Transforming Teacher Unions in a Post-Janus World

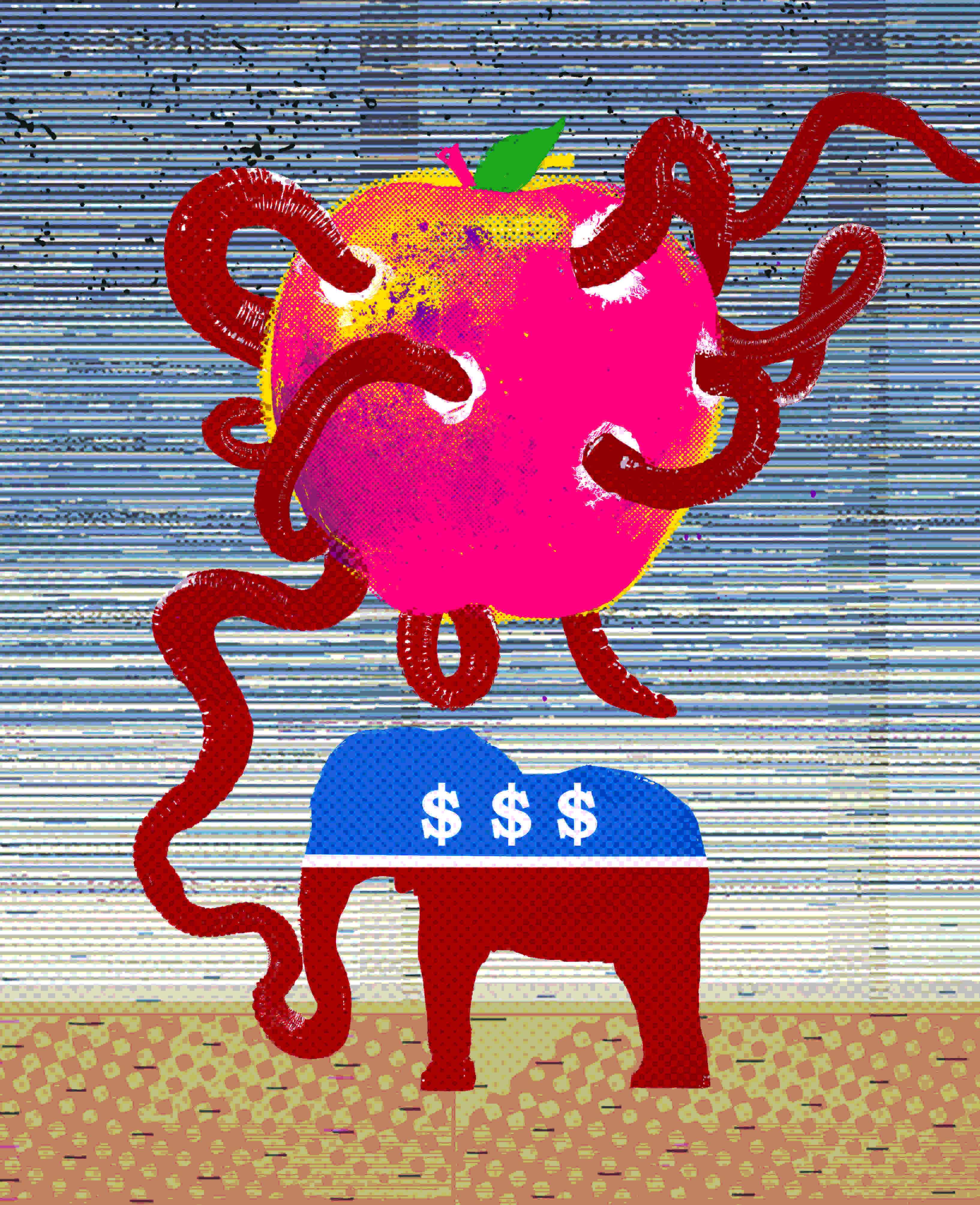

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

“I’m from Wisconsin, I’m from your future!” I start off my speech. Despite my love of science fiction, I’m not talking to sci-fi fans. I’m talking to teacher and other public sector activists at a conference in New York City on the future of labor and public institutions.

“My future, your future,” I continue, “started when Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker dropped the bomb in 2011 with an unprecedented attack on teachers, their unions, and the public’s schools.” A few months earlier, Walker had been elected governor during the 2010 Republican sweep of statehouses across the nation, the same year the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision enabled the 1 percent to tighten their stranglehold on many state and federal elected offices.

