The Story of One Union’s Journey Toward Disability Justice

Expanding Our Beliefs and Demands for Inclusive Education

Illustrator: Micah Bazant

I grew up in the suburbs of Detroit. In the early 1990s, my family fought to have my brother Micah, who had been labeled with an intellectual disability with needs similar to those with Down syndrome, included in the general education classroom with supports.

My parents are college-educated, speak English, and raised my brother and me with middle-class economic stability. We are white. These privileges meant that my parents could choose where to send my brother to school; they could take time off work without fear of losing their jobs to attend the hundreds of meetings; they could understand the meetings in English (although they didn’t necessarily understand the special education jargon). They didn’t have to wait months for translation services. They “spoke” the language of school — knowing who to contact when there were challenges and then demanding, year after year, that the school do better.

My family also held the unwavering belief that school would not simply be about providing access to independent life skills, coin counting, and specialized discrete trials. Micah wouldn’t go to school to become less disabled. Micah would go to school so that he could reach his full potential. Learning and developing would be a lifelong process. Micah deserved to learn alongside his neighbors and friends with and without disabilities.

Although Micah was successfully included in his K–12 experience, it was often despite the local district. It was only years earlier that students like my brother had been completely denied access to their local public school. They were kept in institutions (or none at all) that believed in a medical model that prioritized compliance and low expectations over learning and community. With the passage of Public Law 94-142 in 1975, students with disabilities were finally guaranteed a free appropriate public education. Laws alone do not guarantee access, but they begin to open doors.

My brother, now 36 years old, is considered part of the “ADA Generation.” These are the young people who have come of age since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, which is the most comprehensive disability-focused civil rights and antidiscrimination legislation in our country’s history. The ADA passed because of the highly intersectional and radical decades-long organizing of disabled activists, and, at times, in partnership with parents and caregivers of disabled children who were fighting for their child to belong in their neighborhood and community.

The values that guided the passage of the ADA intersect with the inclusive education movement that demands people with disabilities not simply be allowed to go to a segregated school (based on disability), but that the structures and policies in our communities be accessible and barrier free.

The values that guided the passage of the ADA intersect with the inclusive education movement that demands people with disabilities not simply be allowed to go to a segregated school (based on disability), but that the structures and policies in our communities be accessible and barrier free.

Although the full impact of the ADA continues to be seen (and fought for), it led to broader implications for Micah during and after school. There are things he can’t do — he can’t read in the formal sense, write more than his name, count mixed change, or drive a car. Because of the deep belief that education was a lifelong process, his learning did not get delineated into skills. High expectations allowed for his passions to be nurtured and in turn an interdependent community of support was built. He now works as a teaching assistant at Syracuse University training future teachers.

Although there were incredible teachers and paraprofessionals along the way who nurtured my brother, developed strong family-school partnerships, and sought out resources to expand their professional expertise, my parents often felt like they were fighting simply for his right to grow in his neighborhood school so that he, like all children, could reach their potential. I wonder what our family’s journey would have been like if our local teacher’s union had said, “We believe in inclusion. We want it to work for all kids in our district. We will fight with you.”

Inadequate Inclusion

Overwhelming national research concludes that, when implemented with adequate supports for students and teachers, inclusive classrooms are academically beneficial for students with — and without — disabilities. Inclusive classrooms are generally defined as classrooms in which natural proportions of students with and without disabilities receive supports, accommodations, and modifications to make progress on both Individualized Education Plan (IEP) goals and grade-level standards within the general education setting. Ideally, inclusive classrooms use flexible staffing models where adults use varied co-teaching practices (including station teaching where children rotate among independent, teacher-led, and student-led experiences) and flexible spaces that include opportunities for students to receive 1:1, small group, and whole group instruction. In particular, inclusion ensures that students with disabilities are held to high standards and given access to more opportunities. Inclusive education is not about finding the perfect curriculum, but a deep belief that all children, especially children with disabilities, can achieve at high levels.

In 2013, I became an inclusion teacher in Boston Public Schools (BPS), the same year the district began more systematically increasing the number of inclusive classrooms. However, when I started teaching, BPS inclusive classrooms had one teacher with multiple licenses (e.g., special education and elementary licenses) and one paraprofessional for 20 students. These classrooms had a particular number of students (up to five) with significant support needs (e.g., a student with Down syndrome) in the same classroom with students without significant support needs (i.e., students without a special education plan, students with fewer special education support needs, a student defined as a language learner).

