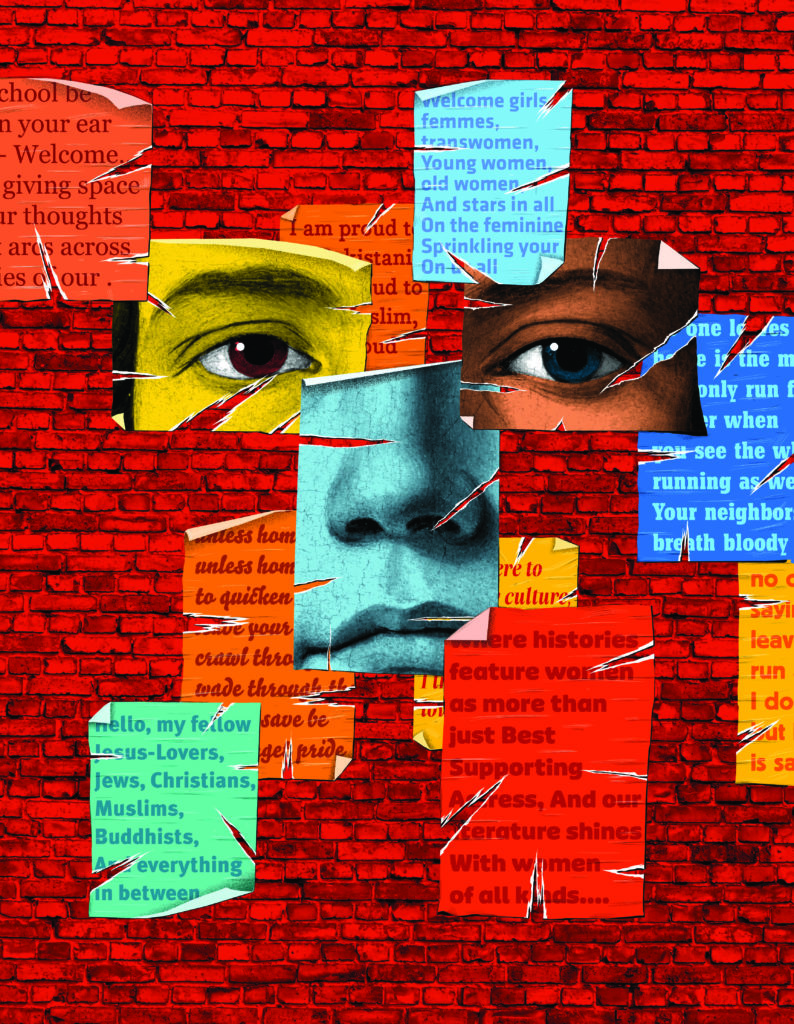

Welcome Poems Trump Hate

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

“Gender-neutral bathroom at progressive Portland high school tagged with death threat”

“Racist slurs written on Lake Oswego High School bathroom walls”

“Fed up with anti-Latino sentiment, hundreds of Portland high schoolers leave class”

Headlines like these filled page after page of search results, making my quest for articles about hate speech in local schools disturbingly, though not surprisingly, easy. Earlier that week, a group of us teachers called a meeting with our principal, pushing for a schoolwide response when nooses, white supremacist propaganda, and “It’s alright to be white” posters were found around our high school’s campus where about 75 percent of students are white. I first heard about it during a lunchtime Black Student Union meeting. Naima spoke up first: “I was down by the bus stop and I saw another ‘It’s OK to be white’ sign.” “Yeah,” Braden added, “I saw one of those, too. It’s some, like, internet thing.” I immediately grabbed my phone and started Googling. I found out that the slogan and campaign started on 4chan (an online alt-right message board) and became a national white supremacist offline trolling campaign.

After talking to more students and staff and uncovering a rash of other posters, graffiti, and even more nooses violating our spaces, a group of teachers called an after-school meeting with administrators to demand public acknowledgment, better methods to report hate speech, and lessons for every classroom. More than 20 of us showed up, and we won our demands. Many teachers then developed their own lessons or used a staff-created schoolwide climate lesson about identifying and stopping hate crimes. This activist poetry lesson is part of my classroom-level effort to talk back to hate speech in our schools.

