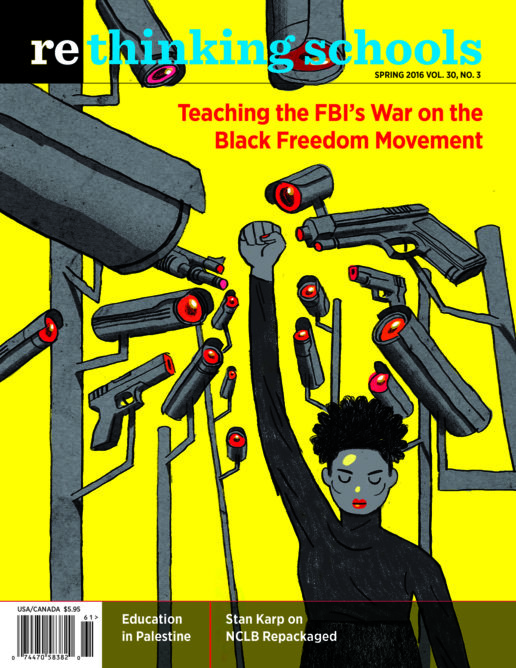

“The Most Gentrified City of the Century”

Illustrator: Chris Kindred

Boise-Eliot/Humboldt School is a special place. It stands, 90-year-old red brick and mortar, amongst newly constructed condos, craft breweries, and combination laundromat-bars, just a block off historic Mississippi Avenue in the Albina area of North Portland, Oregon. It is an obstinate place that, despite its decreasing enrollment and “level one” Oregon State School Report Card status, has survived two separate school closures and simply refused to yield to the forces of gentrification.

A recent article in Governing: The States and Localities described Portland as “the most gentrified city of the century,” and the vast majority of the gentrified tracts are in North and Northeast Portland. Although North Portland’s demographics have drastically changed over the last two decades, from predominantly African American to predominantly white, Boise-Eliot/Humboldt’s student population hasn’t. In a neighborhood that is mostly white, we serve the largest volume of African American students in the state. Less than half of the students who live within our district boundary attend our school, and less than half of our student population lives in our neighborhood.

As gentrification has forced out many working-class families of color, affluent white families, who often choose to opt out of the neighborhood’s “failing” public schools, have moved in. Many of the students we teach at Boise-Eliot/Humboldt travel long distances, riding public transportation from far in East Portland, to attend our historically Black school. Families often use the addresses of aunties, grandmas, and friends to ensure that their sons and daughters will continue a legacy that sometimes dates back to the flood of 1948, which destroyed the World War II shipyard-worker city of Vanport and pushed its largely African American population into the Albina area.

The mechanisms of segregated housing—unfair lending practices, exclusionary laws, eminent domain, urban renewal, and gentrification—are not distinct to Portland. These racist laws and practices continue to affect communities nationally. Our school, our neighborhood, and our students are part of a larger story, a larger conversation. Because this history is so relevant to our students’ lives and is often ignored by traditional curriculum, we decided to co-teach an integrated language arts/social studies unit on gentrification and neighborhood history to our 8th graders.

We hoped this unit would say: Yes, you’ve lived this. You are living this. Your experiences are important. And, in the face of a changing community, you have something to share that is irreplaceable. You have the opportunity to educate our community and neighborhood about a destructive process that we’ve all been part of.

We wanted to help students wade through Oregon’s often ignored racial history, and to help them feel empowered to go beyond the facts and into the messiness of evaluation and activism. What resulted was a yearlong process that included facilitating structured student discussions; interviewing families; lots of reading and writing; self-publishing a digital multimedia book about the history of race in our state, city, and neighborhood; and a student-driven community activism project.

“Those Fancy Apartments Are Going Up All Over”

We decided to launch our unit with a general overview of gentrification—What is it? How has our neighborhood changed?—and students’ personal narratives. We wanted to show students that this unit was deeply rooted in their own experiences. Moreover, we hoped to encourage students to find their own voices to talk back to discriminatory practices.

