What Makes a Baby, Really?

Co-Creating Inclusive Resources About Human Reproduction with Middle School Students

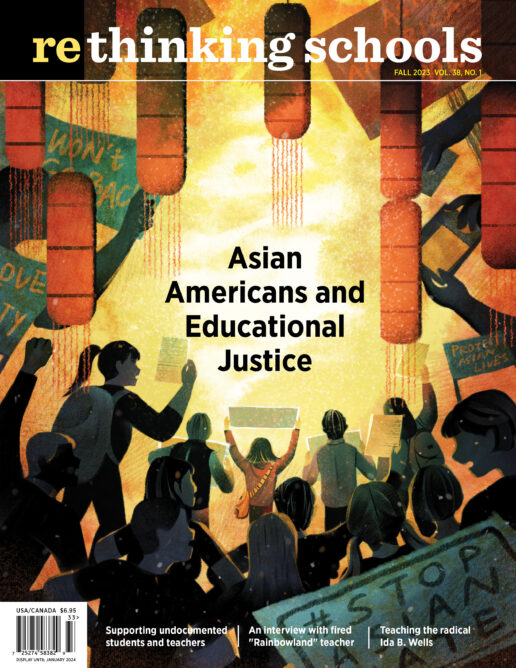

Illustrator: Ebin Lee

“Do you think it could be true?

That a scientist genetically edited a baby?” I looked up to see an 8th grader leaning on a pile of ungraded science projects on my desk.

“I think we’ll have to do more research to learn about the story. What have you heard about it so far?” We chatted for a few minutes, drawing some connections to previous learning and what we know about the possibilities and ethical boundaries of genetic manipulation in humans.

I was no stranger to these types of questions as a human biology teacher. The human body is inherently political, and reproduction brings up big questions for adolescents exploring their own family history, political views, gender identity, and sexuality. As an out queer and transgender middle school science teacher working in a liberal private school in Seattle, I felt supported by my administration and school community to integrate students’ questions about human reproduction, ethics, and genetics into the curriculum. I wanted my students, mostly from white, upper-class families, to feel informed and empowered to explore those questions for themselves, equipped with a foundation in factual, inclusive scientific understanding. I also knew, as a white teacher with similar social capital as many of my students, that developing a critical understanding of these issues as adolescents could help them become more engaged and politically active adults, using their privilege and power to advocate for reproductive justice.

The case study my student had brought to my attention involved assisted reproductive technology, including in vitro fertilization (IVF). In this procedure, eggs and sperm are united outside the body to create a zygote, then re-implanted into a uterus after a few days of development have occurred. Many people use IVF to conceive, including those who have lower egg reserve or sperm counts, those who cannot or choose not to carry their own pregnancy, and those using donor eggs and/or sperm to have children.

Human reproduction is not always taught in a way that includes the many ways people come into this world, and IVF is overlooked by nearly all sex ed curricula. Too often, human reproduction (and sexuality) is taught in a separate, non-academic class, and framed primarily around heterosexual penis-in-vagina intercourse and its relationship to pregnancy and disease. I wanted to find resources that would allow my 8th-grade classes to engage with human reproduction in a more universal way — a way that every student could see themselves in and that would provide a basis for rich conversations about reproductive technology and genetics.

Thankfully, I had at my disposal the fabulous book What Makes a Baby by Cory Silverberg. This children’s book was published in 2012 to much acclaim and excitement from folks across the spectrum of diverse families, caregivers, teachers, and kids. It tells the story of how babies come into the world in an accurate way without ever implying the gender(s) of baby creators, parents, or the relationship between those people. For example, many books about the origins of a baby talk about a mother carrying a pregnancy — however, many people are born to those who are not their parents (such as those born through surrogacy), or to men or nonbinary people who have a uterus and choose to carry a pregnancy. The book was a perfect way to introduce pregnancy and birth (including IVF) that didn’t involve inaccurate and dysphoria-ridden resources that link what gametes people make (such as sperm or eggs) and their gender identity or relationship to future genetic descendants.