In this model, many classrooms designated as “inclusion classrooms” rely on incredibly inadequate supports. A single often triple-certified teacher (a teacher with their content, special education, and English learner licenses) is responsible for both special education and general education supports: designing lesson plans, modifying the curriculum, conducting the special education assessments, writing the reports, and ensuring all students receive the interventions and supports they need. A job that is often held by multiple, licensed educators is the responsibility of one adult, leaving many paraprofessionals, teachers, and support staff feeling inadequate and ill-prepared — and making learning and teaching incredibly challenging.

As a new inclusion teacher, I struggled with the structural conditions that significantly limited the effectiveness of inclusion. I worried that what families and educators were witnessing would negatively impact their beliefs about the possibility of inclusion. To me, inclusion is not about simply putting students in the same space but about how we answer these questions:

- Do students with disabilities and without disabilities have the support they need to grow academically and socially?

- Do adults have the supports they need to meet students’ needs?

- Is the inclusion classroom promoting high expectations and a belief in what is possible?

As I connected with educators across the district and heard stories about inclusion in their classrooms, I also began to question racial inequities. According to the National Council on Disability in 2018, students of color with disabilities are less likely to be in inclusive classrooms than white students. When the location of a school district is factored in, these statistics widen dramatically. These statistics were on loud display in Boston.

As a new inclusion teacher in BPS, I quickly became agitated at the injustices and racism at play among policies around inclusion. Then I learned about the Inclusion Committee, run by and for members in the Boston Teachers Union (BTU), and joined with enthusiasm. I thought back to my brother’s story and realized this was historic. Teachers, yes teachers, were fighting for inclusion that supports children growing into their full potential. This committee’s initial work helped me, as a young teacher, to realize that unions could be leaders in the fight for inclusive education.

BTU Inclusion Committee

Unions have a mixed history when it comes to racial and social justice, despite their deep commitment to defending the rights of the working class. For example, instead of uniting with the just demands for racial desegregation of schools in Boston, in the 1970s the union took a more narrow approach that put the value of a negotiated contract over the aspirations of the historically underserved communities of color.

In recent years, however, the BTU, along with other teacher unions in Los Angeles and Chicago, have moved from a mostly service-driven union, focusing on enhancing and protecting wages and benefits, to social justice unions, where fighting for the schools our students, families, and communities deserve is matched with the learning and teaching conditions our members deserve. Instead of demanding the closure of inclusion classrooms to protect union members working in these conditions, the BTU Inclusion Committee was formed in 2013 to fight for better inclusion. To the union this meant students with and without disabilities learning in the same classroom with the adult supports required to make inclusion effective — no longer relying simply on multi-license teachers to provide all the special education services.

When I joined the BTU Inclusion Committee in 2017, I connected with union members who had already been engaged in the committee’s work to discuss inclusive practices across the city. They had already created surveys to document the teaching and learning conditions across varied inclusive classrooms to try to understand what made the inclusion rollout challenging. They also had created pamphlets to help families navigate the system and learn how to advocate for special education services (e.g., speech, occupational therapy, specialized reading programs). It was clear inclusion wasn’t done right but it wasn’t clear what role the union would take in this besides addressing grievances that emerged in individual schools.

