What I Wish I Had Said

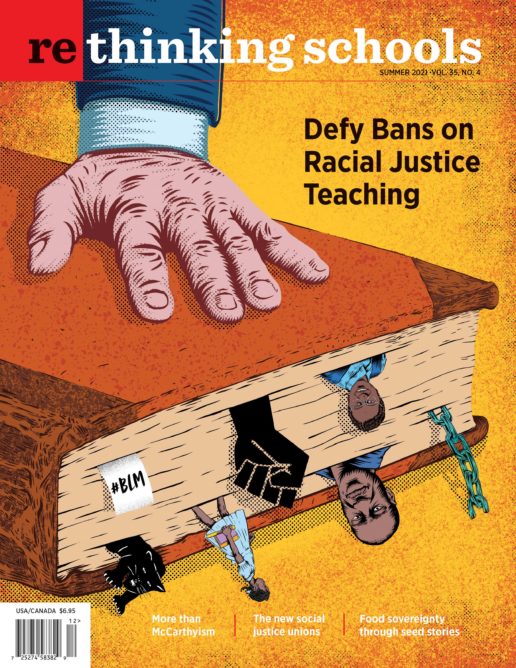

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

“Goodbye, everyone,” the music teacher sang out as she does every time my class leaves her room.

“Goodbye, Mrs. Smith,” 22 2nd graders sang back. It was my cue to walk them out. We did the quiet signal for the hallway, and a couple of kids gave the music teacher a hug on their way out. Akash walked by her and she called out lovingly, “Bye, Bobblehead!”

Mundane end of the day thoughts ran through my mind: Did I remember to tell Brian his mom will pick him up after school so not to ride the bus, what rotation is it for my after-school duty, what was that one announcement I was going to make . . . Wait. Did she just call him Bobblehead?

In my shock I froze.

And I said nothing.

Akash had arrived from India days prior. He had dark hair and a small frame. Our classroom community worked hard to welcome him to our school. A buddy in the class showed him around. We made sure he sat with someone at lunch and had a friend to play with at recess. He tried his best to use the English words he knew to communicate. His dark eyes intensely studied his new surroundings.

Akash consistently nodded his head from side to side when I spoke to him. It seemed that he was nodding left to right, right to left. He smiled often and I hoped he was starting to feel comfortable. Bobblehead? I thought of the plastic dolls springing their heads back and forth. I felt anger, sadness, and confusion.

I was in 2nd grade when I moved to Ohio from Japan. Growing up between two languages, I was told I could be a “bridge” between cultures. It felt like a gift and a burden. I have always felt responsible for explaining cultural misconceptions.

Now I needed to be this bridge at work. I had the EL credentials that gave me the “expertise” to express my concerns to a colleague. But I couldn’t find the right words to speak to the music teacher.

Our suburban district in Ohio was experiencing a shift. Students from more than 100 countries and 70 languages were represented in our schools. The new superintendent was changing the narrative of our diverse population from a challenge to our greatest asset. However, the staff members did not reflect the student population. I saw cultural divides between students and their predominantly white teachers.

More than half of my class is multilingual: English, Spanish, Hindi, Gujarati, Chinese, Serbian, Arabic. It was the classroom I dreamed of as a child where our collective immigrant background was part of our story and not what defined us.

I took pride in the community my class had created together. Had one of my students said this, my reaction would have been different. There would have been an immediate private conversation with the student. I would find out what the student said, why it was said, what it means, and ask how words impact others. It may have even turned into a whole-class conversation around how our words hurt people when we don’t mean to.

But the comment coming from a colleague made me speechless. Why?

What would I say to her?

Was I afraid to say something?

I decided to confirm the consistent nodding I saw Akash doing as a form of communication. My Google search revealed the gesture is common in India and most often means “I understand” or “yes.” There were many videos and travel sites explaining the nuances. It seemed to me that Akash was showing respect to his new teachers.

I worried I would upset Mrs. Smith. This teacher traveled. She sings songs in other languages. She teaches students about instruments from around the world. I knew she wasn’t trying to be hurtful. I thought if I raised my concerns with her, she would be defensive. I realized I was more upset about upsetting her than thinking about how I could speak up for my student.

Before I came up with a good plan, it was music day again. I picked up my students. They sang their goodbye song. As I walked them out the door, Mrs. Smith turned to Akash and said, “Bye, Bobblehead.”

I was not prepared to hear it again. I had moments to respond. The next class of students was eager to step into the music room. In the midst of the chaos of transitioning students, I said, “He’s nodding yes in his culture.”

As the last of my students walked out of the classroom, she responded. “Oh. Well, I just called him Bobblehead.” Her tone was neutral. Perhaps it was her turn to not know what to say.

It was a small step but I said something.

I never heard the word “Bobblehead” again.

Did my comment make a difference?

I felt unsettled that I didn’t say more.

In my ideal world, Mrs. Smith and I would sit down to talk. I imagined an uninterrupted heart-to-heart conversation over coffee, ending with an apology and a commitment to do better. We’d reflect together on our own communication styles and share the different cultures we bring to our classrooms each day. I visualized the conversation many times in my mind but it was always without sound. What would it sound like? What can it sound like?

If I’m expecting students to have hard conversations with me, I need to do the same with my own peers. This won’t be the last time I hear a comment that is hurtful. If it were me saying something inappropriate, I would want to know.

During my student teaching, I watched my mentor teacher have class conversations. She always stated the facts and I learned how to be very honest with children. I observed conversations she had with parents. But I never saw teachers working out issues with other teachers. Without modeling, it feels challenging to know what to do.

How many hours did it take for me to build community in order to have hard conversations with my students? Hours, days, months. In the classroom, I allow myself the space to make mistakes. It’s messy but I’m patient with my students and myself to grow.

As we build relationships with our students, we also need to deepen the relationships we have with our colleagues. Difficult conversations take time and practice. But the burden can’t rest on the “cultural bridging” done by individual teachers of color.

I felt unsettled that I didn’t say more.

The bridge needs to be broader. School, district, and union leaders need to commit to conversations, professional development, and policies that support culturally responsive and anti-racist teaching. Our schools must commit to richly incorporating immigrant backgrounds and cultures into the overall school culture. All teachers can commit to center equity and anti-racism in the work we do together.

Each time we speak up it gives us the courage to speak again. We need to model for our students how to be allies and work through injustices. Our actions, no matter how small, can have a large impact. I’m thinking about how I can state facts, ask questions, tuck away phrases, and make connections so I won’t be paralyzed in the moment next time.

“His name is Akash.” Is what I wish I had said.