What Color is Beautiful?

A kindergartner says he doesn't like his dark skin. His teacher grapples with how best to respond and finds a valuable resource in Nina Bonita.

Most of my kindergarten students have already been picked up by their parents. Two children still sit on the mat in the cafeteria lobby, waiting. Occasionally, one of them stands to look through the door’s opaque windows to see if they can make out a parent coming. Ernesto, the darkest child in my class, unexpectedly shares in Spanish, “Maestro, my mom is giving me pills to turn me white.”

“Is that right?” I respond, also in Spanish. “And why do you want to be white?”

“Because I don’t like my color,” he says.

“I think your color is very beautiful and you are beautiful as well,” I say. I try to conceal how his comment saddens and alarms me, because I want to encourage his sharing.

“I don’t like to be dark,” he explains.

His mother, who is slightly darker than he, walks in the door. Ernesto rushes to take her hand and leaves for home.

Childhood Memories

Ernesto’s comment takes me back to an incident in my childhood. My mom is holding me by the hand, my baby brother in her other arm, my other three brothers and my sister following along. We are going to church and I am happy. I skip all the way, certain that I have found a solution to end my brothers’ insults.

“You’re a monkey,” they tell me whenever they are mad at me. I am the only one in my family with curly hair. In addition to “monkey,” my brothers baptize me with other derogatory names – such as Simio (Ape), Chineca (a twisted and distorted personification of being curly, and even more negative by the feminization with an “a” at the end), and Urco, the captain of all apes in the television program, The Planet of the Apes.

As we enter the church, my mom walks us to the front of the altar to pray before the white saints, the crucified white Jesus, and his mother. Before that day, I hadn’t bought into the God story. After all, why would God give a child curly hair? But that day there is hope. I close my eyes and pray with a conviction that would have brought rain to a desert.

“God, if you really exist, please make my hair straight,” I pray. “I hate it curly and you know it’s hard. So at the count of three, please take these curls and make them straight. One, two, three. “

With great suspense I open my eyes. I reach for my hair. Anticipating the feel of straight hair, I stroke my head, only to feel my curls. Tears sting my eyes. As I head for one of the benches, I whisper, “I knew God didn’t exist.”

For Ernesto, the pill was his God; for me, God was my pill. I wonder how Ernesto will deal with the failure of his pill.

A Teachable Moment

I can’t help but wonder how other teachers might have dealt with Ernesto’s comments. Would they have ignored him? Would they have dismissed him with a, “Stop talking like that!” Would they have felt sorry for him because they agree with him?

As teachers, we are cultural workers, whether we are aware of it or not. If teachers don’t question the culture and values being promoted in the classroom, they socialize their students to accept the uneven power relations of our society along lines of race, class, gender, and ability. Yet teachers can – and should – challenge white supremacist values and instead promote values of self-love.

Young students, because of their honesty and willingness to talk about issues, provide many opportunities for teachers to take seemingly minor incidents and turn them into powerful teaching moments. I am grateful for Ernesto’s sincerity and trust in sharing with me. Without knowing it, Ernesto opened the door to a lively dialogue in our classroom about white supremacy.

