The Teacher Uprising of 2018

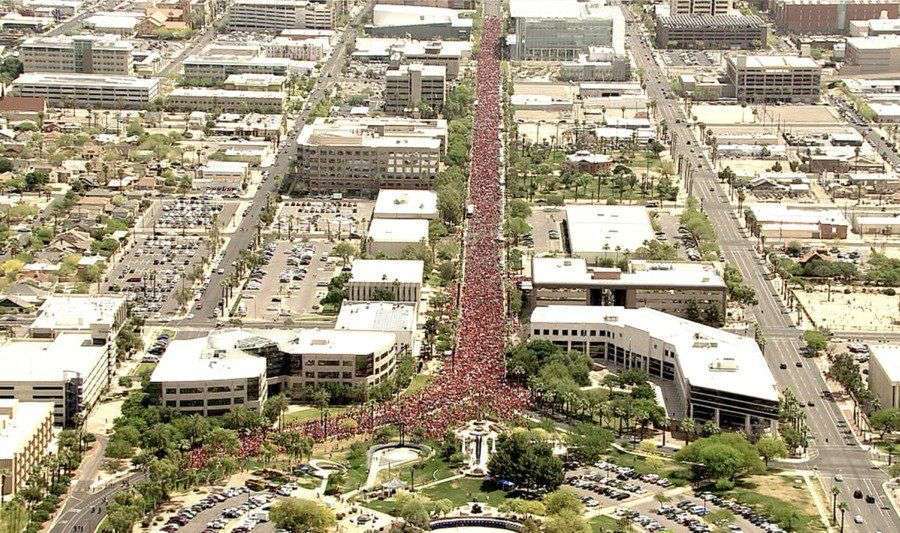

They’re calling it the “Education Spring,” and what started in a rural county in southwest West Virginia has spread like wildfire and inspired teachers and other public sector workers across the country.

“Healthcare was bad, the pay was bad, the working conditions were bad . . . you’ve got too many kids in the classroom. It’s the same issues that we see across the country and across the world and we saw that people were already really fed up and they wanted action,” West Virginia elementary school teacher and strike leader Olivia Morris explained to a packed crowd at the 2018 Labor Notes conference in early April in Chicago.

On top of those concerns, educators from Kentucky and Arizona list cuts to pensions, teacher shortages, poor and unsafe facilities, and lack of basic supplies and textbooks as additional reasons that led tens of thousands of teachers in several “red” states to launch wildcat strikes (strikes not officially sanctioned by union leadership).

In West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arizona, teachers and other education support personnel used Facebook and Twitter to do what their unions were unwilling or prohibited by law from doing: Pulling together tens of thousands of people — both union members and nonmembers — to stand up not only for educators, but also for the students in their under-resourced public education systems.

The militant history of miners in both West Virginia and Kentucky provided fertile soil for teacher wildcat strikes. Tammy Berlin, a teacher in Louisville, Kentucky, explained: “My grandpa was a steelworker and he participated in wildcat strikes throughout his career. My great-grandpa was . . . a field rep in the UMWA [United Mine Workers of America]. You just talk to people with any kind of union history and it’s just deeply ingrained that you do not cross the picket line.”

Rank-and-file teachers created both secret and public Facebook groups that grew rapidly to put together tens of thousands of teachers who shared their deep concerns about their working conditions and the problems facing their students. Teachers in these states are among the lowest paid in the nation, even though state legislatures provided coal, oil, and other industries massive tax cuts, simultaneously refusing wage increases for teachers and other public sector workers and forcing those workers to take real wage cuts by dramatically increasing the cost of health insurance.

Organizers shared tactics over social media: wearing red on “Fed Up Fridays,” having “Walk-Ins” in preparation for walkouts, building ties with parents and community members along with other unions, showing how to most effectively organize entire schools and districts, and providing evidence to both the rank-and-file leaders and hesitant union officials that it was the time to strike.

The educator unions in these states are weaker than in many others, unable to collectively bargain or collect “agency fees” — the subject of the pending Janus v. AFSCME litigation in front of the Supreme Court. Unencumbered by individual contracts at the local level and without strong union organization, the rank-and-file teachers self-organized and turned en masse toward their main enemy: the state legislatures, dominated by Koch brother and corporate-supported Republican legislators and governors.

The teachers at the Labor Notes conference made clear that they would “remember in November” and that their dislike of anti-public education politicians was nonpartisan. Emily Comer, a high school Spanish teacher from South Charleston, West Virginia, explained that “the Democrats in West Virginia had control of our state for 82 years and in that time they sold us to coal, and failed to give us collective bargaining.”

What was unique in some of these strikes was the support from the community. The support ranged from Teamsters and bus drivers supporting the strike, to churches and food pantries helping teachers prepare lunches for children who did not get school lunches during the strike, to principals and superintendents joining picket lines and marches and demanding that the state legislators agree to the teachers’ demands.

Such broad united fronts were essential for the success of the wildcat strikes — and it also gives a clear picture of what is possible when organizing reaches a broad audience.

The teacher leaders at the Labor Notes conference noted that union membership has increased as teachers have seen the help — albeit often tardy and tentative — provided by their unions. They also note that their Facebook groups aren’t going to last forever and are not only encouraging people to join unions, but also to continue organizing on their own to ensure that the Education Spring is rooted firmly in the rank and file at all schools and keeps going for many more seasons.

The question now is not whether teachers in other states will follow suit, but when and how they will use this momentum to win the quality of life they and their students deserve.

—Bob Peterson, Rethinking Schools editor

For information about Labor Notes and their work, go to www.labornotes.org.