The Story of a Seed

Food Sovereignty in an Elementary Classroom

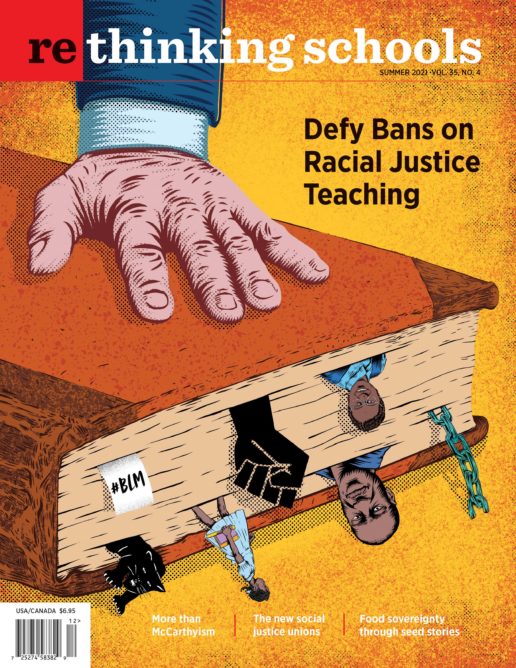

Illustrator: Ricardo Levins Morales

“Every seed has a story,” I say as I hold up a small potato for 20 sets of 1st-grade eyes.

I teach agriculture at a charter school in Oregon that roots classroom content in an agricultural framework. Throughout the year, students explore subjects like math, language arts, science, and history through hands-on agricultural observation and practice. Seed studies form the backbone of this agricultural programming.

Through the stories of seeds, I want my students to experience the cultural foundation of food sovereignty. The international community of peasant farmers, La Vía Campesina, defines food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.” Within this framework, I see an opportunity to empower my students as seed savers, protecting cultural heritage through healthy food.

Every seed has a story. To know the story of a seed enables an understanding of that seed’s origins and impacts. To understand a seed’s impact gives my students power: the power to choose what kind of a world they want to grow.

The impacts of the seeds that grow our food reverberate through cultural and environmental landscapes. There are seeds with stories of resilience that preserve cultural traditions and feed the communities that protect them. There are seeds whose stories have been lost to colonization and oppression. There are seeds that are forced upon farmers by global agribusiness, extinguishing biodiversity, establishing an addiction to synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, and destroying livelihoods. I want to empower my students with the choice between a seed that sustains people and ecosystems and a seed that destroys them.

“Food sovereignty” will not be part of their vocabulary until 5th grade. The foundation my students need to fully understand this term takes time to build in a capitalist society and educational system, where the dominant narrative does not value diverse cultural ways of knowing. The term food sovereignty has little meaning to a student who does not value their own cultural heritage, much less someone else’s. This perspective takes time and practice to cultivate. Through the stories of seeds and the celebration of their own food heritage, I aim to ingrain that shared value so that they can define food sovereignty for themselves.

Since kindergarten, we have played with all sorts of different seeds to create patterns, organizing them by shape, size, or color. Some of these seeds were saved from the garden or my days in farming, but most of them were freely given from seed companies. All it takes is an email to ask for last year’s unsold seed packets.

By their 1st-grade year, they have picked dried pea seeds from withering plants in the school garden and scooped slippery seeds out of squash cavities. This particular squash was the North Georgia Candy Roaster, a fruit the students learned was originally grown by Cherokee tribes in the southern Appalachians for more than 100 years. Every seed has a story.

Some of our pea and squash seeds made it back into the ground, planted for next year’s harvest. We donated the rest of the seeds to our school’s service-learning partner, Neighbors Nourishing Communities, a nonprofit that addresses local food insecurity by distributing gardening resources to those in need. Throughout the school, students design and decorate seed packets to fill with seeds they have saved from the garden. These seed packets are distributed to local gardeners at Neighbors Nourishing Communities’ annual plant and seed handout, in order to, as 2nd-grade student Tia puts it, “Spread the seed we need!” 2021 marks our sixth year of partnership with the organization. This seed sharing ritual has become a joyous annual activity for my students.

Classroom activities shift slightly from year to year with each type of seed. In February of their 1st-grade year, this class was moving on to examine the story of a particular seed that wouldn’t fit in a seed packet, the Makah Ozette potato.