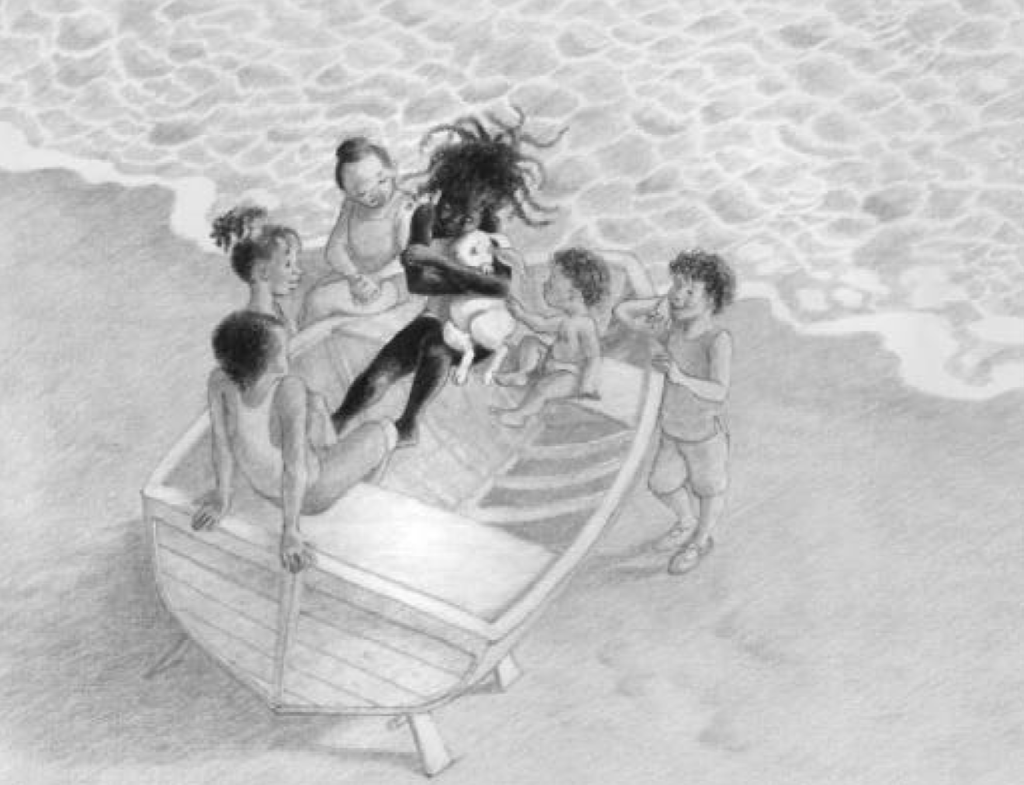

To resurface the dialogue on beauty and skin color, I chose a children’s book which deals with resistance to white supremacy (a genre defined, in part, by its scarcity.) The book is Nina Bonita, written by Ana Maria Machado and illustrated by Rosana Fara (1996, available in English from Kane/Miller Book Publishers). The book tells the story of an albino bunny who loves the beauty of a girl’s dark skin and wants to find out how he can get black fur. I knew the title of the book would give away the author’s bias, so I covered the title. I wanted to find out, before reading the book, how children perceived the cover illustration of the dark-skinned girl.

“If you think this little girl is pretty, raise your hand,” I said. Fourteen hands went up.

“If you think she is ugly, raise your hand,” I then asked. Fifteen voted for ugly, among them Ernesto.

I was not surprised that half my students thought the little girl was ugly. Actually, I was expecting a higher number, given the tidal wave of white dolls which make their way into our classroom on Fridays, our Sharing Day, and previous comments by children in which they indicated that dark is ugly.

After asking my students why they thought the girl on the book cover was ugly, one student responded, “Because she has black color and her hair is really curly.” Ernesto added, “Because she is black-skinned.”

“But you are dark like her,” Stephanie quickly rebutted to Ernesto, while several students nodded in agreement. “How come you don’t like her?”

“Because I don’t like black girls,” Ernesto quickly responded. Several students affirmed Ernesto’s statement with “yes” and “that’s right.”

“All children are pretty,” Stephanie replied in defense.

Carlos then added, “If you behave good, then your skin color can change.”

“Are you saying that if you are good, you can turn darker?” I asked, trying to make sure the other students had understood what he meant.

“White!” responded Carlos.

“No, you can’t change your color,” several students responded. “That can’t be done!”

“How do you know that your color can change?” I asked, hoping Carlos would expand on his answer.

“My mom told me,” he said.

“And would you like to change your skin color?” I asked.

“No,” he said. He smiled shyly as he replied and I wondered if he may have wished he was not dark-skinned but didn’t want to say so.

Carlos’s mother’s statements about changing skin color reminded me of instances in my family and community when a new baby is born. “Oh, look at him, how pretty and blond looking he is,” they say if the baby has European features and coloring. And if the babies came out dark, like Ernesto? Then the comments are, “çAy! Pobrecito, sali- tan prietito” – which translated means, “Poor baby, he came out so dark.”

I hear similar comments from co-workers in our school’s staff lounge. A typical statement: “Did you see Raul in my class? He has the most beautiful green eyes.”

It is no surprise that so many students must fight an uphill battle against white supremacist values; still other students choose not to battle at all.