In his social studies class, Jeff began with a simple definition: “Gentrification is a change in a neighborhood,” he said, writing the sentence as a bullet point on a note sheet beneath the document camera. The students dutifully copied the sentence in the notes section of their social studies notebooks. “Our neighborhood has gone through gentrification. A lot of you grew up here. How have you seen it change?” Jeff asked the class.

The students looked up from their notes, and a few hands went halfway up. “The New Seasons [a high-end grocery store] is new. Does that count?” asked Jada.

“Absolutely, that’s a change. Let’s write it down.” Jeff wrote a second bullet in the notes: “How has our neighborhood changed?” and beneath it he put a dash and wrote “New Seasons Market.”

A few more hands shot up. “There are a lot more white people,” stated Jayla. “I’m not trying to be racist, but I was walking down Mississippi and I didn’t see any Black people at all, and it didn’t used to be like that.”

“They tore down that one bar; what was it called?” asked Aaliyah.

“LV’s 22? Wasn’t that it?” offered Jayla, leaning forward in her seat.

“That’s interesting. What are they building in its place?” Jeff prodded.

“Probably some of those fancy new apartments. They’re going up all over, down Mississippi and Vancouver and Williams,” said Jayla.

Jeff added “a lot of new buildings” to the list as students named more changes they had seen in the neighborhood. MyKyla talked about her family moving. Jordan said the butcher shop no longer carried certain items, like oxtails, that her grandma wanted. Hailey mentioned that Self-Enhancement, Inc. (a Black community-focused charter school and community resource) had moved its services out to East Portland—or, as our students call it, “The Numbers” (a reference to street names like 157th Avenue). Aaliyah talked about the new bike lanes on Vancouver and Williams, major thoroughfares a few blocks from the school. It just kept coming. After a substantial list was created, we organized our experiences into three categories: people, physical structures, and community services.

“But gentrification isn’t any old change,” Jeff said. “It impacts certain people more than others, doesn’t it? Jayla, what did you notice about race in our neighborhood? Can you connect that to gentrification?”

“Well,” Jayla began, “it seems like the people who were already here, Black people, have been hurt more.”

Later, we would discuss specific aspects of Portland’s development, like using eminent domain to force people of color and low-income families out of their homes. But the students seemed ready to write, and Jeff introduced the first assignment of our unit—the personal narrative: “We’ve all seen or experienced at least one aspect of gentrification, but many of our families have been here for generations.”

“My great-grandma went here!” shouted a student.

“Over the weekend you are going to interview your parents, grandma, auntie, someone you live with, about your family’s experiences with gentrification. You can ask them whatever you want, but there are a few questions that you have to ask. Turn your notebooks to your writing section and let’s get them written down. What section?”

“Writing!” came a chorus of voices.

Leaving half a page for each question, students wrote down the following:

Why do we live where we live?

Why do I attend Boise-Eliot/Humboldt?

How have the changes in our neighborhood affected our family?

Do you think these changes are good or bad?

What are your hopes for me, my education, and our school?”

Students seemed excited about the activity, and we hoped that this excitement would bring families and their stories into the curriculum. Almost immediately, we started hearing from family members and school staff about the impact the project was having on students. One parent commented, “This project is important because it’s about what is really going on in our kids’ lives.” Our students were talking about gentrification in the halls and other classes, on the bus ride home to East Portland, and around their kitchen tables.

When they returned to social studies class on Monday, many came with stories to share. “Did you know my great-grandpa owned the Desert Motel and the Rose City Cab Company? And those are the oldest African American businesses in the city?” Jada exclaimed when given the opportunity to share her research with the class.

Happy to build on the enthusiasm generated by students’ discussions with their families, Jeff introduced the narrative through a prompt: “As a member of this school community, you have experienced gentrification in some capacity. Use your family interviews to craft a personal narrative that explores your family’s experience.”

Over the next two weeks we used our school’s computers to draft, edit, and revise the narratives. As the students wrote, Jeff furiously read, responded, and asked questions. What emerged was a complex portrait of family history and a changing community.

For example, Cayden wrote: “On holidays like Thanksgiving, 4th of July, and birthdays, it is harder to get my whole family all in one house because my uncle and cousins live out in The Numbers.” She also tried to make sense of the relationship between the changing demographics of North Portland, where the school is, and East Portland, The Numbers, where her family now lives:

The only kind of people we see in East Portland are Hispanic and African American people. Finally, one day I asked my uncle, “Why don’t you ever see Caucasian people in this neighborhood?”