I first introduced this lesson to students early in an immigration unit. We did this lesson while reading The Book of Unknown Americans, a novel by Cristina Henriquez that weaves together tales of a diverse group of Latinx and South American immigrants as they seek safety, education, political freedom, love, economic security, and hope.

To kick off the lesson, I asked students to visualize a place where they felt at home, somewhere safe and welcoming. “Close your eyes or let them rest softly on your desk,” I said, and the class fell quiet faster than I expected. “Now go to a place where you feel at home. In your mind’s eye, look around this place. What do you see?” This guided visualization helped them think about the comforting and positive imagery that they would later use in their own poems. It also reminded them of the value of having somewhere they can be accepted and loved for who they are. I asked students to share out where they went and why it feels like home.

“My happy place is the soccer field,” Jonas said. “We are like one big family and I love being outside.”

“I imagined the family parties we have at my grandma’s house,” said Esmerelda. “My family and I are all together and everyone is talking and laughing. We just eat and hang out with all the cousins and everybody.”

“All right, keep these places in your mind and heart today while we read and write some poems about the idea of home and places we feel safe. Some people might not have a safe place or a home right now, and it’s important that we hear from them. The poet Warsan Shire is going to start us off,” I said.

Next, I distributed copies of Shire’s “Home” and asked students to listen to a YouTube video of the poet reading her work while they followed along on the page. In “Home,” the speaker is a refugee chased from their home country by violence, making a laborious journey “in the belly of a truck” and across dangerous waters, only to be threatened and scorned in the place they finally arrive to seek asylum.

The class fell silent as Shire read:

No one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark.

You only run for the border when

you see the whole city running as well

Your neighbors running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats.

They shivered when she recalled a childhood crush “holding a gun bigger than his body,” and when her voice cracked as she reminded us that “No one wants to be beaten, wants to be pitied. No one chooses refugee camps.” The mood in the room was noticeably solemn by the poem’s end as Shire’s words stirred their hearts:

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

unless home told you

to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans

drown

save

be hunger

beg

forget pride

your survival is more important

no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying

leave,

run away from me now

I don’t know what I’ve become

but I know that anywhere

is safer than here.

In the quiet, I then asked students to read a second time on their own, marking powerful lines and poetic devices before sharing with a partner.

“What stood out to you?” I asked, and hands floated up.

“When the poet talked about putting her children in a boat, I saw how this was really out of her control,” Abby said. “She didn’t want to leave.”

“The list of insults that she hears are horrible,” said Malcolm, calling us to the litany of racist, vitriolic comments an immigrant might hear in a receiving country, each line a punch to the gut. Students also noticed Shire’s personification and powerful imagery.

This poem helped advance the discussion about the complex relationship between immigrants and home while also addressing the xenophobia and racism that hurt many of our students and community members, not just those in the fictionalized world of the book we had been reading.

“So today we are thinking and writing about the idea of being welcome and safe,” I said to students. “We’ve heard from the characters in our book and now from Shire, but I want to bring this issue home. You are now going to read a local news article about instances of hate speech in our community.”

>> Click here to subscribe to Rethinking Schools — 1 year for just $22.85 <<

Students moved out to jigsaw three local news articles that described instances of hate speech and hate crimes in our local schools. I asked them to note who was targeted, what perpetrators did to exclude them, and what people did, if anything, to fight back against the injustice. This helped get them thinking about who might feel unsafe or unwelcome in schools if they had not themselves been targeted. It also helped us uncover what needs to be addressed through our own poetry and actions.

“Do you think things like this happen at our school?” I asked.

The first to speak up resisted the idea.

“I don’t really think so,” said Chad. “This is a pretty friendly school and mostly people leave each other alone.”

“I actually don’t feel comfortable speaking for others,” Margot added. “As a white girl, I don’t get targeted, but maybe other people do.”