Technically, a seed potato is not a potato seed. Truly a tuber, a seed potato is a specialized storage stem planted beneath the soil, which produces nodes or eyes all over its surface. These nodes grow up through the soil as shoots and stems, eventually producing fruits that hold true potato seeds, which can be saved. These small seeds, which look similar to tomato seeds, have more genetic variability than the tuber, and are often used to facilitate hybridization. The tuber, however, will produce an exact genetic copy of the parent plant, preserving the potato’s original taste, texture, and growing habits — the very features for which communities preserve particular seeds of different foods. For functional and cultural purposes, this group of 6- and 7-year-olds defines seed potatoes as seeds.

The Story of the Makah Ozette

To begin, I hold up a Makah Ozette tuber and say, “The Makah Ozette is a special potato with a special story.” Heads turn to observe this new seed specimen. “The Makah Tribe has grown these potatoes for more than 200 years in Neah Bay, Washington.” I move my potato-filled hand to the map that hangs over the whiteboard. I point to Neah Bay, 300 miles north of our school, located just south of Portland, Oregon.

I turn back to the potato. It is covered in a multitude of indented eyes, little sprouts that squint sporadically along its thin, smooth, brown skin, more than a typical grocery variety potato. As I pass out a Makah Ozette to each student, I ask them to close their eyes. “Use your sense of touch to tell your neighbor about your potato.”

I hear murmurs of “smooth,” “hard,” “bumpy,” “round,” and “long” start to circulate around the classroom. I ask them to open their eyes. “Now try using your sense of sight to tell your neighbor about your potato,” I say.

Students look skeptically at the tubers in their hands, leaning over to their desk mates to compare specimens. I watch them rub their thumbs over the potatoes’ curves, bumps, and indentations. I hear many of the same words they used to describe how the potatoes felt as well as “brown,” “wobbly,” “a little green,” “alive,” “cute,” and “small.”

Enzo finally calls out with conviction, “Ms. Blood, these are not potatoes.”

“What makes you say that?” I ask.

“The ones we have at my house are bigger. Their skin is darker brown and bumpy,” he describes, his hands showing us their size.

“The russet potato,” I nod in affirmation, “is a well-known potato.” I display a photo of a russet potato for Enzo to verify. I love that he speaks from his experience, and I want other students to do so as well. I want them to connect their own stories to the seed stories we learn in the classroom. Hands are high around the room when I ask if other students are familiar with the russet.

Then I ask, “Has anyone seen a potato at home that looks different from a russet?”

Stella tips out of her chair as she flies into her story of the small, red-skinned potatoes that she loves to eat when her mother cooks them with butter. Students’ hands go up around the room, eyes big, their heads nodding vigorously. “I can see there is a lot of potato knowledge in this room!” I exclaim. I ask them to share their “potato stories” with one another.

As I walk around the room listening, I hear stories of potato pancakes, potato soups, mashed potatoes, and french fries. Through these food stories, students share memories of smells, tastes, and connection with family and friends.

“My grandma makes us potato pancakes,” shares Tay.

“So does my dad!” responds Eduardo.

“What is a potato pancake?” asks Ellie, as she listens to Tay and Eduardo’s excited descriptions of their culinary experiences.

I put the Makah Ozette down and reach in a second bag to hold up a small, elongated, red potato that seems to fit Stella’s description. “Does this potato look similar to the potatoes at your house?” I ask her.

“Yeah!” Stella exclaims, then tilts her head and furrows her brow, “Sort of . . . yours is long. My mom’s are smaller and short.”

I start to pull out more potatoes from the bag. I ask students to show me with a thumbs up, down, or sideways to compare the potatoes they have seen before to the different colors, shapes, and sizes of potatoes from my bag.

I circle back to Enzo’s earlier assertion, “You all have proof that potatoes come in different shapes, colors, and sizes. Each potato looks a little different because they have different stories. Today we are going to learn the story of the Makah Ozette.”

We use the Makah Ozette potatoes in our hands to kinesthetically engage in the seed’s story together. Twenty-one Makah Ozette potatoes are wiggling high in the air as I illustrate this potato’s historical journey across the map. Holding the Makah Ozette near Peru, I begin, “Before this type of potato was named the Makah Ozette, the Spanish took its ancestors from Incan potato growers in South America.” My potato hand slowly moves north on the map. “The Spanish sailed with it up the West Coast to North America.”

