Unmasking Patriarchy

Analyzing texts to identify oppression with high school students

Aidia, a 9th grader, sat in the front of the class as she led an analysis of the poem “Unhide-able” from The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo. She asked, “Do you have any evidence that connects to the cycle of oppression?”

Guilia responded, “When the other girls call her a ‘ho,’ that is internalized oppression. . . . The girls have been oppressed and then they internalized that and projected it onto other women.”

“So you think that when she hears that she starts to believe it?” Aridia asked.

Guilia replied, “Yes, the other girls probably got called that too.”

Michael added, “Her being ‘thick’ builds the stereotype that she’s a ‘ho’ and people make assumptions about who she is. This leads to discrimination or oppression because they say bad things to her that make her want to use her fists, and it’s all a cycle.”

Our 9th- and 10th-grade students in this co-taught introductory gender studies course at Harvest Collegiate High School in New York City were not strangers to patriarchy and oppression. In fact, the course came about after a group of young women distraught by their experiences with sexual harassment at school sought counsel from Fayette Colón and Jessica Jean-Marie, two teacher confidants. After discussions and listening to students’ stories, the students requested a course be added to the curriculum on the importance of feminism. Fayette and Jessica took this request to the principal, Kate Burch, and Engendering Gender was born. Several years later, we, Frankee Grove, a special education teacher, and Fayette, a social studies teacher, worked together to grow this course.

Our students came from all five boroughs and a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds with 67 percent of students categorized as “economically disadvantaged” and 29 percent students with disabilities.

Students could take an advanced course on feminism in the 11th and 12th grade so we focused our Engendering Gender curriculum on topics we thought were foundational to understanding feminism. We wanted students to understand how patriarchy functions and how it connects to the feminist movement as well as homophobia and transphobia through these overarching questions:

• How do individual attitudes, institutions, and social norms/cultural traditions allow patriarchy to function within our society?

• To what extent do gender stereotypes allow or prevent us from being our true selves?

• How does patriarchy contribute to homophobia and transphobia?

Our goal was to provide students the tools to unmask oppression in their own lives, within popular culture, and within texts.

Developing Working Definitions

As Faye often told students, to dismantle oppressive systems we need to name the oppression. Historically oppressors limit knowledge so the people they oppress cannot identify let alone discuss their oppression.

Throughout the course we engaged in activities to allow students to develop working definitions of core vocabulary. We called them “working definitions” because we wanted students to know that these terms could be edited and redefined as we continued to learn more.

Given that patriarchy is a form of oppression, we thought it was important for students to understand the cyclical nature of oppression. Oppression is complex and manifests itself differently in different societies and at different points in history. The oppression of enslavement is not the oppression of the U.S. invasion of Vietnam, which is not the oppression of South African apartheid.

To understand gender oppression, we first had students think about their own connections and create definitions for key terms: oppression, stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and internalized oppression. We divided students into pairs and gave them one of the five words and chart paper. Students wrote their assigned word in the center. Then they responded to questions: What do these words mean to you? How are you connected to these words? What is your experience with these words? What are examples that can help us understand these words? What questions do you have?

After completing their own, students rotated to a new chart paper to engage with each word. Most students could describe their experiences with stereotypes. Although not the case with every Latinx student, several young Latinx women described the prevalence of machismo — the stereotype that men should be more dominant than women — in their household. As we expected, many students had a harder time vocalizing their connection with oppression and internalized oppression. Even though we knew this was possible, it was helpful to see what students already thought they knew about these words without the pressure of deconstructing text.

The next day, each pair returned to their original assigned vocabulary word. We gave students a definition using a variety of scholarly sources and then asked them to create their own definition. We encouraged students to provide an example for each word using comments from the previous class discussion. Then we came together as a class to develop definitions. In one class, students defined oppression as:

Harm being done to one group by another group. One group is privileged while the other doesn’t receive the same beneficial opportunities. Oppression reduces the potential for oppressed groups to be fully human. Within oppression a certain group benefits from social power and disadvantaged groups are seen as less human. In addition, oppression has to do with the institutions (laws/government, schools) that are put in place that allow oppression to exist.

We compiled the definitions that students received the following day. Then, with students in mixed groups, we gave them a circle with a space for each of the five words and asked them to think about how the words were connected in a cycle — how these ideas help oppression persist.

“Where do you see oppression beginning? How does it flow?” we asked.