Fast-forward to 2018 and the future has arrived in the name of Janus v. AFSCME, a case that the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule on by midyear that could severely cripple public sector unions across the country.

Walker’s attack and the Janus litigation are similar not only because they directly attack working people and their right to organize, but because both have been bankrolled and directed by a network of billionaires, right-wing foundations, think tanks, and organizations that intend to destroy unions and inflict grave damage on public institutions.

However, these plutocratic assaults have inspired determined resistance during the past few years, sparking a new model of teacher unionism and an unprecedented rise in rank-and-file militancy exemplified by teacher strikes in Chicago, Seattle, and West Virginia. The subsequent flurry of walkouts and strikes in Kentucky, Oklahoma, Colorado, Arizona, and North Carolina are further evidence that educators are learning to fight back.

Despite this resistance, the victory of the plaintiffs in the Janus case would gravely damage public unions by abolishing “agency fees,” through which non-union members are required to pay their “fair share” to cover the costs of non-political activities of unions such as the securing of improved wages, benefits, and working conditions for all members.

In the 22 states that currently allow collection of agency fees, reduced union income would mean slashed budgets and cuts in unions’ capacities to protect members and support progressive social policies and candidates. For example, in Wisconsin — where the loss of agency fees were part of a broader assault on unions — the percentage of unionized public employees dropped from 46.6 percent in 2010 to 18.9 percent in 2017. Hundreds of union staff were let go, union offices sold, and some locals disappeared completely.

At the recent Labor Notes conference in Chicago of 3,000 rank-and-file union activists, I heard people in current so-called “right-to-work” states where agency fees are illegal say, “Janus won’t affect us because we’ve never had agency fees.”

But it will hit states like West Virginia that never had agency fees and also states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, and Iowa that lost agency fees after 2010, because national unions like AFSCME, AFT, NEA, and SEIU have historically used funds collected in agency fee states to organize and conduct political campaigns in states without non-agency fees. Moreover, with half of all union members in public sector jobs, this will substantively weaken the entire labor movement.

Janus v. AFSCME

Mark Janus, the plaintiff in the case, is a child support specialist for the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. AFSCME represents Janus and the other 35,000 state employees in Illinois. Janus doesn’t have to join the union, but he does have to pay his fair share (“agency fees”) to cover the costs of non-political activities of the union, like collective bargaining, from which he benefits.

The Liberty Justice Center and National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation, which represent Janus, claim that this is an infringement of his free speech and want to overturn the landmark 1977 U.S. Supreme Court Abood v. Detroit Board of Education decision, which ruled that teachers in the Detroit public schools don’t have to pay the political part of union dues, but do have to pay the “fair share” portion, a common practice in many private sector unions.

The Janus case is similar to a previous case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association that was argued in front of the Court two years ago. Due to the death of Antonin Scalia, the Court became deadlocked in a 4-4 split and the lower court decision affirming the constitutionality of agency fees was left in place — much to the relief of union members and leaders. But now most union leaders and followers of the Court anticipate a negative ruling on Janus.

Yet the potential damage of the likely decision in Janus can be countered through the upsurge of progressive activism engendered by the victory of Donald Trump. Barbara Madeloni, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association (MTA), conceded that the expected decision would mean that the MTA would “initially lose members.” But she is heartened by the rising tide of progressive consciousness. “People have more knowledge about the nature of the attacks on public education, the public good, and unions,” she noted. “There is a growing sense of the necessity for collective action — West Virginia and the Parkland students are two recent examples. That gives me hope that we have an opportunity to stem the losses and grow power.”

The Forces Behind the Janus Decision

The Janus legal assault on public workers has been championed by a powerful network of right-wing billionaires and foundations. They have augmented the Janus case and other legal challenges against public sector unions by funding candidates, organizations, and think tanks that promote two other major goals of the right wing: to privatize public education and other public programs like Social Security and to roll back the gains of the Civil Rights Movement, especially voting rights.

In the March 2018 edition of In These Times, Mary Bottari details the web of groups and “the $45 million money trail” behind Janus. She cautions that the extensive media coverage that has focused on the personal stories of Mark Janus and Rebecca Friedrichs “obscures the bigger picture” — the interconnected roles of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the State Policy Network (SPN), and the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity (AFP).

ALEC is a nonprofit organization that includes hundreds of state and federal legislators, corporations, and conservative think tanks and legal action groups. Started in 1973, it produces templates of pro-market, anti-democratic legislation whose goals include restricting union rights, ending environmental regulations, and privatizing public services. ALEC has especially focused on voter suppression targeting voters of color. In 2011-2012, for example, legislators in 41 states introduced more than 180 bills to restrict voting rights, many of them patterned after ALEC templates.