I pause with my potato off the coast of Washington. “When they arrived in Neah Bay, they planted their potatoes. Before they were ready to harvest, the Spanish abandoned their potatoes and sailed away. The people who first lived in Neah Bay, the Makah Tribe, cared for the potatoes after the Spanish left them. The Makah weeded, watered, and harvested the potatoes. For the past 200 years, the Makah people have continued to grow these potatoes. That is why it is called the Makah Ozette potato. It was named after their ancient fishing village on Lake Ozette.” I point to Lake Ozette on the map.

“Every living thing has a different story,” I repeat. I want them to absorb this concept, because diversity is one of the central values of food sovereignty. In order for each community to “define its own food and agriculture systems,” the narrative that defines those systems needs to be storied by its members. Centuries of land appropriation, resource monopolization, and social injustice that have deprived BIPOC people of culturally appropriate foods disproportionately plagues their communities. Teaching students to recognize diversity in the stories of seeds is my way of teaching them to respect ways of knowing and eating other than their own, especially each other’s.

We spend the rest of the class examining the similarities and differences between each of their Makah Ozette spud specimens. Students compare amongst themselves, competing to see whose potato has the most eyes, which tuber is the biggest or smallest. Table groups line up their potatoes in order of size. We illustrate our botanical observations, drawing details like the mysterious eyes as accurately as we can.

Sustaining the Story

When we meet again, the Makah Ozette potatoes are waiting at their desks. We take a moment to reacquaint ourselves with the unique story of the Makah Ozette. Students take turns to tell their partners the story of the potato. I watch their potatoes dance through the air, following the same historical journey from Incan civilizations to the Makah Nation. I hear the echo of “200 years” around the classroom.

“Every living thing has a different story.”

I want this seed’s story to stick in their minds. It is different from the commercially grown russet potato they might find in a grocery store. This story offers a clear and visionary tale of food sovereignty and a lesson of resilience through struggle and oppression. Throughout decades of legislated dispossession and genocide, the Makah hold on to this vital element of their food heritage. The Makah Ozette remains a source of physical and cultural sustenance for the Makah Tribe, illustrating the power of culinary tradition in sustaining community food systems. It is a story that can be found in communities around the world. In fact, the Makah Tribe’s efforts to preserve the Makah Ozette have drawn people from across the United States to join in solidarity. By engaging students to join this movement in our classroom, I hope to inspire them to replicate it for other seeds with a similar story.

Back at the front of the classroom, I celebrate their remembrance of the Makah Ozette. “There is more to this story,” I tell them. “The Makah Tribe work very hard to keep this seed alive. It has not been easy! When the United States government came to Neah Bay 150 years ago, they took much of the land the Makah Tribe had lived on. They punished the Makah for speaking their language and practicing their own ways of life. But the Makah stayed strong. They have protected many of their traditions. One of the traditions they protected was growing and eating the Makah Ozette potato.”

Marta suddenly raises her hand. “How did you get these potatoes from the Makah?” This question hits me hard, because it is the greatest weakness of this lesson, and a microcosm of the social injustice we are studying. The discussion of Makah culture and its preservation is happening without Makah representation in my classroom. The extent of my engagement with the Makah Tribe has been a short dialogue with members from the Makah Cultural and Research Center in Neah Bay to coordinate a future visit to the school. I also take students on a virtual tour of the center, which includes the Makah Museum, to observe pictures of Makah basketry, carving, and canoes. Marta’s question reinforces my commitment to host the Makah in a way that supports their vision for education around the Makah Ozette.

I go on to answer Marta’s question: “Joann Reckling, a seed saver, grows acres and acres of the Makah Ozette potato at Tranquil Farm, just a few minutes away from our school. She works with other farmers, eaters, and seed savers across the United States to grow the Makah Ozette potato and to make sure that this seed’s story continues.” I show them the Slow Food Ark of Taste’s webpage dedicated to the Makah Ozette as proof of this coordinated effort. As part of the Ark of Taste, Joann focuses primarily on organic cultivation of the Makah Ozette potato. She provides Makah Ozette potato seed to gardeners and farmers across the Pacific Northwest who are interested in keeping this Indigenous food from disappearing. She had given us these potatoes on one condition, I tell the class seriously, “That we would continue the Makah Ozette potato’s story. That every year, we would plant, grow, harvest, and share them. She said we could eat some, but she made me promise that we would plant, grow, harvest, and share the rest. I promised her that we would be seed savers too.”