Some students argued the cycle began with stereotypes because these inform the prejudices people have about particular social groups. Then discrimination, oppression, and internalized oppression occur. Students acknowledged that internalized oppression is connected to stereotypes and cements the cycle because people then perpetuate stereotypes about their groups. One student said, “Internalized oppression happens when women blame themselves or blame the victim for sexual harassment.”

Faye made her own iteration of a cycle of oppression and shared it with the class.

“I am reading a book, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Dr. Ibram Kendi. His writing reinforced the notion that oppression is not just ideas, but begins with people having a stake in exploiting others and needing an ideology to justify the exploitation. For this reason, I would place oppression at the beginning of the cycle.”

We also asked students to think about how the cycle of oppression connects to patriarchy. We believe these lessons defining terms were integral to students’ ability to have complex literary analysis discussions.

Analyzing Texts

Another key activity was weekly text analysis discussions. We wanted students to see how they could use a feminist lens to analyze the world. Each week we selected a current popular song, TV commercial, or young adult reading. Texts we analyzed include “If I Were a Boy” by Beyoncé, “The Best Men Can Be” 2019 Gillette commercial, “Mom, I’m Not a Girl”: Raising a Transgender Child Cosmopolitan YouTube, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk “We Should All Be Feminists,” and excerpts from Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur. Students often recommended texts.

Toward the beginning of the course, we read the poem “After” from The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, which had been recommended by a student (see Resource). Acevedo grew up in Harlem and attended a nearby high school in Manhattan. Many students were drawn to Acevedo’s work because they saw their lives in her poems.

Frankee began: “The reason we do these poems is to practice two habits, Habits of Evidence, selecting evidence and close reading, and Habit of Perspective, which is claims and reasons. You practice these habits when you annotate these poems, when you share in your turn-and-talk, and when you share with the class.”

To help students make connections to the course’s essential questions and build literary analysis skills, we photocopied prompts onto each text. The prompts included: “Circle three standout words and explain why you chose them. Why does each word stand out to you?” “Underline two feeling words and explain why you chose them. How does each word make you feel?” “Box one summary word and explain why you chose it. How does this word capture the essence of the poem for you?” “Make a connection to the parts of patriarchy, privilege, or gender stereotypes.”

After students received a copy of the poem, Frankee said, “Remember, the purpose of the first read is to listen and then on the second, make at least one annotation on every stanza and use the suggested prompts.” A student volunteered to read the poem aloud. Here is an excerpt:

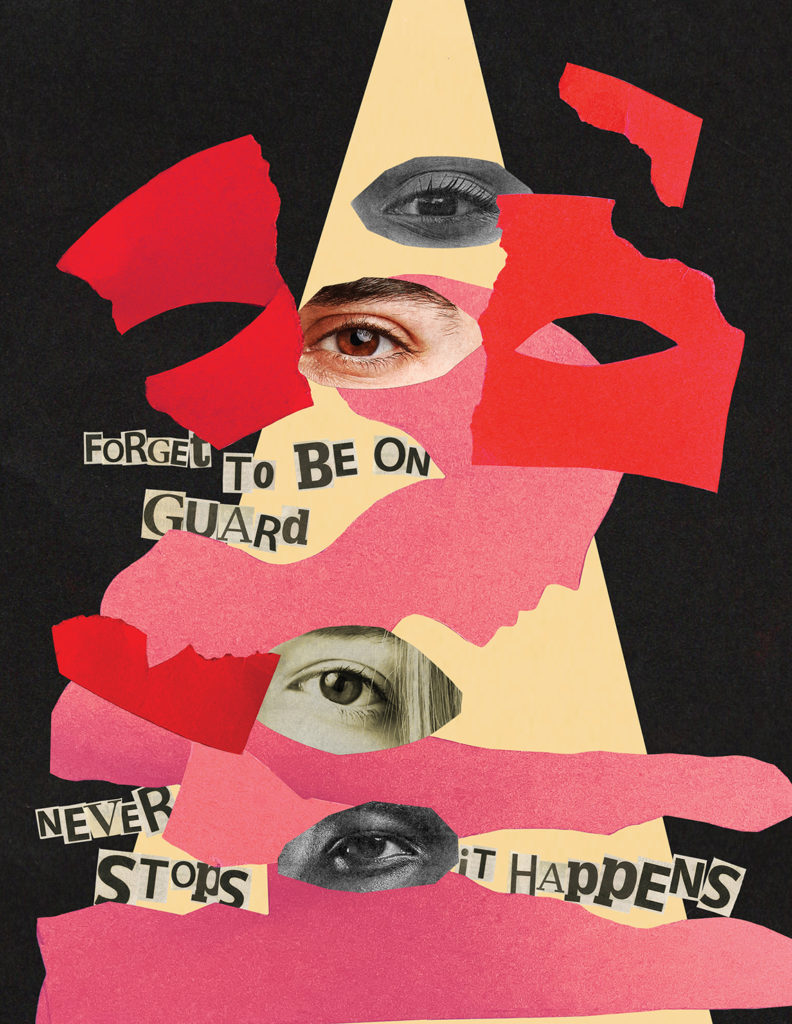

It happens when I’m at the bodegas.

It happens when I’m at school.

It happens when I’m on the train.

It happens when I’m standing

on the platform.

It happens when I’m sitting on the

stoop.

…

I should be used to it.

I shouldn’t get so angry

when boys — and sometimes

grown-ass men —

talk to me however they want

…

Frankee pointed to the question written on the whiteboard. “How does this text uphold or challenge gender stereotypes?” Students filled the poem’s margins with annotations as Frankee read the poem a second time.

After several minutes Frankee said, “Turn and talk to your table partner for two minutes about one thing you noticed in this poem.” We assigned seats in our class strategically so that table partners were composed of mixed-ability pairs. As students shared their thoughts, we each visited two or three pairs of students, and listened or prompted them to think more deeply: “Can you explain why you circled those words?”

Then Frankee brought the class back together: “As you read this poem, what did you notice?” Faye circulated the room and whispered to a student, “I loved your analysis of the repetition of ‘It happens when.’ Please share in the discussion.” Students began sharing cautiously; their thoughts gradually deepened as they built upon each other’s ideas.

For example, Zuri said: “I would like to add on to what Kenya said about the line ‘It happens when I forget to be on guard.’ I thought maybe that has to do with self-blame.”

“Great,” Frankee said. “Can you say more about that?”

“Like bad things can’t happen if she is more aware of herself,” responded Zuri.

“Can someone make a connection between that and the posters you made on the cycle of oppression?” Frankee asked, as she recorded students’ ideas on the poem projected with the document camera. “How does it connect to stereotypes, oppression, prejudice, discrimination, or internalized oppression?”

“This is like internalized oppression,” Elizabeth responded.

“Can you say more about how?” Frankee asked. “Because internalized is like she is oppressing herself.”

“She is going against herself by saying it’s all her fault and that idea is reinforced with the repetition of ‘I’m’ and ‘I.’ It is like she is taking responsibility for the action and not the men,” Amaya said. “And not just there but also in the last paragraph.”

“Elizabeth pointed out internalized oppression and Amaya pointed out the repetition. So great! That’s the first literary device I’ve heard so far, repetition,” said Frankee. “Amaya, I like that you added the function of the repetition. She didn’t just say that ‘I’m’ repeats but also explained why repetition is significant.”

“When she says ‘I should be used to it’ she is making it sound like it is OK for men to harass her yet she is still surprised,” added Janet. “It is almost like it is a social norm for guys to be able to harass girls.”

To help students see the connection between their ideas and those of the class, Frankee said, “So we see social norms as one of the parts of patriarchy playing out here.”

The weekly text analysis allowed us to pre-teach annotation, literary analysis, and discussion skills required to have meaningful seminar discussions.

Seminar Discussions

Throughout this course we talked about how patriarchy impacts everyone, and about how it specifically impacts the LGBTQIA+ community. The course ended with a student-led seminar focusing on how patriarchy connects to homophobia. As a scaffold, Frankee and Faye led an in-class reading and analysis of “Every Shade of Red,” a short story by Elliot Wake from the anthology All Out: The No-Longer Secret Stories of Queer Teens Throughout the Ages edited by Saundra Mitchell. “Every Shade of Red” is written by a transgender author and is a version of the fairytale Robin Hood with all queer characters where Robin is transgender.

