What Catalina Taught Me About Inclusion

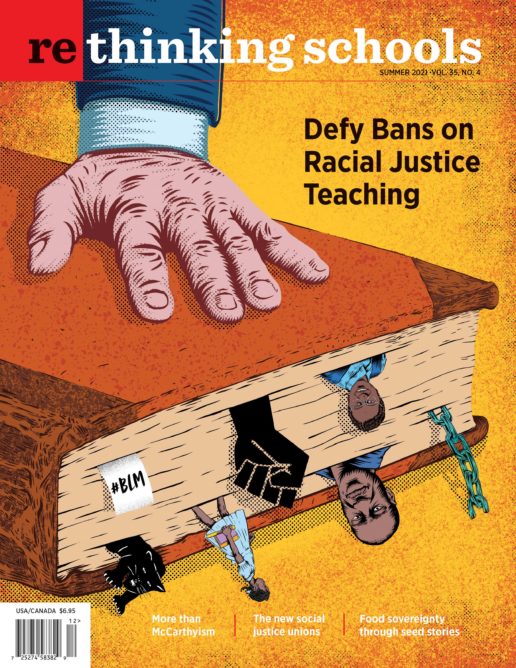

Illustrator: Simone Shin

Catalina uses an iPad to help her communicate. She pushes a picture button, such as a picture of a slide on her screen, and the iPad says the word “recess” aloud. She speaks sometimes, and the iPad adds to her communication skills. After school one day, Owen, a student in our kindergarten class without any documented disabilities, told his mom, “I was Catalina’s talker today. She didn’t have her iPad with her at recess, so I stayed with her to help her talk.” Many of the students in our class played tag games together at recess. I appreciated Owen’s desire to support his friend but saw this as a sign that I could build Catalina’s independence skills. Catalina’s mother asked her about recess to get her perspective. Catalina told her that she played with Owen, and he helped her talk to her friends.

My school has students with a wide variety of abilities. Our staff talks to students about the fact that “everyone is working on something.” Aware of my privilege as a white, able-bodied classroom teacher, I work to set this tone in our kindergarten classroom community. Our class includes students with various abilities and access needs — some use physical equipment, some have cognitive disabilities, some are on the autism spectrum. Some students in our class are emerging multilingual. There are assistants in our room for part of the day to support our classroom. We all have things to learn from each other and ways we can help each other. We teach that all of the kids are essential parts of our class and that some kids need breaks in other classrooms or “some extra help.” Kids find support with speech, socializing, counseling, physical environment adjustments, etc.

I took Catalina and Owen’s recess story as input for me. I realized that we needed to figure out a way for Catalina to communicate at recess, lunch, PE, when she did not have her iPad with her. I wanted her to feel comfortable interacting with her peers throughout the day. I talked with one of our primary grades special education teachers. Catalina was not a student on her caseload, but I knew the teacher had experience that would be helpful. She offered to create a picture card that we could safety pin to Catalina’s jacket so that Catalina could point to one of the four pictures/words as needed. We made several laminated copies and attached one with velcro to Catalina’s table spot as well. When she needed to quickly make a point (for example, to tell someone to stop), she could use the card instead of finding the right picture on her iPad.

I forgot to ask Catalina what she wanted.

Listening to Catalina

Catalina smiled at me when I introduced the cards to her. She and I practiced using them together. I observed her pointing to the “stop” picture a few times soon afterward. I caught her eye, and we gave each other thumbs-up. I helped clip the card to Catalina’s jacket before we left the room for recess and lunch. When we returned to class, the card was gone. I asked Catalina what happened to it, and she shrugged. I assumed it fell off at recess.

Over the next several days, I noticed Catalina ignoring the picture cards even when reminded by an adult. I also realized the cards kept disappearing. I asked Catalina if she liked the cards. She smiled and nodded but also looked away. I got the feeling she was telling me what she thought I wanted to hear. I rephrased the question to give her a choice: “Catalina, do you want me to make you new cards, or do you want to find another way to talk with your friends?”

Catalina said, “Yeah.”

I asked, “Which one? Find another way to talk with your friends?”

She nodded.

“Do you want a different tool or do you want to use your words? Or sign language?”

“Sign,” Catalina responded.

I thought I was helping Catalina by finding useful resources. My brief training in special education told me that the teacher could solve the problems. My classes never talked about inviting the student into the conversation. We rarely talked or wondered about student perspective when learning about differentiating curriculum and adapting the classroom environment.

