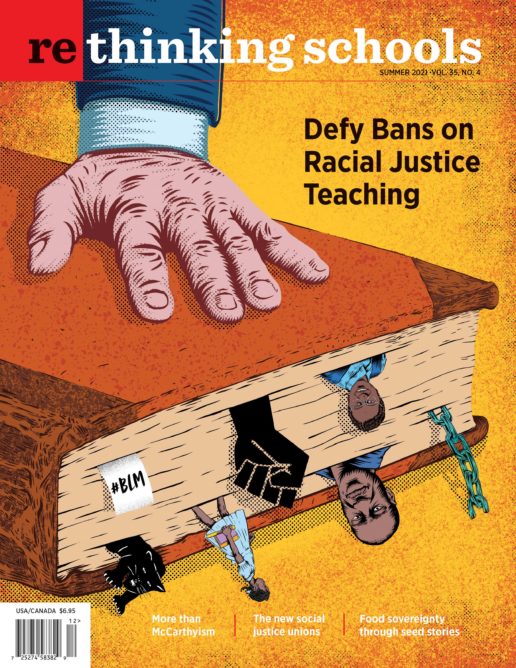

Voting for and from the Margins

Reimagining Electability Through Poetry

“What do almost all U.S. presidents have in common?” I ask one afternoon at the start of class.

I have students open their notebooks to brainstorm a list of characteristics to see what patterns we notice. “For example, all U.S. presidents have spoken English. Think about all of the different identities we’ve talked about this year.” I enumerate them, pausing after each one to give writing time: “Consider race; class; gender; sexuality; religion; disability.”

Students’ lists grow. “What have you got?” I ask.

Kiara says, “They’re all old white men. Except Obama!”

“That’s three right off the bat,” I say. I write up “old,” “white,” and “male” on the board. “Not counting Barack Obama, who was mixed-race, and John F. Kennedy, who was in his early 40s when he was elected, you’re exactly right.”

Nic offers, “They’re mostly rich.”

“Yes, Nic, excellent.” I write “rich.” “Can anyone think of an exception to this one?”

“Wasn’t Abraham Lincoln born in a log cabin or something?”

“You know, I think he was.”

“Have they all been Christian?” Trista asks.

“Protestant, even,” I say. “With one exception. He had to give a whole speech about it.”

“Isn’t that also JFK?” Emma says. “He’s Catholic, right? My vovó has a framed photo of him next to Jesus in her house. She’s, like, super Portuguese.” This earns her a few nods.

Kiara jumps back in: “They’re all straight.”

“As far as we know,” I say. I add “Christian” and “straight.”

“They were all born here,” Lisbeth points out.

“And weren’t a lot of them in the military?” Tyler asks.

“Perfect,” I say, completing our list, which we will circle back to for inspiration later.

“It’s like we only ever color with the same crayon,” Trista says, ever an artist, “even though we’ve got a whole box.”

“It is, isn’t it?” I say. “And why do we do that? Does it have to be that way? Today, we’re all going to think about who we’d really want to be president, if we could choose — like, really choose. To start, we’re going to read a poem called ‘I Want a President.’”

* * *

In 1992, decades before the Trump administration’s failed response to COVID-19, activists were confronting federal complacency in the middle of another pandemic. In the United States, HIV/AIDS was killing Black Americans and drug users at disproportionately high rates and altogether decimating the gay community. 150,000 Americans had officially died, the count still climbing. While Ronald Reagan stewed in a thick soup of his own inaction, groups like the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) fought back with radical direct action.