“A few years back if we would have lived out here you would have seen a lot of white people, but now you mostly see African American people because the prices of the houses in North and Northeast have raised, and I would not be able to afford the houses closer, near my job,” he replied.

Many students expressed a frustration that likely mirrored that of their family members. Hailey, our 8th-grade vice president, wrote:

I don’t think white folks get it. You are making things more expensive for us people, in a place where we still are struggling to survive. We don’t wanna be a part of it anymore because we know that it’s going to be too expensive, and what we want the neighborhood to be will not be considered.

“He Was Even a Doctor”

Students recognized and could describe the changes that were taking place in North Portland. They saw the unfairness of having to move due to rent hikes and the decline of Section 8 (subsidized) housing in the neighborhood. However, students were left wondering why and how this had happened. What were the explicit and intentional policies whitewashing the neighborhood? The purpose of the subsequent reading lessons was to help students understand the mechanisms and policies behind the changes. We wanted to give them specific people, places and policies so that they could analyze the marginalization many were experiencing and take on the role of activist.

When students entered language arts class on Monday, each table had a manila envelope with five copies of the same article. Becky explained: “Today we are going to build on what you’ve learned in Mr. Waters’ class by reading parts of a research project, The History of Portland’s African American Community, 1805 to the Present. We’re doing this for three reasons: to learn more about the history of our neighborhood, to practice reading tricky text by chunking and paraphrasing, and to see what good nonfiction writing looks like.” Becky instructed students to read through the article once independently and to underline what confused or surprised them.

As Becky circulated through the room, she began to notice patterns in what students were highlighting. After 10 minutes, she asked students to share out what they were wondering and uncovering.

Elijah raised his hand. “Did you know that Dr. Unthank, the one from Unthank Park, had a dead cat thrown at his house because he moved into a white neighborhood down by Grant High School?”

“Yeah, and they broke his windows and threw garbage all over the place. And someone wanted to give him $1,500 if he would move out,” Jacob added.

“He was even a doctor, and they did that.”

As we continued reading, chunking, paraphrasing, and discussing, students kept a chart in their notebooks that was split into three categories: people, places, and policies. They continued to record names: DeNorval Unthank; the Dude Ranch, the center of the Portland jazz and arts scene in the 1940s; and the Hill Block Building, the center of Black-owned business in Northeast Portland.

New vocabulary surfaced. We took time to define and discuss important terms: Oregon Exclusion Laws (the legal exclusion of people of color from the state), redlining (the purposeful and legal confinement of people of color within specific neighborhoods), and eminent domain (the city’s ability to oust residents based on a justification that the property could be better used to serve the public) all created a climate that has encouraged the exploitation of the city’s citizens of color.

We wanted the students to see how the terms connected and interacted. We used the history of the Hill Block Building and Legacy Emanuel Hospital to illustrate this.

The iconic metal dome of the Hill Block Building, all that’s left of the historic building, now sits atop a gazebo in a neighborhood park a handful of blocks from the school, something the students were quick to point out.

“What do we know about why that building was torn down?” Becky asked. “And how Legacy Emanuel was developed?”

Hailey raised her hand, her eyes on the article on her desk. “This article says that 188 houses were torn down to expand the hospital.”

“Didn’t the hospital apologize for that?” came a voice from the back.

“How could they just tear down houses?” came a surprised and angry response.

“Well, they were ‘blighted,'” Hailey explained, looking through her graphic organizer, “and so the city said they could. But the article also says that the city was purposefully ignoring neighborhood requests for help, and we know that the city used”—she looked down at her paper again—”they used redlining to make sure that the neighborhood was mostly Black people in the first place. So basically, they forced people to live there, ignored them, and then forced them to move by using eminent domain.”

“And the Hill Block Building?” Becky asked, returning to the original question.

“That building was torn down, too,” Hailey stated flatly.

As our notebook charts filled with names and ideas, students began to connect the current changes with what they had learned.