The State Policy Network knits together more than 60 conservative think tanks as members and dozens of affiliated organizations in all 50 states. According to the Center for Media and Democracy (CMD), “SPN groups operate as the policy, communications, and litigation arm of ALEC, giving the cookie-cutter ALEC agenda a sheen of academic legitimacy and state-based support.” CMD reported that in 2011 alone the combined income of all SPN groups was more than $83 million.

Americans for Prosperity, started in 2004 by David H. Koch and Charles Koch, with offices in more than 30 states, is a nonprofit organization that bankrolls a host of conservative policy initiatives, and has had an enormous impact. They heavily influence both state and national elections and policy decisions on a range of topics. For example, the Koch brothers’ AFP donated $8 million to defeat the 2012 campaign to recall Gov. Walker.

For decades, right-wing business leaders and foundations have built up this conservative network, spending many millions more than their liberal counterparts. An anti-labor Janus decision would worsen this disparity by crippling the capacity of the union movement to aid progressive organizations. For example, after Act 10 was passed in Wisconsin, the left-leaning think tank Institute for Wisconsin’s Future had to shut down because declining union membership led to diminished contributions from unions.

As tax-exempt nonprofits, ALEC, SPN, and AFP are not legally required to disclose their funders. But researchers have verified that these three organizations are sustained through donations by the Koch brothers, the Waltons, the Bradley Foundation, Facebook, Microsoft, Philip Morris, AT&T, Time Warner Cable, and many others.

Act 10 and the Wisconsin Uprising

Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and the Republicans who promoted Act 10 were financed by many of the above-mentioned groups, as well as Betsy DeVos’s American Federation for Children, and others. For more than two decades, such groups have poured money into political campaigns, think tanks, and legal groups to enlarge the Milwaukee school voucher program and expand it statewide. Currently the voucher programs in Wisconsin include more than 250 religious schools at an annual cost to taxpayers of nearly a quarter of a billion dollars, money that could be spent on resource-deprived public schools.

In 2011, when Wisconsin legislators turned their sights on destroying the main defenders of public schools, teacher and other public sector unions, they were unraveling a proud tradition of pro-labor policy within the state. Wisconsin had become the first state to legalize collective bargaining for public sector workers in 1959. In the following decades, even through hard financial times, millions in Wisconsin relied on unions for decent wages, retirement benefits, and healthcare.

Despite the unprecedented teacher strikes and walkouts, the many massive demonstrations of tens of thousands of people, and the 16-day occupation of the Capitol building, the governor and the Republican-controlled Legislature pushed through the worst constellation of labor laws in the nation.

Many commentators have written about the connections between Act 10 and the pending Janus decision, but it’s also important to note that while both prohibit agency fees, the Wisconsin Legislation contains several other draconian features, some of which have been adopted in Iowa and elsewhere, and will likely be widely promoted by conservative forces in state legislatures in a post-Janus world. The additional components of Act 10 included:

- Ending collective bargaining for most public sector unions. “Bargaining” can only include base wage increases not to exceed the cost of living thus capping real wage gains at zero percent.

- Giving local or state authorities the power to impose their “last best offer” at any time for any reason — which in my experience while union president in Milwaukee was often a zero percent pay increase.

- Prohibiting interest-based arbitration.

- Prohibiting arbitration of grievances.

- Ending payroll deduction.

- Requiring an annual “recertification” vote of 51 percent (not 50 percent plus 1) of eligible members voting yes (anyone not voting counts as a “no” vote).

- Mandatory increases in employee payment for pensions and health insurance — this meant an 8 percent or more cut in pay for most teachers.

In other words, Act 10 was a Janus decision on steroids. Recognizing the depths to which state legislatures will stoop to pass anti-labor legislation is important, given that Janus litigation is but one battle, albeit important, in the right wing’s class war to destroy public education and teacher unions.

Within two years, lawmakers in more than a dozen states passed laws that imitated various provisions of Act 10, including Iowa, Michigan, Indiana, and Tennessee. The Ohio Legislature eliminated collective bargaining and payroll dues deduction, only to have this action repealed in a highly contested statewide referendum.

And the Republican Wisconsin legislators were not quite done. Following Act 10 they made the largest cuts to public education since the Great Depression, gave tax breaks to the wealthy, passed voter suppression laws, restricted women’s right to choose, eliminated many environmental regulations, gerrymandered legislative districts, and restricted local control whenever a locality passed a law that ran counter to the Republican agenda. Despite the divisive and false promise by Walker during the Wisconsin Uprising — that he was only interested in restricting the rights of public sector workers — he signed a right-to-work (aka right-to-freeload) law that prohibits agency fees in the private sector four years later.

