The Struggle for Bilingual Education

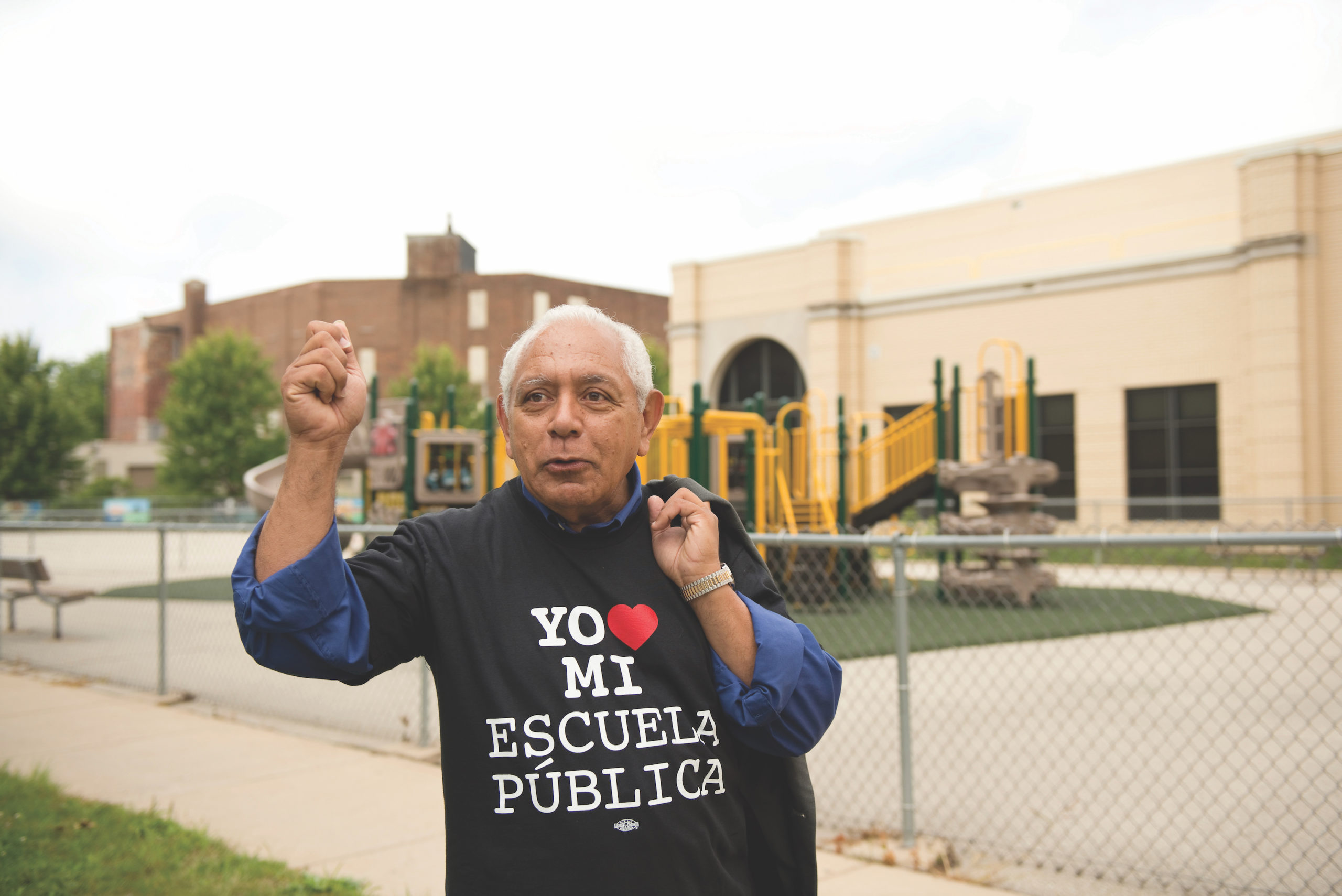

An Interview by Bob Peterson with Bilingual Education Advocate Tony Báez

Illustrator: Barbara Miner

Tony Báez is a longtime advocate for bilingual education. When he was a child, his parents moved regularly between New York City and Puerto Rico as migrant garment workers. After 6th grade, he remained in Puerto Rico until his early 20s when he moved to the United States and became involved in political movements in the Chicago and Milwaukee areas. Over several decades, Báez has worked as a community organizer, expert on bilingual education litigation, university instructor, and high school principal. He has also served as vice president of the Milwaukee Area Technical College, as executive director of Centro Hispano Milwaukee, and currently serves on the Milwaukee Board of School Directors. Bob Peterson (Contact Me) is a founding editor of Rethinking Schools and a founder of La Escuela Fratney in Milwaukee. He taught 5th grade for 30 years and served four years as president of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association. In the following interview, Báez talks about the history and current state of bilingual education, and describes how parents and educators successfully fought for a maintenance K-12 bilingual program in the Milwaukee Public Schools. This interview was adapted from a longer interview that appears in the new book by Rethinking Schools, Rethinking Bilingual Education.

Bob Peterson: How did bilingual education start in the United States?

Tony Báez: In modern times it started in the 1960s, as people in the Southwest of the United States and Cuban immigrants in Miami pushed for bilingual education to retain their home languages and improve the academic situation for their children. It emerged in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement. These were communities in battle, communities fighting for improvements in services. For example, in New York City, there was the community control movement. Evelina López Antonetty, a parent leader who was involved in improving schools, gradually began talking about bilingual education and about creating parent universities to prepare families to fight for bilingual education. Chicano leaders like Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales in Colorado connected Latino and Chicano cultures to the notion that bilingual/bicultural education is something we all deserve.

It wasn’t only people in the streets demanding bilingual education from school systems and elected officials. Litigation on language issues goes back to the 1940s. The push for bilingual education at the local level encouraged organizing at the national level as well. This led to Congress adding Title VII to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) when it was reauthorized in 1967. Title VII became known as the Bilingual Education Act of 1968 when President Johnson signed it in January of that year; it recognized multicultural