Cue Alton, a member of the Gender and Sexuality Alliance, who said, “I have a lot of friends who are trans who can’t even use the gender-neutral bathrooms here because of all the vandalism and disrespect. It’s humiliating for them that they can’t even get the same rights as everybody else.”

I wanted the discussion to help move students who think “This doesn’t happen here.” It was also an opportunity for me to tell students about incidents from our school that they may not have known about. After a few more students spoke, I told them, “In the past few weeks, teachers and students have reported nooses and white supremacist propaganda around our campus. This is deeply troubling and makes many of us feel unwelcome and unsafe.”

After debriefing more as a whole class, I asked students to make lists of times they personally felt unwelcome at school, plus other groups who might feel unwelcome or unsafe in our schools, using what we had just discussed and examples from The Book of Unknown Americans. For the first part of the list I told the story of being the new kid and asked students to write down ideas for two minutes. For the second part of the list, we drew from “Home,” the news articles, and our class novel. They shared their lists in small groups to continue brainstorming. We made a class list after.

“I bet the students with disabilities who work the coffee shop downstairs sometimes feel excluded. They are so isolated down there,” offered Jane.

“Yes,” I said, “and probably many students who have any type of learning or physical disability could feel left out or weird at school. Let’s add that, too.”

Trent added, “I think sometimes people make fun of the kids that play Magic: The Gathering or Dungeons & Dragons.”

“A lot of kids of color feel unwelcome here or just not represented because this is a really white school,” said Samiah. I added their thoughts to a list on the board as they called on each other to keep the ideas flowing.

“Kids who maybe don’t have the coolest shoes and stuff, like who come from a poor family,” said Junior. I wrote down students living on low incomes and took a couple more hands. When we had a good exhaustive list, I handed out the example poems.

Next we examined models written by me and my colleague Jessica Loomis, who developed this lesson with me. My own poem calls in women to an imagined school that is all about woman wonder. I performed it for students:

Welcome girls, femmes, transwomen,

Young women, old women,

And stars in all places

On the feminine constellation,

Sprinkling your stardust

On us all.

Let this school be a poem in your ear

Pulsing — Welcome . . .

Teachers giving space

To let your thoughts

Trace hot arcs across the

Galaxies of our classrooms.

Where histories feature women as more than just

Best Supporting Actress,

And our literature shines

With women of all kinds . . .

After looking at our models, I asked students what they noticed and what we lifted from Shire to make our poems sing. I pointed out any powerful images they missed that gave the poems a message of praise and togetherness. At this point, I let students know they will be writing a Welcome Poem to a group of their choice, and that we will hang them in the halls as a collective response to the hate we recently saw in our community.

Like any good lesson, this one elicited pushback from students, helping me see where I need to give them more support or more freedom. When I made the explicit connection between this project and the instances of hate speech at our school, Eric said, “These poems aren’t going to make a difference! People are just doing this for attention, and this isn’t going to change their minds.”

“Yeah,” Matt agreed. “People just want to be shocking. This kid in my 8th-grade class drew swastikas all over everything just to get a rise out of the teacher.” Many students agreed with this, nodding and murmuring, citing teenagers’ drive for rebellion as a potential cause for the nooses and hate speech.

“OK, I hear that, but does that mean we should just ignore them?” I asked. “What do you all think? Will ignoring the problem make them stop? How do you think the targets feel if everyone pretends it is not happening?”

In one class, Sofia shared that “I think we can see from what we are learning about in U.S. history that not talking about a problem doesn’t make it better. Ignoring racist acts doesn’t make them stop. People have to work together and stand up like Black Lives Matter is doing.”

“I think that if we pretend it isn’t happening, the targets might think no one cares,” offered Jamison, “and that’s messed up.”

In another class, Jenna said, “This isn’t a welcoming place!” She was worried that these poems were just another shallow showing of faux-support for students, another ineffectual adult response to student pain, and, ultimately, a farce. Where I hoped we were doing activist art, she saw the poems as a kind of denial of what really happens and continues to happen to students.