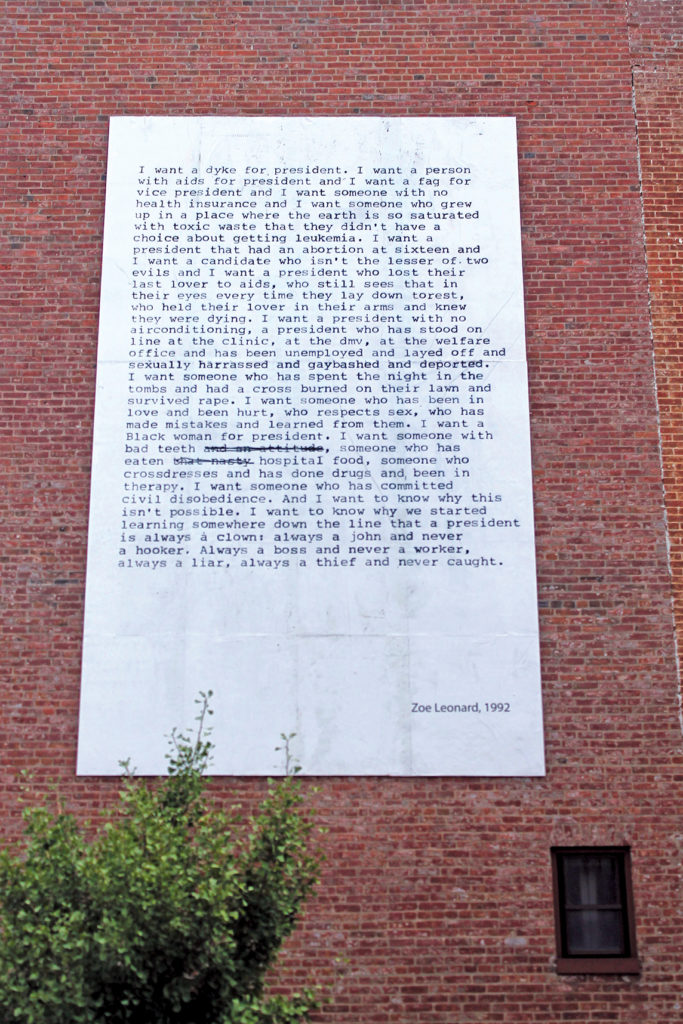

Fed up by their country’s bigoted failure, lesbian poet Eileen Myles announced a bid for president in the 1992 election against George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ross Perot. Myles came out in the race as “openly female,” drawing a pointed contrast between themself and their monochromatic opponents. Myles lost the race of course, but artist Zoe Leonard’s brash poem about their brash candidacy persists. “I Want a President” spits in the face of resignation, of accepting the way things have always been done — as well as the people doing them. It forces us to question what a leader really looks like, undermining traditional qualifications and prevailing notions of respectability.

I teach “I Want a President” toward the end of my semester-long writing elective, in the middle of a short unit I call “Another World Is Possible.” The unit invites students to dream of a better society by having them emulate a series of rebellious mentor texts, such as Leonard’s poem and Safia Elhillo’s “Self-Portrait with No Flag.” (For another example, see “A Field Trip to the Future,” Rethinking Schools, Fall 2020.) The unit serves as the fulcrum on which the course pivots: It comes after months of writing and sharing stories about our lives, but before we carry out our own local organizing campaign.

Although “I Want a President” focuses mostly on the identities of our politicians rather than the policies they support, it nevertheless dares students to overhaul their standards of electability, challenging them to reimagine who deserves to be handed power and why. To remember that democracy is — or should be — what we make of it.

* * *

As students pass copies of “I Want a President” around the circle, I start by addressing its language politics. I want to prepare everyone for two slurs we’re about to encounter: “dyke” and “fag.” As a queer teacher myself, I feel comfortable with this material and with reading aloud the poem. For other teachers, particularly my straight colleagues, I recommend playing a recording of the poem, an example of which I refer to below.

“Who remembers the word we learned for when a marginalized group takes back a word historically used as a slur against them?”

“Reclaim,” Emma answers, “like when I say I’m a ‘bad bitch.’”

“Exactly,” I say. “That’s what’s happening here in this poem. Its queer author, Zoe Leonard, uses words like ‘dyke’ and ‘fag’ to reclaim power — to flex her pride. As I read this poem, I want you to think about why she chooses to do that. Also underline the sentences you like best.”

“I want a dyke for president,” I read. “I want a person with AIDS for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.”

I pause and ask for explanations of AIDS and leukemia. Then I continue: “I want a president that had an abortion at 16 and I want a candidate who isn’t the lesser of two evils and I want a president who lost their last lover to AIDS, who still sees that in their eyes every time they lay down to rest, who held their lover in their arms and knew they were dying.”