Emiliano commented: “Places getting expensive here is like opposite redlining. It’s keeping people out of the neighborhood now.”

Students had begun to see the current changes in the neighborhood as the most recent iteration of a long history of purposeful disenfranchisement and systematic racism.

“What Can We Do About This?”

As the group settled into Jeff’s class, sharpening pencils and scraping chairs, he typed the starter question into a PowerPoint: “Why are we learning about this?”

“Well,” Hailey began, “we are learning about this because it’s important.”

“But why does it matter?” Cayden quipped.

The students looked at one another. “It matters because people have been hurt,” Hailey said, a little unsure of herself. “Most of my family has had to move out to The Numbers, and a lot of these people moving into the neighborhood, they don’t even know that.” Many students nodded.

“What can we do about this? Should we do anything?” Jeff asked.

“Should we tell them?” asked Malik, often one of the most soft-spoken boys in the room.

The students settled on an answer: Yes, we should tell them. We should tell the stories of urban renewal, of Legacy Emanuel Hospital, of a vibrant Black middle class. We should tell the stories of Vanport. We should tell them that exclusion laws, codified by Chief Justice Reuben P. Boise, our school’s namesake, required beatings for African Americans caught living in the state. The students wanted to tell it all.

After class, we reflected on Hailey’s candor and Malik’s question. This was an opportunity to make it about something bigger than the essay, or the test, or the assignments, or the grade. Percolating in Becky’s mind was an iBook project she had learned about a few months previously during a workshop with Peter Pappas, a faculty member at the University of Portland. With his graduate students, Pappas had edited an iBook about Portland’s Japantown in the 1950s. The iBook platform included widgets, scrolling sidebars, and wipe-away images to showcase student writing. More importantly, it was possible to make a compendium of class articles available to the broader community as a free download.

It seemed simple enough: Students would need to write and revise their pieces, Becky would compile the articles, and then together we would find a way to actually get people in the neighborhood to read it.