education and bilingual education, and led to instructional programs that helped students whose home language was not English. But it was permissive, not mandatory. That meant that if you could get people together to write a proposal to the federal government and get a school district to submit it, you could draw on a little pot of money. Many of the communities fighting for bilingual education were not satisfied with the permissive nature of the legislation. People kept on organizing, and a lot of new litigation emerged between 1968 and 1974.

Peterson: How did that litigation affect the course of bilingual education?

Báez: The case United States v. State of Texas in San Felipe in 1970-1971 was groundbreaking. Judge William Wayne Justice ordered that two segregated districts be integrated. It’s an amazing case in which the judge mandated bilingual education and adequate bilingual staffing. He basically said that this country had to recognize the growth of the population that speaks a language other than English, and that it behooves us to learn their language.

However, the 1974 U.S. Supreme Court Lau v. Nichols decision, which dealt with Chinese students in San Francisco, brought that all down. Although it defended the civil right of national origin minority students to not be discriminated against because of their language, the suggested remedies were transitional — ESL classes or transitional bilingual education classes that moved children into all-English classes as soon as possible. This ruling became a precedent. The Lau lawyers didn’t insist on real bilingual education as a remedy, even though this was what parents and communities all over this country were asking for. By real, I mean “developmental” or what some call “maintenance” bilingual programs. The goal should be for children to maintain and develop their home language and build on their skills in their first language to learn English. In fact, research shows if students are strong in their home language, they will more rapidly learn a second language.

In another way, Lau was not really a good decision for us because it put the brakes on movements that combined community organizing and litigation. It was also near the end of the Civil Rights Movement and people were getting tired. This included lawyers, particularly those arguing for cases in court; they’d go to communities and say, “Look, after Lau you can’t win. You have to accept on precedent.”

That’s what happened in New York City with one of the most important cases, Aspira v. the New York Board of Education. My colleague Ricardo Fernandez and I had discussions with the lawyers and told them it was crazy to accept a transitional bilingual program. Sure, it was better than monolingual classrooms, but the lawyers represented 250,000 kids and should have demanded more. They said they had to accept the transitional program because the Supreme Court had spoken [Lau v. Nichols]. That deflated community efforts to organize for more robust bilingual programs.