The teaching of human reproduction does not often include the many ways people come into this world.

What’s Wrong with “Mother” and “Father”

Before we opened the book together, I needed to have an important conversation with my students. My dear friend Christine Zarker Primomo, another middle school teacher, started her units on genetics and reproduction with a norms-setting strategy around language that I wanted to try with my students.

I stood at the whiteboard, looking out at the 22 students in my classroom. “Today, we are going to be doing very important work. We are going to add a new word to the language we use in this classroom — and we get to create it, since English hasn’t come up with a word for it yet.”

I saw some blank stares. Students are rarely excited about vocabulary, let alone words that no one else uses.

“New people are made from merging a sperm and an egg. When you look in the genetics section of a textbook, you will often see diagrams that show genetic lineage that label the people who make those cells as “mother” and “father.” What might be some issues with that?”

James, a cisgender boy who often had a lot to share, responded, “Saying ‘mother’ or ‘father’ seems to be making some assumptions.”

I smiled. “Sure! Assumptions like what?”

Another student chimed in “Like that the people who make you genetically are your parents. I’m adopted, so while I have a genetic mother and father, they’re not the parents I live with.”

Eli, a transgender student, added on. “It’s also important to eliminate gendered language from the term, since not everyone who makes eggs is a woman, and not everyone making sperm is a man.”

“Great!” I turned back to the whiteboard and wrote a first bullet point for our list. “What are some words we could use instead for the people who make the sperm and egg that become a person?”

“What about ‘biological parent’?” one student asked.

I expected this based on conversations in previous sections. “I think we can be more creative — and more inclusive. Using the term ‘parent’ still implies a relationship that isn’t necessarily there. What other words could we use that don’t use that word?”

The students were quiet for a few moments. The first idea that emerged was “gene giver,” or “GG” for short. One student, as a joke, suggested “biological person” instead of biological parent, which got a few laughs. (I pointed out that we are all biological people, especially in this class!) Biological Life Transmitters (BLTs), DNA deliverers, Makers, Creators, the list continued. Finally, a student looked up as though a light bulb had gone off in their head. “What about ‘storks’? They bring babies!”

Once the list felt complete, students voted on their favorites. I read each name aloud and students raised their hand for as many of the names as they felt excited about using. In this section, “storks” won by a landslide. I wrote the word on the board as a reminder for us, along with the words chosen by my other three class sections, so I would remember to use each section’s chosen term.

“Now that we have this word, we will all need to help each other remember to use it. Any time you hear someone saying ‘mother,’ ‘father,’ or ‘parent’ in a situation where they really mean ‘stork,’ speak up!” It didn’t take long for the students to catch me at my own game — later in the period, I used “parent” to refer to a stork when discussing allele inheritance. A student said “Lewis!” without missing a beat, and in accordance with our class agreement, I said “Oops!” to acknowledge the mistake, and moved on.

Armed with our new language, we turned to the original text of What Makes a Baby, which is a colorful book aimed toward a target audience much younger than my teenage crowd. It never fails to amaze me how much of students’ “cool” exterior melts away when someone reads them a picture book. As I turned the page to begin the story, some students moved to sit on their desks or on the floor to be more comfortable. Some reacted with laughter to pages with images of cartoon sperm and egg cells to create a baby. On the last page when the book asks the reader: “Who was waiting for you to be born?” A chorus of students responded “Aww.”

“All right, y’all. It’s a good story, it’s true. And we can see how the author took the time to create a story that everyone could see themselves in. In fact, they never even used language that needed to be replaced by ‘storks,’ which is pretty cool. But it’s not exactly at an 8th-grade level. What needs to be added to get it there?”

“I feel like the book does a good job of being universal, but it doesn’t have a lot of detail,” one student responded. “Like, we’ve been talking about trans people, and surrogacy, and adoption . . . maybe it could talk more about those different things and explain them.”

Another student called out, “Talk about sex!” An uproar of laughter followed.