In the post-Act 10 and post-Janus world many of the political struggles will be at the state level. But they won’t just be legislative battles.

The Right’s Post-Janus Plans

For a sneak preview of the Right’s potential non-legislative strategies after the Janus decision, one can look at what happened after the lesser-known 2014 U.S. Supreme Court decision Harris v. Quinn. There the court ruled that home healthcare workers — virtually all of whom were paid by the state — were “quasi-public employees” and not covered under the provisions of the Abood decision. The unions representing these mainly female and non-white workers in Illinois and elsewhere took a hard hit, losing significant percentages of their members.

What’s most revealing, however, is how that decision empowered the right-wing Freedom Foundation, based in Olympia, Washington, to go after two SEIU Locals (775 and 925) that represent home care and childcare workers in Washington and Oregon.

The foundation ran aggressive campaigns that included full-color mailers, TV advertisements, YouTube videos, social media, emails, phone calls, and door-to-door canvassing of more than 10,000 households to encourage union members to opt out. The impact has been significant drops in union membership.

In a recent fundraising letter, Tom McCabe, CEO of the Freedom Foundation, wrote about the Janus decision: “We are gearing up in a major way to launch an extensive education and activation campaign to take full advantage of a favorable ruling in this historic case.” Noting that “unions won’t give up without a fight,” he adds that “they won’t go away until we drive the proverbial stake through their hearts and finish them off for good.” Among the foundation’s largest financial supporters are the Milwaukee-based Bradley Foundation and the Koch brothers-funded SPN.

The Freedom Foundation’s campaign in the Northwest has been promoted as a model within the SPN for what other member groups should do throughout the country to capitalize on the Janus decision. The SPN has boasted of an $8 million campaign they will launch after the Janus decision to “defund and defang” public sector unions. In an SPN fundraising letter obtained by the CMD, SPN President and CEO Tracie Sharp states:

I am writing you today to share with you our bold plans to permanently break the power of unions this year. . . . I am talking about the kind of dramatic reforms we’ve seen in recent years in Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan, and now West Virginia — freeing teachers and other government workers from coercive unionism — and spreading them across the nation. . . . I’m talking about permanently depriving the Left from access to millions of dollars in dues extracted from unwilling union members every election cycle.

Unions’ Post-Janus Plans

Although ALEC/SPN/AFP bankrolled legislators who passed anti-labor legislation in Wisconsin and West Virginia, they’ve not succeeded in dampening teacher activism and organizing in either place. Quite the opposite.

In West Virginia, some 20,000 teachers and educational support staff demonstrated that even without collective bargaining rights, agency fees, or payroll deductions, concerted collective action can be powerful and successful. Even more noteworthy, rank-and-file union members and non-members alike were the main people who led much of the organizing over Facebook, at local mass meetings, and at the state Capitol. Eventually the three main unions representing school workers played a supportive role, and the groundswell of activism has the potential of revitalizing and transforming teacher unionism in both states.

Nor will it be the same for the teachers in Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona, North Carolina, or in others states who have been inspired by the successful nine-day wildcat strike by West Virginia educators and support personnel. Rebecca Garelli, a leader of the grassroots group Arizona Educators United was able to get 24,000 educators to sign on to their #RedforEd campaign in a three-week campaign. When asked why she and others decided to start organizing, she replied, “West Virginia.”

Ironically, the grievous damage of the likely Janus decision may well have the unintended consequence of fostering intensified labor militancy. According to The New York Times, at the February 2018 Janus case hearing in the U.S. Supreme Court:

The solicitor general of Illinois — indirectly a party to the Janus case — warned in Monday’s oral arguments “that when unions are deprived of agency fees, they tend to become more militant, more confrontational.” And AFSCME’s counsel warned about the thousands of contracts that would have to be renegotiated in a climate where an agency fee is no longer a trade for a no-strike pledge, raising “an untold specter of labor unrest throughout the country.”

In Wisconsin, both agency fees and collective bargaining shaped union life for decades until Act 10 forced a titanic shift. One result was a large decline in union members. But at the same time the law seeded an increase in labor militancy and a move in some locals to transform some central tenets of teacher unionism.