Inclusion Done Right

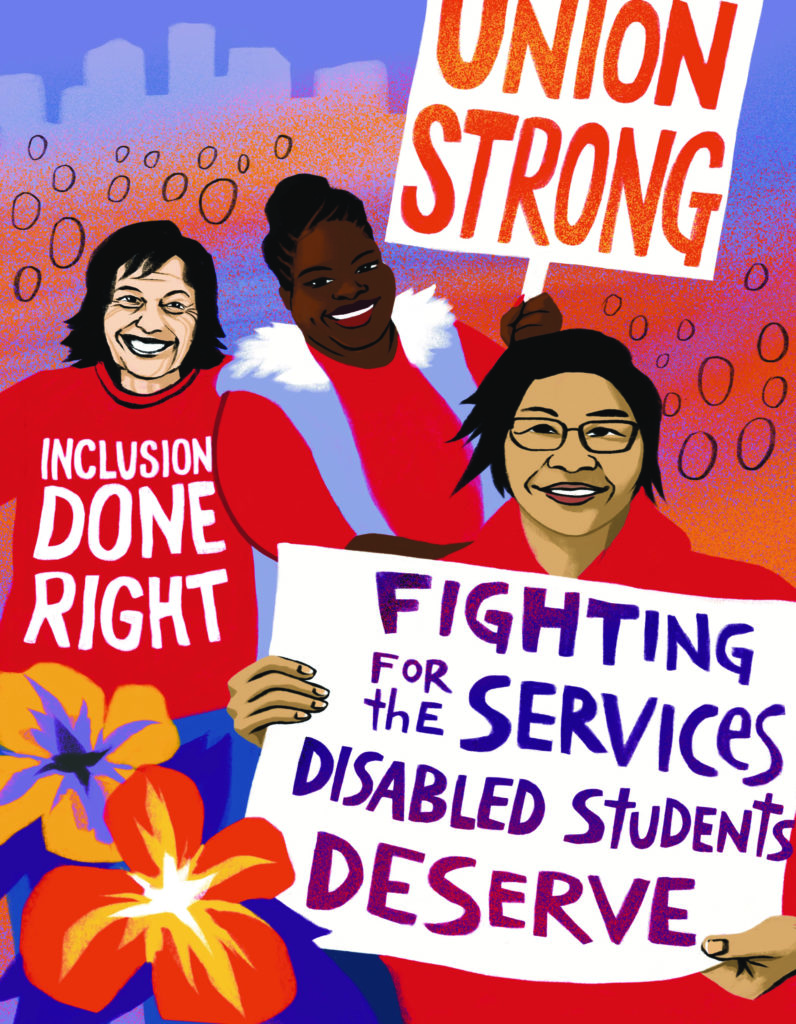

In 2018, with the advocacy, data collection, and work of the committee, the BTU made “inclusion done right” a central component of its upcoming contract negotiation with BPS. The union’s specific demand was to stop triple-certifying teachers as a cost-saving measure and instead put two teachers in each inclusion classroom to meet student needs.

BTU’s two-teacher demand was expensive. I didn’t know if we would win it. During contract negotiations, I marched with our union members carrying signs that said “Our students deserve . . . inclusion done right. Our students deserve . . . co-teaching.” Testimonies during school committee hearings were filled with the challenges of when inclusion was done wrong and beautiful stories about the possibilities created for kids when their needs were met with adequate teaching supports.

Often special education victories have been individual-family fights for the school/placement a family believes their child is entitled to by law. This was true in my brother’s story. Inclusion in Boston, our union was saying, would not be left up to who had resources and privilege; inclusion done right would be the expectation for all kids, especially students of color and others often excluded.

When the district and union settled the 2018–2021 contract in June 2019, it was clear there was no sweeping victory for inclusion. But there were some significant victories around inclusion that showed we were building momentum. For example, students who received English learner services must receive this support from a teacher other than their triple-certified classroom teacher. Students who had resource room minutes in their IEP (students who have disabilities but not significant support needs) must also have their minutes met from a teacher other than their classroom teacher. In addition, a more comprehensive inclusion working group was convened, bringing various stakeholders (parents, teachers, school leaders) together to discuss what inclusion should look like in our district.

Our BTU “Inclusion Done Right” committee and campaign also worked to build coalitions with more union members, families, and community organizers. We continued negotiation with the district and with national inclusion leaders. Instead of advocating only for co-teaching, our demands evolved. Inclusive education and schools that work for all are not about a one-size-fits-all model. Students require that we be creative, flexible, and responsive. We explored additional ways to fight for inclusive education beyond a two-teacher model.

Union President Jessica Tang pledged that we would carry on our fight for “inclusion done right.” When school began in the fall of 2019, the BTU launched a campaign that brought together scores of BTU members around the new demands: “More Educators NOT More Licenses” and “Fighting for the Services Our Students Deserve.”