“I’m still confused about chromosomes and DNA and how they fit into the story. I think a book at our level should explain that and how it connects to a person’s storks.” I smiled, knowing that this was exactly the goal of the project I had in mind — for students to understand how genetic information is inherited in the most universal way possible.

“These are all really great ideas, friends. Thank you. I’m going to take these ideas and rewrite What Makes a Baby to better match the level we are at and help explain some of the details that we feel are missing from the text. In the next class, it will be your job to illustrate them.” Some students looked excited. Others looked terrified. “Don’t worry — you won’t be graded on how good your pictures look, just on how well they connect to the story.”

And so, What Makes a Baby: 8th-Grade Edition was born. I had decided to provide students with a base text, rather than having them write it themselves due to time constraints. While writing, I used inclusive language guidelines and help from friends to craft the text. For example, one strategy the AIDS Community Care of Montréal includes in their Inclusive Sex Ed Language Checklist is to focus on body parts rather than gender/sex terms: Instead of saying “women produce eggs,” say “ovaries produce eggs.” My colleague River Suh recommends moving toward descriptive language about frequency of traits, such as common, most often, or frequently, rather than using loaded language like “normal,” “natural,” or even “typical” (see Resources).

Throughout the year, we had worked on creating and using scientific diagrams, so illustrating the text felt like a nice capstone to showcase the ways those skills had developed since we had started in August. Images were an excellent way for students to externalize their thinking — they could clearly model processes and changes over time, focus on diagramming essential details to convey meaning, and familiarize themselves with the structure and function of body systems in a more comprehensive way.

Drawing Sparks Big Questions

The next day, small groups of two to three students huddled around tall lab tables. Some searched for images online, others discussed the core of the text they had been given. Some groups grabbed whiteboards to sketch out their ideas, others already had pencil on paper to outline possibilities. Using small groups was an intentional practice: I wanted students to process the information in a variety of modalities (verbal, visual, organizational), and also have a trusted peer to talk through these topics in a safe but flexible space. I was careful to put students together with those I knew they had a trusting relationship with, even if they weren’t best friends. As they worked, I circulated and asked occasional questions like “What is the most important part of your page to show readers? What is the most confusing part of the text for you? How could you clarify that idea in your image?”

Below are excerpts from the text that I created for What Makes a Baby: 8th-Grade Edition, along with conversations I had with student groups about researching and illustrating those passages.

Egg development — Before fertilization can occur, egg cells must mature. This happens in three steps. In the follicular phase, for most people who ovulate, hormones produced in the brain travel to the ovaries and stimulate the initial development of 15–20 eggs. Estrogen then limits the growth of all but one or two of those eggs to maturity in pockets called follicles.

The process of ovulation and menstruation is often overlooked and misunderstood in the science classroom. Each group assigned this page had riotous conversations about misconceptions they had about eggs, fertility, and menses.

“Wait — you mean the egg isn’t what causes bleeding? What is it then?”

“Why is it that so many eggs develop, but only one or two mature? Is that how you get twins or triplets?”

“But how is it that birth control can stop your period from happening?”

As much as possible, I redirected students to either the text they were given or to online resources to find the answers to their questions. We practiced online research about the human body throughout the year, so they knew places to start for reliable information, such as Mayo Clinic, KidsHealth, and Scarleteen. It’s an important skill for them to have in moments when they don’t have a trusted and informed adult to lean on for answers. One group was amazed that it was the endometrial lining, not the egg, that caused bleeding during menstruation. Another had no idea that there were so many different hormones at work in the process.

Sarah and Denise, two cisgender girls working as a team, created a diagram that showed the relationships between different parts of the body in each phase of egg development and menstrual shedding. The cycles were shown at multiple scales at the same time: organ-level, cellular-level, and chemical level. To this day, I don’t believe I have seen a clearer diagram in a textbook or online resource.

After an egg is mature, it can be fertilized by a sperm cell. Eggs and sperm both contain half of the genetic material in a human body cell. Once they combine, a zygote is created — a single fertilized egg with a complete and unique human genome.