“I’ve never felt unwelcome at school,” another student shared. “How am I supposed to write this?” To that, Antonia said, “Yeah, but we can’t just sit back and do nothing. We can at least try to write something that would make someone else feel like they belong.”

Comments like these encouraged rich discussions in each class through which we grappled with what power we did and didn’t have as individuals and as a community. We talked about where schools go wrong, critiquing some of the lessons students are made to do that feel forced and decontextualized. Classes also surfaced the teenage brain, the impact of media and our current presidential administration on the frequency of hate crimes, peer pressure, and the difficulty of standing up in the moment, particularly when a friend is telling an offensive joke.

After this discussion, some students decided to write their poem as more of a talkback to an unwelcoming situation at school, highlighting the problem more than envisioning a new space. The rest then chose a group to welcome in their poem and make a list of things that would make that group feel welcome.

Students sometimes get stuck here, staring down at blank paper with squished faces, so I find it helpful to tell the story of drafting my poem, telling them how “I wanted to address graffiti, dress codes, school curriculum, and athletics — specific things I’d seen and heard that made me feel unwelcome as a woman at school. So, I asked myself, ‘What would young women need to see and hear to feel more welcome?’ That helped me come up with things like books that include women and girls getting more space to share their ideas in class. What about your group? What kinds of things would they see and hear to make them feel more welcome in our school?”

“We could have flags on the walls for different countries and groups. Mr. Nostrand has a pride flag and Ms. Potter has flags from a lot of countries students emigrate from,” offered Braden.

Alton chimed back in: “Like I said earlier, trans students could have private bathrooms in every hallway just like everyone else.” Conversation like this helps move them forward with specific nouns, verbs, and images to add to their own work.

After a few minutes of listing, we went back to the lines, images, and devices from the model poems that they could use as jumping-off points. I asked them to write the first draft of their welcome poem. They drafted for about 20 minutes in class, sharing with a partner, and the best stanzas were read aloud to the whole class at the end of the writing period. Hassan wrote a poem welcoming religious students to our halls:

Hello, my fellow Jesus-Lovers

Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists,

And everything in between,

Whose Bibles and Torahs are camouflaged as chemistry textbooks.

Let this school be your mosque, Holy, safe.

Where quotes from Gandhi, Confucius’ words of wisdom, And Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John’s stories flow like water down the Ganges . . .

Let this school tell a story of a thousand years, Of hope and worship, Spreading like wildfire across this world that was created in a thousand different ways.

Where you can believe in anything, A place where you can lay down your rug and close your eyes, Where an ant can carry an elephant, And a dodo can ride a horse.

Where anything really can be anything, And nothing is how it seems.

Kate borrowed a popular hook from the world of slam poetry when she wrote:

Dear young lgbt+ people:

You are valid.

No one can put you down or tell you you deserve to burn.

You are a blossoming flower

Not a growing weed.

Dear young lgbt+ people:

You are valid.

No one can put you down or tell you you deserve to burn.

You are a blossoming flower

Not a growing weed.

Dear young lgbt+ people:

These halls may seem scary

A mysterious and intimidating forest where anything could happen

But there is a clearing

A grassy field of acceptance

Where you can feel safe . . .

We returned the next day to revise, share again, and submit our poems.

To extend this into further activism, students could have mined their own poems for other meaningful actions to take and begin working on them as class projects. For instance, in my own poem, I mention the lack of strong female-identifying characters in humanities courses. My project could be to lobby for new novel sets in the district multimedia library or to develop a lesson or unit for my 10th-grade American Studies class that features wild and wise women.

Students might find they need a new club, a prayer room, a meeting with district officials, or a restorative justice circle to address what’s leaving them feeling unwelcome and unheard. Another thing students can and should do is take part in hanging their poems around the school or in a display outside the classroom so that the writing can bless passersby with a bit of praise. This was the idea I had pitched to my students at the outset of this assignment.

