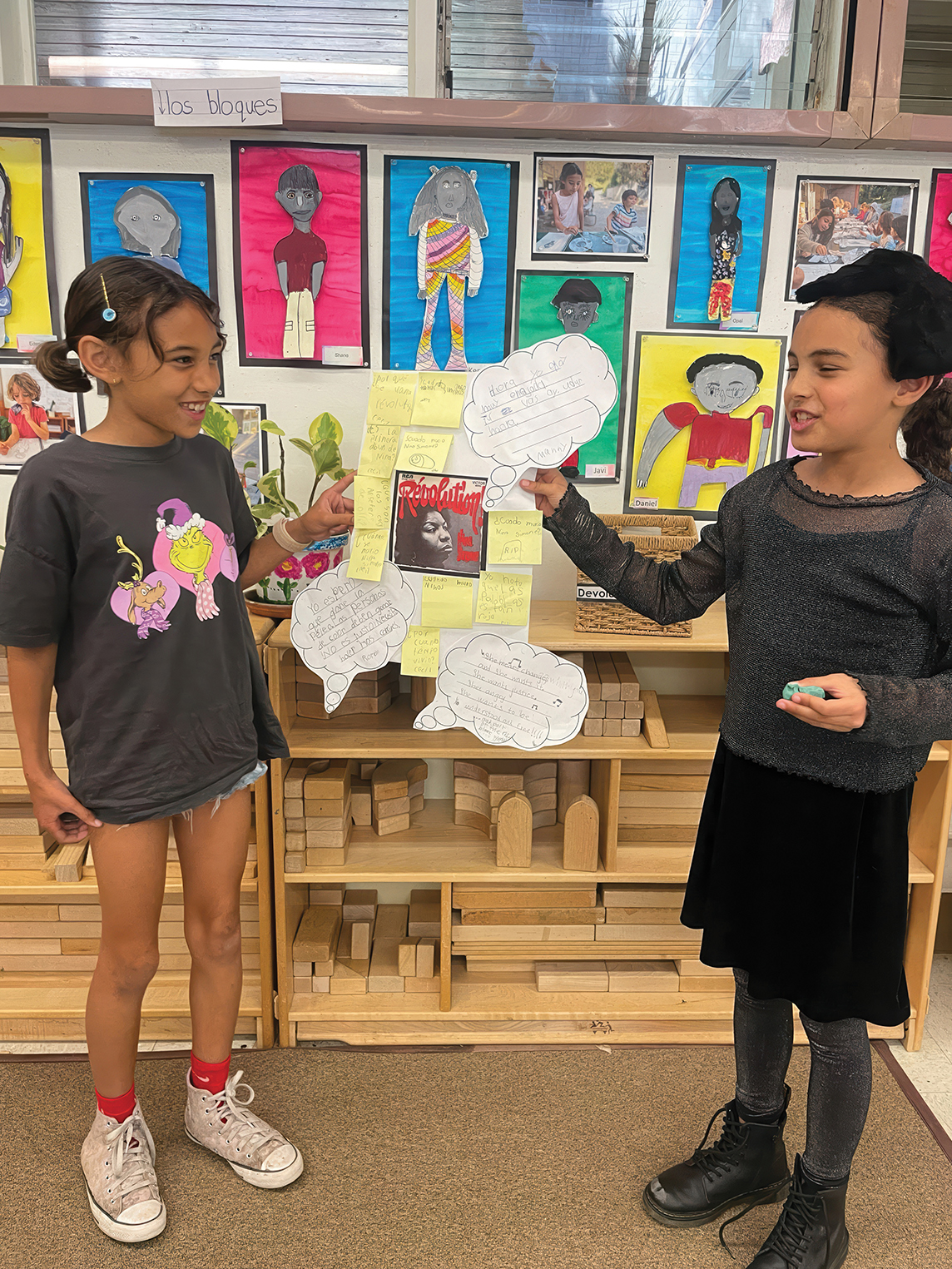

After the discussion, children filled in thought bubbles that our teaching team had photocopied. The students could write or draw and place their thought bubble next to their chosen person.

Interestingly, students continued perspective-taking by filling in thought bubbles for people whose faces and expressions were visible and the faceless person with their back turned to the camera. Afterward, children did a gallery walk to view everyone’s thought bubbles and share final ideas about the protests.

“Todos merecen una voz y oportunidades [Everyone deserves a voice and opportunities],” Serene shared. Many children nodded, showing agreement with hand signals.

“People of color were disrespected and people stood up for themselves and others,” Gia added. “Plus some other people made a good choice to help too. They continue doing it until they are free.”

“You can always change something,” Matsumi said. “Everyone should always have the right to be who you are and show yourself to the world. And you stand up for rights for other people if they haven’t been treated well.”