When I finish the poem, I first have students echo some of their favorite lines. Then I ask, “When do you think Leonard wrote this?”

“There’s a lot of stuff about AIDS,” Nic says, “so back then?”

“Then when?” I ask.

“Like the ’60s?” Emma tries.

“Later . . .” I correct. I wait for a guesstimate but see no volunteers. “The ’80s and ’90s. Leonard wrote this for the 1992 presidential election, right at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Why do you think that is?”

“Didn’t the government not care?” Lisbeth says.

“Because it was like a lot of gay people who were dying,” Kiara adds. “That’s messed up.”

“So she was mad at the government?” Tyler asks.

“And that’s why she reclaims the slurs used against gay people,” Emma says.

“Yes!” I say. “So what was she trying to say?”

“She wants people to pick a different crayon,” Trista says. “She’s sick of these presidents, who all look the same, doing such a bad job.”

“She wants someone who’s been through stuff, like who knows how hard life is.”

“Right, a person who’s president to help people and not be a thief.”

“Perfect,” I say, starting to hand out highlighters. “We’re going to hear the poem again, and this time trans rapper Mykki Blanco, who’s HIV-positive, will perform it. As you listen, highlight the turning point, the line when things suddenly change in the poem.”

After watching Blanco’s stylized performance on YouTube, I ask for someone to share the turning point they marked. Nic suggests, “And I want to know why this isn’t possible.”

“Nice,” I say. “Would you mind reading that whole ending, after she finishes listing the kind of person she wants for president?”

“And I want to know why this isn’t possible,” Nic repeats. “I want to know why we started learning somewhere down the line that a president is always a clown. Always a john and never a hooker. Always a boss and never a worker. Always a liar, always a thief, and never caught.”

Lisbeth: “I feel like she’s accusing us of being brainwashed.”

“Brainwashed how?”

“Like we think that only a certain kind of person should be president. A ‘boss,’ a white guy in a suit or something, even though he’s probably just a ‘liar’ and a ‘thief.’”

“Even though what we really need,” Nic adds, “is a ‘worker’ — someone more like us.”

“Excellent!” I say. “So, now we know who Zoe Leonard wants for president — as Nic said, ‘someone more like us,’ the people who have been stuck on the margins of power, not the people in the center of it. And we hear how frustrated Leonard is that people, for some reason, seem to think it would be impossible. We’re ‘brainwashed,’ to use Lisbeth’s word, into thinking only one kind of person is electable as a leader. Now it’s your turn. Who do you all want for president?”

* * *

“You know the drill: It’s time to write our own poems.” I encourage students to stick close to Leonard’s poem as a mentor text, though depending on the context and the community that’s been built, it may be important to discourage the use of slurs. “Instead of ‘dyke’ in the first sentence,” I say, “what do you want to start off with?” I refer everyone back to the list on the board: “Think about all the identities not listed here. Who has historically — and wrongly — not been considered presidential?”

The poem dares students to overhaul their standards of electability, to reimagine who deserves to be handed power and why.

I field a handful of student ideas (“Latina,” “Muslim,” and “hippie”) in order to jump-start everyone’s thinking, then turn to craft. “What do you notice about how the poem is written?” I ask. “Let’s come up with a few characteristics.”

“There’s a lot of repetition.”

“Sometimes there are long sentences with ‘and’ after ‘and,’” Emma points out.

“And really short ones, too.”

“I love how she alternates between them and the rhythm that creates,” I say. “How would you describe her choice of words?”

“Really easy to read.”

“Great, and why do you think Leonard made some of these choices?”

“It’s like she wrote the poem to be like the person she wants for president. It’s not fancy. It’s just honest.”

“I love that, Trista,” I say, capturing these observations on the board in a second list. “Feel free to copy Leonard’s choices as a writer in your own poems, OK?”

I set the timer for 15 minutes. Students take to the poem without much trouble. It’s an accessible format, and they have all kinds of ideas, at least at first. To make sure they don’t lose steam, I chime in with questions to prompt them as they write: “What does your president look like? Or wear?” Then, a minute later: “What obstacles have they overcome?” I draft an example sentence on the board: “I want a softie for president, someone more concerned with kindness than ambition, bravery, or even intelligence.”