I decided to teach the whole class additional simple sign language that we could use when communicating with each other. Our class had learned sign language when learning about letters. We had already learned to sign songs that we sang during our morning meetings and closing circles. During a class meeting, I reminded our class that we have many ways to communicate: words, facial expressions, body language, and sign language.

“Sign language is one way lots of people like to talk with each other, no matter their hearing status. We’re going to learn some more sign language together. Some people use signs and their voices, and others use signs with no voice. Both ways are great.”

I taught the students the signs for “play,” “stop,” “yes,” “no,” “help,” “please,” and “thank you” to begin. I didn’t know if this would ease Catalina’s communication, but I thought I could ask her for feedback and watch how she interacted after learning some useful phrases. I knew this time spent learning sign language could benefit the entire class. Listening to what Catalina wanted and needed without getting stuck on what I thought was best or thinking that she was obstinate opened up learning possibilities for all of us.

Building Solidarity

Students can understand with ease clear descriptions of what people need to live. I try to embed these conversations with suggestions to build empathy, such as “Some people use tools or equipment to write or move easier.” “Some people use songs to make waiting in line more joyful. Others use objects like Play-Doh or chewy necklaces to help their bodies feel calmer.” Directly acknowledging a difference or a strategy is sometimes more welcoming than speaking around it.

After the class was signing for a few weeks, I noticed Catalina using signs with me and in whole group discussions. Her participation had increased. Yet I noticed that some students continued to dismiss Catalina as an academic and play partner.

During our regular class meetings, we often talk about topics that affect the whole class and subjects that involve a single student. I carefully consider the impact of these conversations on the student we will be discussing and check in with them first to gauge their comfort level. I asked Catalina if we could talk about her use of sign with our class. I wanted to celebrate and directly acknowledge her use of sign language to build solidarity across accommodations.

One meeting, when Catalina answered a question in sign, I said, “I love seeing Catalina sign with our class. Do you like signing or speaking better, Catalina?”

Catalina smiled and moved her hands.

I said, “Sign language is an important tool for people who do not hear spoken words. It can also be an important tool for people like our friend Catalina, to help them use their voice, and for people who can hear and speak easily to communicate with more people.”

I saw kids nodding. Wyatt said, “My moms taught me signs when I was a baby before I could talk.”

“Yes,” I replied, “Lots of people use sign language for lots of different reasons. People worked hard for laws like the Americans with Disabilities Act so that Deaf students can use American Sign Language in schools. Some hearing people sign to communicate with Deaf people. Some hearing people use sign language instead of talking.”

Efrem pointed to the cube seat that he used when we sat on the carpet. “Efrem, do you want to say something about your seat?”

Efrem quietly said, “It’s like my chair.” Efrem’s cube seat sits on the floor and supports his back and sides to help him sit reinforced on the rug. This way, he can gather on our carpet for read-alouds and class meetings along with his classmates.

“Can you tell us more?”

Efrem said, “Well, I use this chair. Lots of kids don’t. But it helps me sit until my body gets stronger.”

“Oh, are you saying that you use a tool that helps you, just like sign language is a tool that helps people communicate?”

I wanted students to see that there was solidarity across abilities.

Efrem nodded. I wanted the students to see that there was solidarity across abilities. Efrem related to Catalina in their use of accommodations. Another student uses a slant board to help them write. Still other students use chewy necklaces to put their oral sensory needs at ease.

Kristel said, “What about my pencil? It helps me!”

“Yes, your thicker pencil helps you write and draw. We have lots of tools that we use!”

A disability is not a problem or something to fear. I try to create an environment where we can talk about each other’s equipment, needs, and adaptations openly and respectfully. I ensure we have various tools available for students to use when they prefer or when suggested. I encourage students to ask questions about each other with a sense of curiosity. Students reply as experts and share their knowledge about their bodies and equipment.

When we create environments in our classrooms where everyone has a voice, we begin to normalize a compassionate society. These conversations can build interdependence. And with time, this “helping each other,” the connection among people choosing to support each other, will feel expected. As students mature, I hope they question systems that exclude people and hold more inclusive expectations.

As an educator, I grow as well when I listen to my students, ask them what they need, and support their interests. Catalina taught me the importance of creating a space for students to advocate for their own needs and preferences.

Asking students what they need is crucial.