Some of my favorite conversations in the unit focused on misconceptions about sperm. Many students had been exposed to the idea of a frenzied race to the finish line, even though most of the transit of sperm inside the body is controlled by cervical fluids and muscle contractions inside the body of the person receiving them. However, few if any of my students were aware that very few sperm made by a person with functional testes are considered “normal,” and the rest of the sperm have some kind of variation that can impede successful fertilization of an egg. (It’s a great way to compare and contrast the meiosis strategies of each cell type.)

This came up casually with one group illustrating this page. “Can you guess how many sperm produced by most sperm-producing people look like the textbook image you have in your minds?” I asked. They each guessed about 90 to 95 percent, wildly off from the actual number: 4 to 10 percent. They rushed online to look up images, and laughed riotously at pictures of sperm with two heads, sperm with two tails, sperm with giant heads, sperm with barely any head at all, and more. They drew a wide range of sperm types on their page. I saw a number of students stopping by to read that page in particular when the project was complete and hung up around the classroom.

Once an egg is fertilized, it starts to divide — really fast! Mitosis begins and the zygote becomes a morula, which is a ball of cells that some people think looks like a raspberry. A morula can develop in a variety of settings, including outside the human body. When fertilization happens in a lab, it is called “in vitro fertilization,” or IVF.

I had one tender conversation during this unit with a student who had heard things about the “quality” of embryos produced through IVF. When an embryo is selected for implantation in a uterus in the process of IVF, it is given a two-letter grade that is based on the appearance of the cells and outer layer of the developing embryo. This student knew they were conceived through IVF, and worried that they were not very athletic or strong because of their conception process. They wondered if an embryo grade could be related to the way they felt in their body as a young adult. We talked for a while about the wide range of human diversity, and although embryo grade does correlate to the success rate of a pregnancy, it has not been found to have any effects on the babies born as a result. It was a reminder of how important it is to create an open space for students to express concerns and questions, and how an inclusive curriculum can make a big difference in how a student conceptualizes their own history and experiences in the context of science and the broader world.

The longest amount of time a morula has lived in a lab is 13 days — that is because of an international rule that says you cannot allow a human to develop for longer than 14 days in a lab.

Questions of ethics and reproductive justice came up many times in the three-week unit. Discussions of IVF require considering when human life — and human rights — begin, and how to navigate challenging questions faced by scientists researching this subject. Considering the possibility of genetic editing and even genetic screening led to conversations about eugenics and the painful history of racist, ableist reproductive control.

In our unit on the cell cycle some months before, we had read excerpts from The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, including passages that described Western science’s persistent and ongoing lack of respect for Black life and well-being. In a video we watched that explained the concept of “designer babies,” one researcher discussed how important it was to prevent the genocide of disabled communities, including the Deaf community, through genetic editing and selection.

“But Lewis, don’t you think it’s better for there to be less suffering in the world?” James asked something that is no doubt on the minds of many outwardly abled students. I took a deep breath.

“I can hear what you are trying to say, James. But let’s step back for a minute. I know there are people in this room who have disabilities, even if they aren’t visible. There are many people near and dear to my heart who are disabled, and proud of who they are and what they’ve experienced, which includes their experience of disability. You didn’t intend to say this, but what can be heard in your statement reminds me a little bit of eugenics — deciding who is more ‘ideal’ or ‘desirable’ and choosing who gets to survive. While it’s good to use science to alleviate suffering, many disabled people would say it is not their disability that causes suffering, but rather the ableist way the world is set up to not meet their needs — including how science views them and treats them.”

The class was quiet for a few moments. Then, James asked, “So, do you oppose the right to abort a baby based on the results of genetic testing?”

Although I believe that each person carrying a pregnancy should have the choice of whether to continue that pregnancy or not, I was not prepared to speak to the complexity of the question James had asked, nor did I want my personal beliefs to take up so much space in the classroom that others would be uncomfortable sharing their own. I took a moment to decide how to respond.