After the 1974 Lau decision, the struggle for bilingual education was reduced to promoting transitional programs in most places. Latino communities had been driving the struggle for bilingual education up until then. After Lau, school districts were usually the ones making the decisions. Cities like Chicago that were in the midst of discussions or litigation accepted transitional bilingual education as a remedy.

Peterson: In that climate, how were the Latino community and its allies in Milwaukee able to win a maintenance (developmental) bilingual program?

Báez: People organized. In the late 1960s, Latino parents whose kids were “graduating” from a Spanish-language Head Start Center on Milwaukee’s near south side were concerned about where their children would go to school. They worked with teacher Olga Schwartz — who, a few years later, became director of bilingual education in the district — and applied for a federal grant from the Bilingual Education Act; it was funded.

That started bilingual programs at Vieau Elementary, Kosciuszko Middle School, and South Division High School in 1969. But Olga also recognized that the grant would end. She went to the parents and said, “We have a problem here. What if we write for another grant and we don’t get it?” So we all got involved in committees and started organizing. Parents at Vieau School, under the leadership of Mercedes Rivas, organized the Citywide Bilingual Bicultural Advisory Committee.

The committee decided that the best way to secure the program was to get the school board to assume funding. The parents were against the compromise of a transitional program, and decided to fight for a developmental program with bilingual classes from kindergarten through high school.

Peterson: How did you organize?

Báez: The committee held a parent meeting and a community meeting, and then we went to the school board en masse in 1972. After a couple of years, we worked out an agreement with the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS). It wasn’t easy. This all happened about the same time as the Lau decision, so some administrators argued that the MPS program should be transitional. We went before the school board and made the case that they should embrace language instruction differently from how people were doing it all over the country, and support developmental programs. Privately, we told them, “We don’t want to sue you, and we won’t if you give us bilingual education that allows our children to maintain our language.”

I was involved in organizing students to support bilingual education at that time. Actually, most of the concerns of parents and students at the high school level were about excessive suspensions of Latino kids, to the point that we had to create alternative schools for the dropouts. We told the school officials, “You could change the high push-out rate if you develop the capacity to deliver good bilingual programs at the high school level — not only at the elementary level.” And they said, “We don’t have the resources.” So we helped students organize walkouts at South Division, Lincoln, and Riverside high schools.

An agreement was finalized in 1974 that called for increasing bilingual programs and implementing culturally relevant curriculum that respected the language and culture of students. It was intended to reduce the push-out factor in high schools. It wasn’t just about language, but about helping Latino students develop a positive identity for themselves.

Peterson: What about organizing on the state level?

Báez: We mobilized and got the first bilingual act passed in 1975 in Wisconsin. That act funded the maintenance programs, but subsequent amendments to the act created transitional programs, where students were expected to “exit” the program once they became “proficient” in English. This was a problem, but we were at least able to solve it in Milwaukee. Even though kids were officially “exited” from the program, they would continue in the maintenance bilingual program unless the parent said, “Take them out.” So the MPS bilingual program remained a maintenance one; that helped us down the line. Many of the people working in bilingual education today in Milwaukee — teachers, principals, and other administrators — went through the Milwaukee bilingual program. Because of that, they are bilingual.

Peterson: How did the struggle for bilingual education in Milwaukee relate to the struggle for ethnic studies?

Báez: In 1969, the same year the bilingual program started in MPS, there was a protest at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (UWM) over treatment of Latinos. In November 1970, Latino student leaders took over the chancellor’s office and refused to leave. They weren’t demanding bilingual education, but rather ethnic studies classes and a Latino student center. Some of the same people involved in that struggle also fought beside the parent activists in the community for bilingual programs. In 1970, the Spanish Speaking Outreach Institute at UWM was founded. One of the actions of that center was to increase the number of ESL classes at UWM (and simultaneously at Milwaukee Area Technical College), with the hopes of raising the enrollment of Latino students.