Building Alliances

Part of coalition building was creating a common vision for inclusive schools. In fall 2019, participants at “Inclusion Awareness” events held at more than 20 schools across the district talked together about what was working in their inclusion classrooms, what was not working, and what it would take for educators to feel that they could meet the needs of all the students in their school.

At my elementary school, we brought together families and staff to discuss what kinds of classrooms we wanted. Overwhelmingly, families who did not have a child with a disability said, “I want my child to be around kids with disabilities.” This statement is radical. For so long, the narrative has been families do not want disabled students in their child’s classroom; the false fear that being with disabled kids lowers the rigor of the classroom. After the meeting, I called my parents and cried. I thought about how hard my parents had fought to have my brother feel valued in his school. Here I was with other parents who said they wanted disabled kids in their child’s classroom.

Overwhelmingly, families who did not have a child with a disability said, “I want my child to be around kids with disabilities.” This statement is radical. For so long, the narrative has been families do not want disabled students in their child’s classroom; the false fear that being with disabled kids lowers the rigor of the classroom.

Our “Inclusion Done Right” campaign also held strategic meetings throughout the fall and winter of 2019 and 2020, to continue discussing our campaign’s strategy and direction. I rushed into the first meeting late from school expecting to see our small but mighty group of 10 members in our union hall. Instead, I found empty pizza boxes, no empty seats, and more than 75 people. The mobilization was building.

We designed the strategic meetings to be accessible. The union provided interpretation services, childcare, and food. We were able to bring in families that represented the diversity of voices within our district. Just like at my school’s inclusion awareness event, there were also families who did not have a child with a disability and teachers who did not work directly with students with disabilities.

We also formed alliances, through meetings and many conversations, with members of the Boston Special Education Parent Advisory Council (SpedPac). SpedPac is a federally mandated support that every school district must support in organizing, and our alliance helped us put parents and students with disabilities at the center of this work. Roxi Harvey, parent leader of Boston SpedPac, recalled: “Our families need their voices to be heard and valued. Many of our families have experienced being devalued during school team meetings and their children have not experienced success . . . We have home data to share . . . It is important for everyone to know that when inclusion is done right, all children receive a challenging curriculum and studies show they have higher self-concepts.”

We listened to families’ stories. Then we listened to rehearsed testimonies to help people feel more confident sharing their stories publicly. Testimonies included parents from local justice groups and a parent from one of Boston’s predominantly Spanish-speaking neighborhoods who demanded, through a Spanish-English interpreter, that her daughter, who doesn’t have an IEP, receive a great education by ensuring that classrooms have adequate support to teach children with and without disabilities.

Cross-school teams also hosted their local city councilors for a meet-and-greet to discuss inclusion in our city.

To keep our demand loud during the 2019–2020 school year, we also made a commitment to be at meetings of the Boston School Committee, the mayor-appointed body that oversees the decisions made by BPS. For the first school committee meeting in 2020 we dressed in red, together more than 100 people strong. Families and teachers again shared powerful testimonies.

Inclusion and Black Lives Matter

Then the pandemic hit. Inclusion done right became a stronger rallying cry as we figured out how to support our students, families, and communities during a pandemic. We held our campaign meeting on Zoom in the first weeks during the school closure. More than 60 people attended — including families. We centered the immediate needs of families who were frustrated by the lack and inconsistency of special education services being delivered. Small breakout rooms paired union members with families. We listened.

At our last union membership meeting of the 2020 school year, a group of members quickly collaborated to construct a resolution in the wake of racial justice uprisings after the murder of George Floyd. Titled “Building an Anti-Racist Union” the resolution called for the removal of cops in our schools, the inclusion of ethnic studies curriculum, making the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action part of the job description of building reps, keeping a union Truth and Reconciliation Committee to address racism that has persisted in the union for generations and healing, and creating a statement about the Inclusion Done Right campaign. It stated:

THEREFORE, the Boston Teachers Union will continue its Inclusion Done Right campaign that has found that Boston Public School students of color are disproportionately placed in segregated settings and overrepresented in our special education system. Inclusion Done Right demands that students of color, particularly African American males, deserve high-quality inclusive schools that include multiple staff, rather than multiple-licensed teachers. All students, but especially those with disabilities, deserve teachers [who] are trained and experienced in de-escalation techniques to access curriculum in the least-restrictive setting possible.

