“We’re Just People Who Don’t Want to Be Killed”

A piece of our worth was stolen on Jan. 6, 2021. A mob brandishing the flag of the Confederacy as well as the campaign flags of the outgoing president stormed into the Senate Chamber.

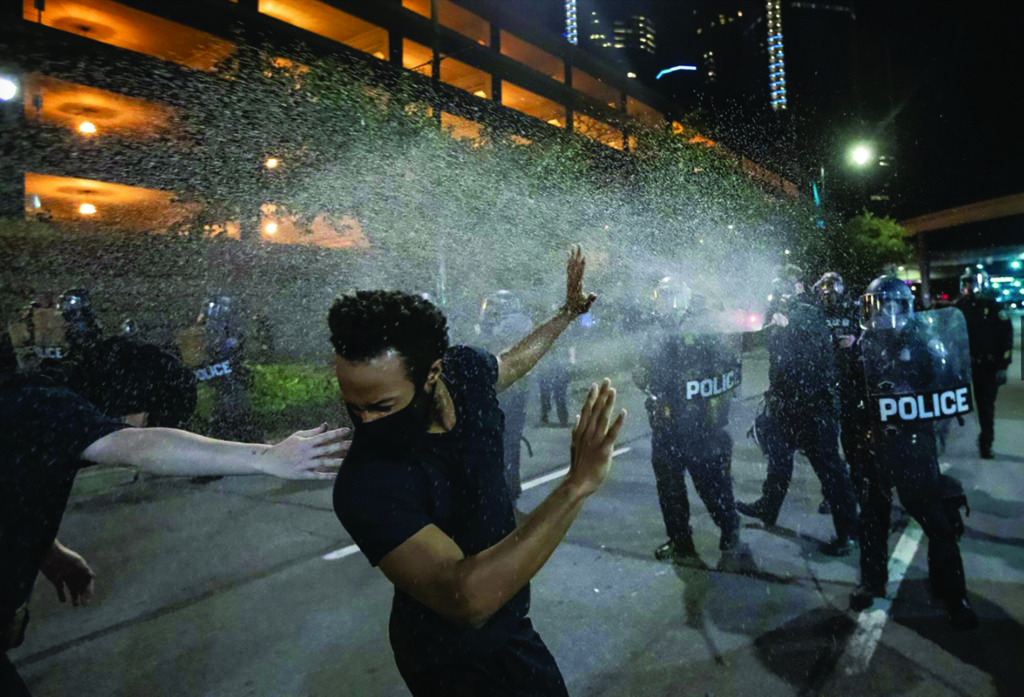

The trauma of seeing a respectful treatment of white insurrectionists on the heels of such hateful maltreatment of Black Lives Matter demonstrators in 2020 ambushed our homes through our televisions. We witnessed the audacious display of white privilege in the halls and on the steps of our U.S. Capitol during an attempted coup. This act of treason was simultaneously an assault on democracy and an attack on the souls of Black people.

And more personally, it was an attack on the soul of my son.

As Jamaal, 22, and I watched the coverage of the unfathomable, I noticed the quickening of his breath, the trembling of his hands, and finally an agonizing outburst: “We’re just people who don’t want to be killed!” With tears of fury and frustration, he stormed to his room. Without conversation, I understood to the depths of my own soul all of what came over him. Jamaal was inconsolable at that moment.

Unfortunately, seeing white people free to be so casual and unafraid of law enforcement after committing atrocious crimes isn’t new for Black Americans. The recognition that America doesn’t value the lives of Black people was immediate because the trauma lives in our memory and in the cells of our bodies. We have seen it before and over and over again. We saw it in the arrogance of the men who murdered Emmett Till (falsely accused of whistling at a white woman). We saw it in the joyful family picnics under the swinging Black bodies hung in the trees (many lynched for nothing more than being Black). It was in the celebratory smiles of the officers who beat Rodney King (drunk driving). It was in the smirk on the officer’s face as he was killing George Floyd (alleged counterfeit $20 bill).

For generations, the shadow of racial hypocrisy has perpetually loomed over the intersectionality of being both Black and American. In the words of Bettina L. Love in We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom, “Mattering has always been the job of Black, Brown, and Indigenous folx since the ‘human hierarchy’ was invented to benefit whites by rationalizing racist ideas of biological racial inferiority to ‘those Americans who believe that they are white.’” I fully understood the repeated exhibit of America’s racial hypocrisy is what shook Jamaal’s sense of “mattering.”

When he’s ready and emerges from his room, I will remind him why he matters. I will remind him that he inherited my affinity to speak up for the marginalized, stand for the disenfranchised, and embrace those who have been otherized. I will remind him that his ability to clearly see the racial hypocrisy humanizes him. I will remind him that as a young Black man, he represents the resilience of a people who know the potential of America’s liberation when equity is afforded to all. I will remind him that when he sees injustice, it is a call for him to contribute his thoughts, strengths, and abilities.

This is how you fit in the world, Jamaal.