“What do you think might happen to a potato seed if it is not planted in the soil?” I ask. The pea and squash seeds we looked at previously did not show any visual signs of change when they were not planted, so I do not expect them to know the answer.

I hold up an old, moldy, shriveled up potato. “This potato seed was harvested by digging it out of the soil two years ago. When I harvested it, it looked like a fresh potato that we could eat. But we didn’t eat it, and we never planted it. Over time, it started to change. How does this potato look different from a fresh potato?” I hold up a fresh Makah Ozette potato next to its counterpart.

I hear a few answers pop around the room, “It’s wrinkly! Moldy! Squishy! Gross!”

Ariel says, “It looks dead.”

“You’re right!” I tell Ariel. “Seeds don’t last forever. If a seed is not planted in time, it will lose the life that it has inside and die. Some seeds will stay alive for two, three, or four years. Some seeds can last for thousands of years! But potatoes need to be planted every single year. What would happen to the Makah’s potatoes if they were not planted every year?” I ask.

“They would all die!” yells Theo.

“Exactly!” I say, excited. “The Makah Tribe saved their potato seeds each year by planting them. Today, people all over the United States know the seed’s story and are planting and saving this seed. The farmer who gave us this seed told me this story, and now I am telling you. Now you are a part of saving this important seed. After all of the Makah’s hard work, should we just let these Makah Ozette potato seeds and their story shrivel up and die?”

“No!” respond a few students, their eyes open wide and their heads shaking back and forth.

“We have to plant them in the garden!” exclaims Adriana.

Sharing the Story

As an agriculture teacher, I could choose to teach my students the dominant narrative of globalized commercial agriculture. Per the Green Revolution, we could use words like “technology” and “innovation” in ways that would reduce the intricately complex practice of growing food to a numbers game. We could ponder questions like “How to feed 10 billion people in the year 2050?” and “Which corn variety has the highest yield?” or “What are the five parts of the food pyramid?” without questioning the roots of hunger and diet-related disease that disproportionately affect BIPOC communities. We could celebrate temporary technical solutions that exacerbate social and ecological injustice like food aid, free trade, and synthetic seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. In fact, these are the conversations held by commercial agricultural institutions since the 1940s and ’50s. Today, this dialogue characterizes food systems around the world and dominates curriculum.

It is easy to get swept up in the temporary fixes that monocropping and genetic modification offer. I want to prepare my students to navigate this discourse with a critical mindset and an eye for justice, looking for signs of diversity, cultural resilience, and solutions to hunger that prioritize food sovereignty. I hope they remember “every seed has a story” when they go to the market or plant a seed in the soil.

The way potatoes grow in our climate, their harvest date is in July, when students are out of school. I organize our annual harvesting party, to pull potatoes and other crops like garlic, but most students aren’t in attendance. For that reason, I store these potatoes until they return in September as 2nd graders.

As I push a wheelbarrow of their harvested potatoes to the front of the classroom, I tell students, “The Makah have been generous to share their Makah Ozette potato seed with us. Now, how can we be generous with the Makah Ozette potatoes you have grown from their gift?”

“We can send them back to the Makah Tribe!” exclaims Elizabeth.

“We could write them thank you cards!” says Belen.

“That is an excellent idea!” I say. “Who else could we be generous with?” I ask.

“We could cook them for the whole school,” smiles Gabriel.

“I want to cook them for my family,” says Theodore.

“Can I bring some home to my mom?” asks Tali.

I write “Makah” “school,” “students,” and “family” up on the board. “Who else could we share these seeds with?” I ask.

I want them to see that the impact of their project extends beyond our school community. I want them to think about creating local solutions to food insecurity and sustaining the agricultural heritage of the Makah Tribe. I remind them of kindergarten and the peas and squash seed we saved to share through Neighbors Nourishing Communities’ annual plant and seed handout.

“But,” Mira interjects the blissful rollout of resources, “the growers have to make the same promise we did. They can’t let the seed’s story end! They have to be seed savers!”