Peterson: Returning to the national scene, presently there is a rapid expansion of dual-language bilingual programs in which native English speakers and native Spanish speakers learn in the same classrooms. What do you think of those programs?

Báez: The dual-language programs are a “growing up” of what we had before. With the large increase in the Spanish-speaking populations in the United States and the growth of movements for immigrant rights, people have started once again to more forcefully argue for maintaining their native languages. In some communities where bilingual programs have, in the past, been politically untenable, dual-language programs are a way to make sure children have access to a developmental program. In other places, such programs draw support and interest from families of all races who don’t speak the language that is the focus of the program.

The schools go by a variety of names — dual language, two-way bilingual, dual immersion. Different names, but the same goal: biliteracy and bilingualism, not the swift transition of language learners into all-English classes. La Escuela Fratney in Milwaukee is a good example of such a school, even though at the same time we have long-standing developmental bilingual education programs here as well.

Many advocates of bilingual education go the route of dual-language programs because then we are not fighting white parents; we are uniting with them to get what we need. We are bringing white parents and people of privilege into the process to recognize and fight for bilingualism for everybody.

It brings other communities in as well — in some communities in Texas, for example, the Black and Latino parents work closely together because of the dual-language programs. In Miami, North Carolina, New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts, too. Parents from different ethnic backgrounds talk to each other; they participate together in committees and councils. Dual-language programs have the effect of getting people engaged in transforming public education together.

Peterson: Why is it important for a teacher who believes in social justice to promote bilingual education?

Báez: Teaching a language well requires that teachers build a certain level of multiculturalism, tolerance, and connection to the world, to another part of humanity. Paulo Freire argued that a key to education is to listen and learn from the learner — that means their language.

Peterson: What does the future hold for bilingual education? What are some of the challenges?

Báez: Bilingual education is on the rise. In 2000, the U.S. Department of Education estimated there were around 260 dual-language schools in the nation and called for an increase. Now some estimates put the number at more than 2,000, almost a tenfold increase. What we need for people in the United States to recognize is that learning a second language should be part of what constitutes quality education in this country. We need to keep increasing the number of dual-language schools.

We also need to promote the preservation of Indigenous languages — and one of the best ways to do that is through quality bilingual programs.

There are serious challenges, such as finding enough qualified and fully bilingual teachers. We also need to figure out appropriate forms of assessment for bilingual programs, and fight against the over-testing that is hurting all kids. And, in the United States, we need to teach children not only to speak more than one language, but also to do so with a certain humanity. A good school instills in kids the sense that we are not the policemen of the world and that it’s not good to exert the arrogance of power. Rather, we are joining with people around the world through learning their languages; as we do so, we can come together to deal with our planet’s serious problems.

Peterson: What impact does the election of Donald Trump have on the struggle for bilingual education?

Báez: The problem is that Donald Trump knows very little about learning, cares very little about learning, and has surrounded himself with people like Betsy DeVos who know as little as he does. They push cuts to public education and programs that are very important to public schools like Medicaid and the after-school learning centers, and there are other proposed cuts that will also affect restorative practices — all while increasing support to private schools.

This comes at a time when more and more people, including some conservatives who may have voted for Trump, are recognizing how learning two languages is good for all children. States like Texas, Utah, and North Carolina are passing legislation promoting dual-language schools. A growing body of research and the successes of bilingual schools show the value of bilingual education and how bilingualism is supported by the science of neurology, by their academic success, and financial reasons.

And yet Trump and his associates are slashing programs that promote bilingualism and many other aspects of education that our children need. These severe cuts will create more trauma and stress for our kids and go directly against the notion that children should be able to learn their home language and that all children should learn a second language.

We must not accept such cuts and this movement to the right. We have to resist Trump’s federal policies while simultaneously pushing state legislatures and school districts to embrace what’s best for kids — bilingual programs, the importance of children’s play in preschool and elementary grades, and much more. This necessitates activism and coalitions at the local level that’s more substantial than before Trump was elected. We must not be fearful or silent. Our children depend on us.