With more than 400 members virtually signing on for the meeting, the resolution passed and now helps guide our anti-racist work, as a union and as educators in our schools. BTU member Natalia Cuadra-Saez said, “When BTU members voted to pass the Resolution for Building an Anti-Racist Union it felt like a historic moment. To me it’s part of a historic shift that is happening within the labor movement. More and more unions and rank-and-file members are embracing a social justice unionism model. We’re acknowledging as union members that our goal is not just to fight for economic justice, but also for racial justice and social justice as a whole. To include demands from the Inclusion Done Right campaign is part of that acknowledgement. Inclusion Done Right is a civil rights issue. Inclusion Done Right is a racial justice issue. And if we want to build an anti-racist union we know that we can’t just use buzzwords or wear a sticker. We need bold demands that tackle the systemic inequalities our members, students, and families deal with on a daily basis. Inclusion Done Right is one of those bold demands.”

BTU member Chantei Alves said, “When rank-and-file members came together to write the resolution, in the midst of multiple pandemics that were disproportionately affecting Black and Brown communities, I [as a Black BTU member] felt seen, heard, and valued by my colleagues and union leadership. As a Black inclusion teacher guiding Black and Brown students with learning challenges at the young ages of 4 and 5, including the Inclusion Done Right campaign was just as significant because equitable and high-quality instruction and services for our students and families, as well as consistent support for special education teachers, specifically addresses one of the most racist and segregated structures within the education system.”

At the final school committee hearing of the 2020 school year, Tang presented a report the union wrote documenting how racial justice work intersects with the Inclusion Done Right campaign, which calls out the inequities in our district: White students are two times less likely to be placed in segregated special education spaces (Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s District Review Report, released in March 2020). In the district’s solidarity statement of Black Lives Matter, we were highlighting how ensuring equitable inclusion is an essential part of Black Lives Matter in BPS.

Toward Disability Justice

Throughout the campaign, union members have had to identify their fears and intentionally support each other. Teachers named fears about administration’s retaliation around pushing back against district policies at IEP meetings. Paraprofessionals named fears about job security if they spoke up about poor working and teaching conditions in a classroom. Families named fears about the impact their activism might have on their own children’s educational journeys.

As we move forward, I hope we can center disabled people and disability justice in our work. Disability justice is designed around principles including intersectionality, leadership of those most impacted, commitment to cross-movement organizing, sustainability, interdependence (not independence), collective access, and collective liberation. Ultimately, disability justice in schools challenges us to move beyond “fitting in,” as happened with the initial rollout of inclusion in Boston, to recognizing how our communities and schools must be radically transformed. “Fitting in” means we just place disabled people in inherently ableist spaces. Inclusive education done right means that our schools evolve to meet the needs of all, especially those who have been most marginalized by the system.

As we move forward, I hope we can center disabled people and disability justice in our work. Disability justice is designed around principles including intersectionality, leadership of those most impacted, commitment to cross-movement organizing, sustainability, interdependence (not independence), collective access, and collective liberation.

We need a national network of union members who are committed to broadening their fight for inclusive schools. We have the opportunity to actively undo the racial and social inequities that our schools replicate. Across the nation, 83 percent of students with intellectual disabilities are left out of inclusive settings; among these, students of color with disabilities are disproportionately excluded. We must work to center the demands and stories of those with disabilities and families of color. Our campaign must continue to engage in these difficult conversations and help us all learn that inclusive schools must be for all kids, not just those with privileges. Ultimately, this is a transformative fight for all of us — union members, other adults working at schools, children, families, and our schools.

Resources

National Council on Disability. Feb. 7, 2018. IDEA Series: The Segregation of Students with Disabilities. ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Segregation-SWD_508.pdf.

Berne, Patty. June 9, 2015. “Disability Justice — a Working Draft by Patty Berne.” Sins Invalid. www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/disability-justice-a-working-draft-by-patty-berne.

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. “Boston Public Schools District Review Report 2020.”

Resolution for Building an Anti-Racist Union passed by the Boston Teachers Union on June 10, 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1GhrLqiiAjDACqJJeSoTONM9K0JO2nw5XWgHuthO9Gjs/edit.