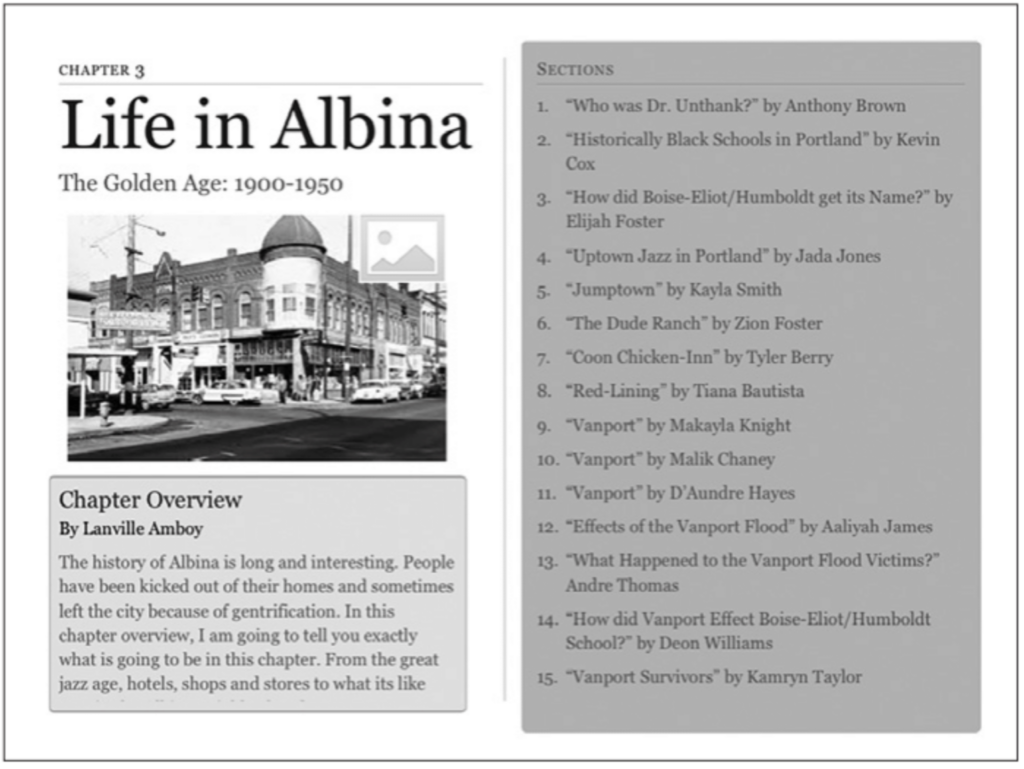

In language arts, students began by choosing their topics. If we wanted a book that told the truth and sang justice, we knew kids were going to have to love their topics. To prepare, Becky pulled out all of the readings, images, and classwork from the past two months, and then asked students to do the same as they entered class.

“What histories live in our neighborhood that shouldn’t be forgotten?” she asked. “What do we want new people in the neighborhood to know about how gentrification has happened in our neighborhood?” She asked students to reflect on their own as they looked through their body of work. After a few minutes, she broke the quiet of the room and asked students to begin writing names of people, places, or events that were possible chapters for our book.

She circulated, noticing what students were scribbling.

Jayla wrote: Aunt Vera, Williams Avenue

Jada wrote: jazz, Cotton Club, Vanport, Dr. Unthank

Zion wrote: I-5 freeway project, the Rose Garden

Malena wrote: eminent domain, Legacy Emanuel Hospital

When most students had finished, Becky directed them: “In a moment, I would like you to get up and move around the room. Read your lists with a few different people and then decide on the story you really want to write.”

Chairs scraped and the room got loud. Students shared their lists and began to discuss their topics. To encourage students to say more about their topics and stay focused, Becky wrote two sentence starters on the board:

I want readers to know. . .

This topic is important to tell about because. . .

“I want to write about Vanport because so many people died,” Michael told a friend.

“I want readers to know that only white men got free land from the government in the Donation Land Act,” Zion decided.

Eventually, discussions petered out and students returned to their seats. Becky projected a document titled “Albina Research Topics” and instructed students: “When you’re ready, raise your hand and I’ll write your topic on the board.” What emerged was the rough draft of the table of contents of our book, Albina Stories. It was fairly evenly divided between important historical places that showed the historic culture of the neighborhood, racist and unfair policies that paved the way for our neighborhood’s destruction, and biographies of people who worked for change. Students were curating the story of who had been left out and who benefited.

As we dug into the nitty-gritty of research and writing, Becky encouraged a few students to craft a foreword and an afterword to our historical compilation. These students had stepped up to the plate as leaders in this conversation and appeared ready to help guide their peers. Becky asked them to read the foreword and afterword of The History of Portland’s African American Community, and to think about the purpose of these parts of a book. What do authors try to get across to their readers and how do they reflect on their own research?

A few days later, Becky sat down to read what Cayden had written:

This book was written to enlighten people of the history of Portland and explicitly the Albina neighborhood. It goes back to before Oregon was a state and ends in 2014. Our research has come from a wide array of sources, from articles and essays to images and journals. This book isn’t just informative, it has the views of the writers and their feelings about the topic. Whether it’s gentrification or eminent domain, our views of right and wrong are expressed.

Prejudice and discrimination against the minorities in Portland started before Oregon was even a state. Whites who wanted nothing to do with African Americans moved out west. . . One of them remarked that he had come to Oregon to get rid of “saucy free Negroes.” When Oregon became a state, the legislative committee created exclusion laws to keep African Americans from living in Oregon. Although these laws are no longer a part of the state constitution, we still feel the effects of this unequal treatment.

Cayden’s writing was reflective of what powerful research does: It makes us question our assumptions by voicing truth, not just facts. Classroom research is about how teachers and students relate to the world, about developing an informed voice and working together to question, to challenge, to talk back, and to encourage change.

“Know Your History”

The final product was a sleek multimedia project that included video interviews, short narratives, informational articles, and an abundance of pictures. Fifty-eight different projects filled the “pages” of the digital book. But months slipped by, and we realized we had never actually sent it out into the world or asked students to turn their knowledge, opinions, and emotions into action.

“We’re going to circle back to something we did a little while ago,” Jeff said, as he pointed to the iPad cart in the corner. “Get a partner. Send one student per group to the cart to grab an iPad.”