I float around the room and help students brainstorm ideas, usually pulled from their own lives. I notice that Nic looks stumped.

“You look up to your dad, right?” I ask him.

“Yeah, but I wouldn’t want him to be president.”

“Fair, but I wonder what qualities he has that you would want? I remember your beautiful piece about watching sunrise with him. That tells me he’s patient, which is something I’d want in my president — know what I mean?”

“I feel you,” he says.

With about five minutes left, I pause the timer and ask everyone to put their pens down. “Don’t forget about your turning point,” I say. “You can steal the line ‘And I want to know why this isn’t possible’ or you can come up with your own; either way, think about how you’re going to shift things in order to conclude the poem.”

When the timer goes off, I ask everyone in the circle to share at least one or two lines, a process that renders its own composite portrait:

“I want a president who lost a loved one to police brutality and I want a Native American candidate and I want a president who was held in concentration camps.”

“I want to know why wealthy + white = president.”

“I want a single mom for president.”

“I want a foster kid for president.”

“Always the straights and never the queers,” Kiara says.

“I want a president with no college fund, a president who’s worked over 40 hours a week only to end up barely surviving.”

“I want a president whose campaign slogan is ‘bare feet not arms,’ and a president who is more concerned with poverty and hunger than petty drug crimes.”

“I want to know why people are afraid of change,” Trista says, “because 44 out of 45 presidents have looked exactly the same and the same isn’t working.”

“Always a white man whose mommy and daddy are filthy rich and never his maid with multiple kids and multiple jobs and can barely afford rent. Always a snake with venom ready to pounce and never the antidote.”

“Team,” I say, “you all nailed it! Thank you.”

Finally, I invite a few volunteers to deliver their entire poems. Emma reads hers just before the bell rings:

I want a [baddie] for president. I want a person with dreadlocks for president and I want a Latina for vice president and I want someone with anxiety and depression and I want someone who grew up in a place so-called the hood where the earth is saturated in racist bullshit. I want a candidate who doesn’t look like a Hot Cheeto. I want a vovó as my president, a vovó who makes Portuguese soup and malasadas for the homeless. I want a president who drag races on the weekends. I want an old lady that lives alone with 15 cats for president. I want someone who has been to prison as my president because we all learn from our mistakes. And I want to know why this isn’t possible. I want to know why we started learning somewhere down the line that a president is always a millionaire. . . . Always talking and never taking action.

* * *

I have not yet taught “I Want a President” in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has killed more than half a million Americans. I anticipate that its historical resonance with the AIDS crisis — particularly the way both U.S. presidents failed to keep their people safe — will generate even deeper student engagement.

When I teach the poem again, I’d like to extend its identity politics at the same time that I trouble them. First, we need more diversity where else besides the White House? The Black Lives Matter at School demand to hire more Black teachers comes to mind. Next, I’d like to introduce the idea that I first learned from Kwame Ture and Charles V. Hamilton: Black representation does not equal Black power. In other words, a marginalized identity does not necessarily guarantee radical politics. I want to better tease out the connections between someone’s personal experiences and the public policies they might support.

Toward the end of the “Another World Is Possible” unit, students pick two of their mentor text imitations to revise in the computer lab. Leonard’s clear and fiery “I Want a President” is consistently the most popular option.

That could be because we still have such a long way to go. After all, the 2020 presidential race, fully three decades after Myles’ electoral stunt, pitted Donald Trump against Joe Biden: two old straight white men worth millions, with records either unconscionable or uninspiring — yet another political calculus that felt, to me at least, like choosing what Leonard calls “the lesser of two evils.”

Or it could be because “I Want a President” encourages students to exalt the people they know, their friends and family, ordinary Americans, themselves. It pushes them to conceive of themselves, no matter their identity or struggles, as possible leaders — as powerful and deserving of power.

Leonard demands that we reach for more crayons and reclaim our discolored democracy. That we the people — all of us worthy, all of us qualified — shake up the White House and every seat of power.