Children were developing their own ideas about power, change, representation, and intersectional allyship against entrenched racism. I reiterated some of the children’s points: We could all make choices to celebrate diverse and accurate representations of people in our library, in public places like museums, in our schools, and in our communities. It’s important to think about whose voice is being heard, whose work is being seen, and to ask questions about fair or accurate representation. No doubt Simone was singing about more than racial representation. Yet we appreciated how the photos offered a concrete way for children to try to answer their own question.

The children loved this learning experience with thought bubbles. Christopher, a quiet student who pays exquisite attention to details, pulled me aside afterward. “Can we make people think again?” he asked.

“She Wants Justice”

Around this time, my colleagues and I were in the beginning stages of co-creating an inquiry-based dance with students in which they would analyze lyrics to a song before generating choreography. We thought we could refocus our attention on Nina Simone and take a deep dive into another one of her songs as practice. Earlier in the year, we’d listened to Fobia’s “Revolución Sin Manos” and the kids had a discussion about what “revolution” means: a big change. Simone’s 1969 song and the image on her album Révolution! were ripe for a learning experience based on perspective-taking. The song and album provided students another opportunity to contemplate Power and Change and the concept of representation that had emerged. We decided to show students the album cover first — a black-and-white photo of a pensive Simone with the song and album title emblazoned at the top in bright red font.

We made copies of the album cover for each table group and repeated the noticing and wondering routines we’d employed with van Raay’s protest photographs. We listened in as children asked questions about everything from “What does ‘RCA’ mean?” (which was written at the top of the album) to “Is she sad or maybe just very focused?” to “I wonder if there are sad or happy songs or a mix?”

Luciana swooped her finger across “Révolution!” with a flourish. “It’s bright, fancy letters,” she said.

“¿Por qué son letras rojas? [Why are the letters red?]” Kennedy wondered.

“Maybe it’s like sangre o una emoción fuerte o un mensaje importante [Maybe it’s like blood or a strong emotion or an important message],” Elle responded as her eyes widened and she melodramatically put her hands on the desk.

Before we gave children blank thought bubbles to fill with Nina’s thoughts, they had an opportunity to do a gallery walk to view what other groups noticed and wondered. Children saw they had similar questions and initial ideas about the album and song “Révolution!” Then, they individually worked on their thought bubbles.

Shane wrote: Yo creo que ella estaba pensando que va a cambiar el mundo para vivir en paz y para los demás y ella no va a parar. [I believe she was thinking that she’s going to change the world to live in peace and for others and she isn’t going to stop.]

Gia quickly generated four thought bubbles in the first person. One read: Yo pienso que otras cantadoras y muchos más van a ser inspirados por mí. [I think other singers and many more will be inspired by me.]

Fili tilted her head and pursed her lips; she was thinking about how not everyone had fair work. We had talked about access and opportunity as we read about Alma Thomas, Shirley Chisholm, Jackie Ormes, and other changemakers. “Se ve triste. Tal vez está pensando en las artistas de Nueva York o las mujeres que no pueden hacer muchos trabajos. Creo que ella quiere que todos tengan oportunidades justas. [She looks sad. Maybe she’s thinking about the artists in New York or the women that can’t do many jobs. I believe she wants everyone to have fair opportunities.]” When I returned to her table, Fili had written: No todos tienen trabajos justos. [Not everyone has fair work.]

There was a huge variety of ideas about “Révolution!” and the big changes Simone might be dreaming of and singing about. After completing their individual thought bubbles, Elle and Serene collaborated on a thought bubble that was surrounded by musical notes. “We wrote her thoughts as a song,” Elle said when I asked about the notes.

“Like she’s humming it in her head,” Serene added. I asked if we could all hear it. After a sheepish giggle, they agreed. Elle and Serene sang:

She means changes and she wants it.

She wants justice.

She’s angry.

She wants to be understood

and free!!!!

. . . and part of the free Black world!

Lilah stood up and clapped. Everyone followed. “She just wants to be represented like Jackie Ormes,” Serene explained once the applause died down. She wants Black women to be represented how they actually are — not in a fantasy or not low (gesturing toward the floor) and she wants to have the freedom for everyone to be themselves. That’s the revolución!” Serene made air quotes. Shane stood up and emphatically pointed to Serene’s profound truth.

Children were abuzz once we cued up the YouTube video version of “Revolution!,” which included Simone singing and playing with a band and backup singers and an assortment of black-and-white stills from the late ’60s.

Before listening, I asked the kids to remind us what revolution meant — a unified shout of “a big change” was their response. “It takes a lot of people power to make big changes,” I said. “As we listen to this song about big changes, I’d like everyone to think about who is being represented.” I wondered how the children would respond to the themes and discordant music at the end of the video.