On the first Monday after spring break, I made the snap decision to print off the poems — without names — and see if students would be willing to hang them around the school at the start of first period, even without administrative approval. There are times to get approval, but it felt right to consider making this a demonstration of students taking community healing and action into their own hands, just like the perpetrators of the hate crimes had done in the weeks prior. I also was concerned that administration would say no, further stalling a healing, constructive response and perpetuating a systemic legacy of inaction in the face of hate speech and hateful vandalism.

I opened class by letting students know I had read and fallen in love with their poems over the weekend. “I got kind of a wild idea this morning,” I said. “I know we intended all along to post these around school. Do you think that we should just do it now? Like, to welcome everyone back from break? Maybe some students aren’t feeling so excited to come back here after everything that’s been going on and this could help them. What do you think?” With plenty of head nods, some “Yeah, Ms. J’s,” and a few “Whatevers,” the class agreed that my plan seemed like a good one. Many were energized by the fact that this was technically against the rules, something akin to a flash mob that would hopefully generate some buzz among students and staff, potentially leading to further dialogue and action around the hate incidents.

Before they left to hang their poem, we talked about whether the action was meaningless if the poems were torn down (no) and creative hiding places for the poems (many). I also asked them to imagine someone’s day being made just a tiny bit brighter on seeing a positive poem about them in the hall at school. I asked students where mine might fit well, and they shouted “Girls’ bathroom!” “Locker room!” and “History class!”

I hoped students might take my suggestion to read the poems while searching for the perfect place to put them, using the content to place them just where they would be needed, savoring lines like this one from Lars’ “Ode to Loners”:

To those who choke on their tears,

Of loneliness before they sleep,

With recollections of wandering aimlessly at lunch,

Sitting in the back without a friendly face in sight.

I wondered what Hamad’s poem about being an exchange student from Pakistan would spark in a student when they read:

I came here to share my culture,

I wanted to break the stereotypes,

I tried to spread love and peace,

But I was bullied by strangers,

Called a relative of Osama bin Laden,

Presented as a terrorist person.

I want to tell them that

Not all five fingers are [the same],

Not all Pakistanis are terrorists.

I am proud to be Pakistani,

I am proud to be a Muslim,

I am proud to be here . . .

I armed students with blue tape and a random poem from another student, sending them out to find the perfect place to hang it.

I felt justified in bringing this idea to students because it was clear from our staff-level and classroom conversations that students wanted to take some kind of action, but weren’t sure exactly what. Many students expressed frustrations with adults failing to bring ideas and failing to act. In the future, I will take time to engage them even more in the question of what to do with the poems, but in this case it felt appropriate to lead them a bit more.

By the end of the day, building administrators had taken down most of the poems because they lacked the stamp of approval from the front office. Others were torn down by students. But a few teachers kept them on the outsides of the doors or in their classrooms where they still hang almost a year later. Some hid for weeks on the inside doors of bathroom stalls or camouflaged in clusters of other signs. Teachers in my hallway dropped in for a fist bump, a thank you, or a question about the poems for weeks after the action. Despite the ones that were torn down, I still think this was a valuable experience, and later, administrators offered to make a permanent space for a display of selected poems, a project I turned over to students who were excited about the idea. Knowing this poetry lesson will be in my pocket for some time, I also look forward to seeing how this project evolves with student input about how and where our poems should be shared with the community and what else we can do when hatred and violence bubble up again.

As a teacher, I cannot stay silent when harm is done in my school. Doing so sends the dangerous message that I either don’t notice or don’t care when our kids experience injustice, when they are the targets of the very systems I am teaching them to struggle against. In my own classroom, I ask students to question the status quo, learn from past activists, talk back, and find hope. I want students to know that with our words and actions, we can reject silence and instead shout out our true values: inclusion, allyship, respect, and justice.

The power of poetry to name problems, to praise beauty, and to open hearts is undeniable, but we cannot stop there. We need to continue this work outside of our classrooms as well, including all those who rely on our schools for safety, sustenance, and hope. We also need to listen to students whose experiences of schools are hurtful and negative, seeking ever-more meaningful ways to make our schools truly welcoming.