He handed each student a graphic organizer with instructions for how to access the Albina Stories iBook. The plan was to reacquaint students with the contents of the book, get them to draw connections between a few articles, and ask them how they would get someone else excited about the articles. The students had other ideas.

“Tiana! Read mine!” MyKayla shouted across the room.

“I can’t believe I wrote that! Are we going to get to work on these?” asked Tiana.

“Sure, if that’s what you decide to do,” Jeff responded.

“My name is spelled wrong!” complained Malik.

“This looks really nice,” said Alexis.

After fighting the momentum and trying to pull students back to the graphic organizer, Jeff decided to step back and watch. The classroom was loud, it was buzzing, the students were on task, and the graphic organizers were getting done, slowly.

What was supposed to be a half-hour lesson turned into 50 minutes, and Jeff wrapped up by bringing the class back together and assigning a task to keep the project on track: “This is a remarkable book. You all did incredible work. How do we get people to read it? Throw out some ideas, and let’s make a list. You can do anything you want, as long as it is focused, and as long as it promotes Albina Stories.”

It felt risky giving students so much freedom, but the ideas that came back were solid. Yes, there were a few student groups that decided to “make a poster,” but the vast majority took divergent and exciting paths—a letter to President Obama and our district superintendent, social media promotion, t-shirts and hats promoting the book and expressing opinions on gentrification. For some groups, the poster turned into an opportunity to canvas the neighborhood, staple fliers to telephone poles, and hand them out on the street. “Gentrification destroys communities!” exclaimed Jasmine’s poster.

Alexis decided on letter writing. In a letter to President Obama, she wrote about our school, the negative impact of gentrification, and Albina Stories. Then she hammered it home with specific policy requests, advocating for fair housing laws and rent control. In another letter, to the Portland superintendent of schools, she requested that the school district use our book to teach the history of race in our city.

One group decided to use the opportunity to fundraise for our school’s end of the year activities. They baked a ton of cookies, made 50 fliers advertising Albina Stories, and based themselves outside Jada’s mom’s beauty shop, located a handful of blocks from the school. They raised more money in an hour and a half than any of our in-school fundraisers.

The students returned to school buzzing about the conversations and connections they had experienced.

“Mr. Waters, come look at this,” Chris called from across the computer lab. Chris, Kareem, Malik, and Michael were huddled around the screen.

“What is it?” Jeff asked.

“It’s our Facebook page for the book. We have more than 100 likes.”

“How many of those are students at our school?”

“Not very many. Some are from other schools. Some are people we don’t even know,” said Kareem. Even the local neighborhood association expressed an interest in sharing the book on their website.

At our spring open house and 5th-grade night, Becky set up her classroom with computers so students could share Albina Stories with parents and families. Families hovered over the devices, flipping through pages, as students explained the interviews, pictures, and essays.

Throughout the unit, we had struggled to answer the question “To what end?” Through the community action project, this came into focus. We had helped students understand the history of racism in our city, brought their families into the process, given them space to reflect on their own experiences, and helped them take responsibility and feel empowered.

The quality of student work argues against the narrative of a failing school and disengaged students of color. As students and their families continue to be forced to move miles away from the historical Black center of Portland, our students joined their voices with many other local activists and community members to expose the policies that support the rich and white in our community, and punish people of color. Our middle schoolers became community changemakers.

Resources

Boise-Eliot/Humboldt School. 2015. Albina Stories. goo.gl/9pFWaO.

Gibson, Karen J. 2007. “Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940-2000,” Transforming Anthropology. kingneighborhood. goo.gl/1137KV.

Pappas, Peter. 2014. Portland’s Japantown Revealed. itunes.apple.com/us/book/portlands-japantown-revealed/id887076348?mt=13.

Oregon Public Broadcasting. 1999. Local Color. goo.gl/PVX8B.

Parks, Casey. 2012. “Fifty years later, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center attempts to make amends for razing neighborhood.” Oregon Live. oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2012/09/post_273.html.

Portland Bureau of Planning. 1993. The History of Portland’s African American Community, 1805 to the Present. multco.us/file/15283/download.