For example, after Act 10 the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association (MTEA) and other union locals started to reimagine their unions. Like their peers in other states, many Wisconsin teachers had gotten used to a model of narrow “business unionism.” Though this model offered job protections and benefits, it meant that locals were staff-dominated and focused almost exclusively on contract negotiations and enforcement (mainly on bread-and-butter issues). Teachers were limited to a passive role and given a muted voice in critical decisions. Local leaders and activists, myself included, worked to transform our union to adopt the alternative of “social justice unionism.” This model stands on three legs: bread and butter, teaching and learning, and social justice. MTEA’s leaders embraced an organizing model that prioritized increasing union democracy and member engagement; building community coalitions for educational, racial, and social justice; building power at the school level; working with parents to reclaim our profession and our classrooms; and replacing collective bargaining with collective action.

Our MTEA members thronged to walk-ins, picket lines, rallies, and mass meetings. Collective action encompassed petitions, wearing union T-shirts on certain days and filling school board meetings with hundreds of members and supporters. We gained substantial victories. In coalition with community groups, the MTEA stopped a state takeover of “underachieving schools,” and halted further cuts in educator health benefits. We won more planning time for teachers, an end to outsourcing substitute teachers to private agencies, restoration of recess for elementary students, and the securing of a daily 45 minutes of uninterrupted playtime for 4- and 5-year-old kindergartens. Having hundreds of people winning victories, both large and small, demonstrates to people the power of collective action and a strong, democratic union.

We found in Wisconsin that despite the obvious financial drawbacks that accompanied an end to agency shop, the silver lining was not insignificant. The struggle against Act 10 politicized and radicalized a significant group of teachers and public sector workers around the state and even beyond state lines. Moreover, union leaders and members realized that to survive they needed to not only talk to every member to get them to join, but to demonstrate that the union is worth joining through collective actions. That gave added weight to those who sought to transform our union.

Jesse Sharkey, the vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union, told Rethinking Schools that he “never doubted that what happened in Wisconsin was very important in producing Occupy, and very important in producing the Chicago teacher strike in 2012.” He said that the West Virginia, Kentucky, and other wildcats and strikes were also inspiring and all connect to a similar condition, “the upwelling of class anger . . . [against the] right-wing politics in state legislatures and their treatment of state workers.”

When asked by Rethinking Schools how their unions were preparing for a negative Janus decision, union leaders from Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston, St. Paul, and the state of Massachusetts responded in similar ways. They described how their unions are systematically having small group and one-on-one discussions with all members, and listening to their concerns. Some are incorporating these one-on-ones into upcoming contract negotiations. Several are using the strategy of “bargaining for the common good,” whereby they involve parent and community members in their bargaining sessions with the school district to demand policies and programs that benefit all students and the broader community.

The campaigns go by different names. In Chicago it’s the “Re-Card and Resist Campaign.” In Los Angeles it’s the “All In” recommitment and re-card campaign. In Massachusetts it’s a 1-20-4 — one member leader, responsible for 20 members, and four contacts within the year to talk union issues and grow union power.

And in Boston it’s the “BTU All-In” with the acronym for building power of:

P professional growth and expertise

O organizing with our students, families, and schools

W worker rights and labor solidarity

E equity, inclusion, and social justice

R respect for our educators and our profession

All the leaders stressed it was not enough to talk to every member and to list the benefits of the union. It was also essential to listen to their concerns, and encourage their involvement in the union programs at their school or union level.

Jessica Tang, president of the Boston Teachers Union (BTU), said that when someone asks her, “How do I get involved in the union?” she responds with some questions: “What are you most passionate about? What issue do you care the most about? Or feel like you’d like to get more involved in?” If they say, for example, “Well, I am really concerned about special ed inclusion,” Tang replies, “Great we have an inclusion committee, I’ll add you to the list to get involved.”

Providing a broader vision of what the unions stand for and connecting the needs of individual members to broader community and economic issues were common themes. Nick Faber, president of the St. Paul Federation of Teachers, stressed that “Engaging members in a bold vision for public schools instead of a narrow vision of solely self-interest” and fighting for the “schools our children deserve.” He acknowledged that given the decline in union dues, “the Janus decision will force us to return to our roots in the labor movement and embrace the power of organizing.”

In 1904, the tireless defender of teachers and Chicago Teachers Federation pioneer Margaret Haley praised teachers as guardians of democracy, “whose special contribution to society is their own power to think, the moral courage to follow their convictions, and the training of citizens to think and to express thought in free and intelligent action.” In the current wave of teacher activism sweeping the country, we have validation of Haley’s noble hope and conviction. As Tang puts it, we are witnessing the rebirth of a struggle “about all workers, social justice, working conditions, and also what kind of society we want to live in.”

Bob Peterson (bob.e.peterson@gmail.com) taught 5th grade for 30 years. He is the former president of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association and is an editor of Rethinking Schools.