“The decision to continue a pregnancy is deeply personal and unique to each person. I choose to not share my personal beliefs on this topic, but welcome you all to share your own beliefs, recognizing that we are not going to necessarily agree.”

Now, living in a post-Roe world, these questions seem more urgent. As reproductive rights are disappearing across the United States, I find myself increasingly called to speak out about my own beliefs of individual agency and the right to fertility assistance and safe, legal abortion. If I could go back to that classroom conversation, I would likely disclose more of my personal experiences and ethics, and express a conviction that both reproductive rights should be protected and the rights of the disabled community need to be lifted up. After all, it is often the disabled community who is most at risk of losing control over their right to reproductive self-determination, as history has shown. I would hope that my own vulnerability would serve to allow my students to do the same — though there are no easy answers to how to navigate those conversations in a way that will work for everyone.

As a transgender man who hopes to carry a pregnancy in the future, I have a deep and personal investment in inclusive, accessible, and legal reproductive health care. It is my hope that through this project, my students were able to better understand a more complete picture of how reproduction can happen. I also hope that by normalizing ways that the queer and trans community often bring children into their lives, I am opening space to understand and celebrate the many ways that people — storks, parents, and the humans they create together — create families.

* * *

We finished our book and read it out loud as a class. Our narrative was cohesive, inclusive, and supported students’ sense-making around how IVF functions in the larger picture of pregnancy and birth. Though the original text had come from me, the conversations interwoven into the narrative and construction of students’ understanding and engagement with these ideas meant that the story belonged to the whole group. In the following weeks, I saw students spend time walking around the room and learning from one another’s images and ideas. In the future, I want students to write their own text as well as create illustrations.

I hope that over time, more and more resources will become available for teaching students of all ages about reproductive science in an accurate and inclusive way — until then, I’ll be creating them alongside my students.

RESOURCES

What Makes a Baby? Reader’s Guide

A comprehensive guide for teachers, parents, and beloved adults who want to read What Makes a Baby? with a young person.

bit.ly/3YucwdT

The Macho Sperm Myth

This essay explores common misconceptions taught in sex ed that connect to the way gametes are often viewed through gendered stereotypes, and provides detail on what is actually occurring during reproduction.

bit.ly/47pgZCR

Scarleteen

An inclusive sex ed resource geared toward teenagers and emerging adults.

scarleteen.com

Inclusive Sex Ed Language Checklist

This set of language recommendations (and accompanying infographic) by SextEd can be a helpful guide for talking about reproduction, sexual organs, and identities in an inclusive way.

bit.ly/3QzrsFL

Infographic: bit.ly/3ORx2lJ

Talking to Kids About Science in a Gender-Inclusive Way

River Suh’s guide expands on the sex ed language checklist, using similar principles, to general terms often encountered in the general classroom.

bit.ly/3QQLSKL

Reproductive Justice Timeline: Forward Together.

This timeline explores major events in history connected to reproductive justice in the United States, including the disabled community, LGBTQ+ community, and communities of color. It is available in English and Spanish.

bit.ly/3QAbuLB

The Gender-Inclusive Biology Project

A website dedicated to curating free, science-based resources for educators and students co-creating biology education that is inclusive of the wide spectrum of diversity in gender, sex, and sexuality in humans and beyond.

genderinclusivebiology.com

BOOKS

Corinna, Heather and Isabella Rotman. 2019. Wait, What? A Comic Book Guide to Relationships, Bodies, and Growing Up. Limerence Press.

Loveless, Gina. 2021. Puberty Is Gross but Also Really Awesome. Rodale Kids.

Quint, Chella. 2021. Own Your Period: A Fact-Filled Guide to Period Positivity. QEB Publishing.

Silverberg, Cory. 2013. What Makes a Baby? Seven Stories Press.

Silverberg, Cory. 2015. Sex Is a Funny Word: A Book About Bodies, Feelings, and You. Seven Stories Press.

Silverberg, Cory. 2022. You Know, Sex: Bodies, Gender, Puberty, and Other Things. Seven Stories Press.

Simon, Rachel E. 2020. The Every Body Book. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.