“Did somebody bomb that building like Martin Luther King Jr.’s home?” Keaton, who had studied Martin Luther King Jr. and created a papier-mâché bust of him, burst out when a black-and-white image of a man standing in front of a bombed building appeared.

Jaxon was also examining the photos in the video. “They’re protesting. Look ‘Equality Now. Injustice. Segregation — like Sylvia Mendez’ school. It’s representing lots of different types of people who suffered.”

As children listened, many whispered, pointed, and bopped their heads. “They’re all together singing saying ‘Do take a stand,’” Valeria said. “Like stand up for yourself y los demás [and others]. Help people. Es como una representación de activistas — personas que usan su voz cuando otros no tienen una o cuando otros quieren que no digan nada [It’s like a representation of activists — people who use their voice when others don’t have one or when others don’t want them to say anything].” An image of a white police officer with an angry attack dog appeared and soon after the guitarist began a cacophonous riff that crescendoed along with the other instruments. Bright circles of light accompanied troubling tones. A close-up of drums was followed by Simone banging on the piano. A couple of children grimaced at the discord.

As the video ended, Javi waved his hands wildly. “¿Por qué es así la canción? [Why is the song like that?]”

“Es para despertar a la gente [It’s to wake people up],” Georgia said. “Es como (she shook fists) violencia, injusticia (and pulsed her hands outward), necesitamos cambio. No es bonito porque no es bonito [It’s like (she shook fists) violence, injustice (and pulsed her hands outward), we need change. It’s not pretty because it isn’t pretty.

“Vale, ¡qué mensaje! [That’s right, what a message!]” Valeria agreed. “¿Entendieron? [Did you all understand?]”

Her classmates nodded earnestly.

* * *

Students’ comments seemed to show they were starting to understand how individuals’ changemaking often connects to a broader struggle — ideally for justice. Of course, the definition of “revolution” as a big change did not get fleshed out in any detail. Yet listening to and learning about Nina Simone and other changemakers seems to have helped students connect the concept of revolution with justice.

As my teacher colleagues and I try to find what is urgent to our students, we plan this way: 1. Look at the Common Core and the Learning for Justice social justice standards. Find a great read-aloud or several that are relevant and related to the standards and a big idea we’re teaching (e.g., Mexican Repatriation, Japanese Incarceration, Black Lives Matter, the Land Back Movement, etc.). 2. Gather primary sources (interviews, songs, performances, photos, etc.) related to the read-alouds. Introduce routines for children to respond in small groups and/or individually to primary sources and create space for discussion. 3. Find a way for children to go public with their thinking — through dance, a protest, public service announcements posted via QR codes at school or in the neighborhood, fundraising, a community art project, etc.

A conversation at the end of our Power and Change unit continues to resound. Keaton was serious that day: “Change is hard. Some people don’t want things to change and some people do.” Georgia listened somberly, took a short sip of a breath, and offered us this truth: “El cambio es algo que hacemos juntos [Change is something that we do together].” This is what we had wanted to teach all year — change as communal action. As teachers and students, we grow and change minds and hearts — from ideas about accurate representation to whose voices matter. All revolutions happen in community. l

Resources

Learning for Justice Social Justice Standards

https://bit.ly/lfjstandards

Nina Simone Videos

“Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” live in London, 1968.

https://youtu.be/DtJzr1Wcy_s

“I Wish I Knew (How It Would Feel to Be Free)” live at Montreux, 1976.

https://youtu.be/-sEP0-8VAow

“Revolution” live video from an unknown recording session

https://youtu.be/gFBoKE9H3PA

Excerpt from the 1970 documentary Nina: A Historical Perspective where Nina Simone discusses the meaning of Freedom.

https://youtu.be/nPD8f2m8WGI

Changemaker Picture Books

Because Claudette

By Tracey Baptiste

Shirley Chisholm Is a Verb

By Veronica Chambers

Ablaze with Color: A Story of Painter Alma Thomas

By Jeanne Walker Harvey

Alejandria Fights Back! / ¡La lucha de Alejandria!

By Leticia Hernández-Linares

Sharice’s Big Voice: A Native Kid Becomes a Congresswoman

By Nancy K. Mays and Sharice Davids

No Voice Too Small: Fourteen Young Americans Making History

Edited by Lindsay H. Metcalf, Keila V. Dawson, and Jeanette Bradley

Jackie Ormes Draws the Future: The Remarkable Life of a Pioneering Cartoonist

By Liz Montague

Nina: A Story of Nina Simone

By Traci Todd

Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation

By Duncan Tonatiuh

José Feeds the World: How a Famous Chef Feeds Millions of People in Need Around the World

By David Unger

Amanda Gorman

By Maria Isabel Sánchez Vegara

Jean-Michel Basquiat

By Maria Isabel Sánchez Vegara

Pequeña & Grande Carmen Amaya

By Maria Isabel Sánchez Vegara