Challenging the Students

In an attempt to have students explain why they think the black girl in Nina Bonita is ugly, I ask them, “If you think she is ugly for having dark skin, why do you think her dark skin makes her ugly?”

“I don’t like the color black,” volunteers Yvette, “because it looks dark and you can’t see in the dark.”

“Because when I turn off the light,” explains Marco, “everything is dark and I am afraid.”

Although most of my kindergarten students could not articulate the social worthlessness of being dark-skinned in this society, I was amazed by their willingness to struggle with an issue that so many adults, teachers included, ignore, avoid, and pretend does not exist. At the same time, it was clear that many of my students had already internalized white supremacist values.

At the end of our discussion, I took another vote to see how students were reacting to Nina Bonita; I also wanted to ask individual students why they had voted they way they had. This second time, 18 students said the black girl was pretty and only 11 said she was ugly. Ernesto still voted for “ugly.,”

“Why do you think she is ugly?” I asked, but this time the students didn’t volunteer responses. Perhaps they were sensing that I did not value negative answers as much as I did comments by students who fell in love with Nina Bonita. In their defense of dark skin, some students offered explanations such as, “Her color is dark and pretty;” “All girls are pretty;” and, “I like the color black.”

Our discussion of Nina Bonita may have led four students to modify their values of beauty and ugliness in relation to skin color. Maybe these four students just wanted to please their teacher. What is certain however, is that the book and our discussion caused some students to look at the issue in a new way.

Equally important, Nina Bonita became a powerful tool to initiate discussion on an issue which will affect my students, and myself, for a lifetime. Throughout the school year, the class continued our dialogue on the notions of beauty and ugliness. (One other book that I have found useful to spark discussion is The Ugly Duckling. This fairy tale, which is one of the most popular among early elementary teachers and children, is often used uncritically. It tells the story of a little duckling who is “ugly” because his plumage is dark. Happiness comes only when the duckling turns into a beautiful, spotless white swan. I chose to use this book in particular because the plot is a representation of the author’s value of beauty as being essentially white. I want my students to understand that they can disagree with and challenge authors of books, and not receive their messages as god-given.)

When I have such discussions with my students, I often feel like instantly including my opinion. But I try to allow my students to debate the issue first. After they have spoken, I ask them about their views and push them to clarify their statements. One reason I like working with children is that teaching is always a type of experiment, because the students constantly surprise me with their candid responses. These responses then modify how I will continue the discussion.

I struggle, however, with knowing that as a teacher I am in a position of power in relation to my young students. It is easy to make students stop using the dominant ideology and adopt the ideology of another teacher, in this case my ideology. In this society, in which we have been accustomed to deal with issues in either-or terms, children (like many adults) tend to adopt one ideology in place of another, but not necessarily in a way in which they actually think through the issues involved. I struggle with how to get my students to begin to look critically at the many unequal power relations in our society, relations which, even at the age of five, have already shaped even whether they love or hate their skin color and consequently themselves.

At the end of our reading and discussion of the book, I shared my feelings with my students.

“I agree with the author calling this girl Nina Bonita because she is absolutely beautiful,” I say. “Her skin color is beautiful.”

While I caressed my face and kissed my cinnamon-colored hands several times happily and passionately, so that they could see my love for my skin color, I told them, “My skin color is beautiful, too.”

I pointed to one of my light-complexioned students and said, “Gerardo also has beautiful skin color, and so does Ernesto. But Gerardo cannot be out in the sun for a long time because his skin will begin to burn. I can stay out in the sun longer because my darker skin color gives me more protection against sunburn. But Ernesto can stay out in the sun longer than both of us because his beautiful dark skin gives him even more protection.”

Despite our several class discussions on beauty, ugliness, and skin color Ernesto did not appear to change his mind. But, hopefully, his mind will not forget our discussions.

Ernesto probably still takes his magic pills, which, his mother later explained, are Flintstones Vitamin C. But I hope that every time he pops one into his mouth, he remembers how his classmates challenged the view that to be beautiful one has to be white. I want Ernesto to always remember, as will I, Lorena’s comment: “Dark-skinned children are beautiful and I have dark skin, too.”