To prepare, students completed a four-page graphic organizer. First, they chose one of two possible seminar questions: How does patriarchy connect to homophobia? To what extent do gender stereotypes allow or prevent us from being our true selves? Then students summarized the story, answered their question, found evidence to support their response, and analyzed how the author’s use of literary devices helped answer their question. Lastly, students made connections to the overarching concepts — gender roles, gender stereotypes, patriarchy, intersectionality, the cycle of oppression — and chose a quote to discuss.

Surprisingly, in both sections we taught, students focused on the same two sentences. Two characters, Will and Tuck, talked about the benefits and disadvantages of lesbian and gay couples within society. Tuck says to Will: “Women who are lovers aren’t looked at with revulsion. . . . Women are seen as less than men. That’s why they’re permitted indulgences — they’re pretty pets.”

Faye asked students, “What words stand out to you?”

Kenneth responded, “What does ‘permitted indulgences’ denote?” Faye threw it back to the class.

“It denotes a guilty pleasure,” Liana responded.

“So what does the narrator mean when they say women are ‘permitted indulgences’?” asked Faye.

Jessica responded, “Well, the word permitted denotes to be allowed, so I think this is saying that women are allowed to be lesbians. It is subliminally saying that women are not viewed as negatively as gay men.”

“It’s like Will wishes he was a lesbian because they are not as oppressed as gay men,” Ben added.

“How does this connect with patriarchy?” Faye asked.

“This connects to ideas about patriarchy,” said Elizabeth, “because women are seen as inferior to men so they are allowed to be desired, or to satisfy a more superior human being. Because women are over-objectified as sexual objects, and are always seen as a sexual symbol it is accepted for them to be together, or to want to be together.”

Later, during the seminar, a fishbowl discussion, we asked students on the outside of the circle to record at least three student comments and their own response on a graphic organizer.

We assigned students inside the fishbowl other roles: discussion-pusher, evidence-checker, question-poser, and connection-maker. We gave each role corresponding scaffolds. For example, scaffolds for the connection-maker included: How does what (student name) said connect with patriarchy? Who can add onto (student’s name) point?

At the start of the seminar, Storm, in the center of the fishbowl circle, asked, “How does patriarchy connect to homophobia? I’m not really getting that.”

“I think patriarchy contributes to homophobia because when society follows what powerful men say, when you come out as gay, you are going to be punished for it in some way,” Aisha responded. “In the story, when Will’s father punished his lover, it shows how men are just so powerful that they brainwash people into thinking that if you’re gay, you’re bad.”

“I think that some gay men have feminine traits and they think, well, this man has feminine traits and therefore he is less than a man because he acts like a woman,” Gina said.

Malik responded, “I agree with Gina that in this version of society women are treated as less than men. It’s also connected to how Robin was seen as less than everybody else, men and women, because he was gay and transgender. When you have two things going against you, it makes it a lot harder to be who you are, even though you are trying to be who you are.”

Eventually students used their text analyses and seminar discussions to write literary analysis essays.

. . .

In one discussion, Malik talked about how his father’s expectations of how a man should act impacted his mental health. Malik felt pressured to fit into this gender box. He shared that suppressing his emotions made him angry and depressed during middle school. But through conversations with his mother, a therapist, and our class, he was beginning to heal from the harm these expectations created.

Simply talking about patriarchal ideas seemed to shift students’ thinking. One unplanned discussion was a heated student-driven debate on whether it has the same implications when a man or a woman uses the word “bitch” toward a woman. Students used examples from their own lives and course readings, made comparisons between other denigrating words, and wove power, privilege, race, and the cycle of oppression into the conversation. They changed each other’s minds on this word so casually tossed around in the hallways and on social media. On the last day of class, Brian, who entered class skeptical of the content, reflected in a fishbowl discussion that he decided he would no longer use “bitch” and explained his thinking.

In the final unit we asked students to create a product bringing awareness to a topic we discussed in class. Some students chose to write children’s books, others created poems, while others made Instagram accounts. In the future, we will ask students to consider ways we can — and may already — resist and abolish patriarchal oppression and envision a post-patriarchal future.

Not every teacher is comfortable with nor has the privilege to talk in class about feminism, gender, homophobia, and transgender experiences. But to not have these conversations denies the experiences of the people we teach. Having conversations about patriarchy and its impact on individuals is one step toward dismantling it. l

The authors thank Jessica Jean-Marie, Sheila Kosoff, and Scott Storm for their integral role in the development of this course.

Resource

Acevedo, Elizabeth. 2018. The Poet X. HarperCollins.