Preview of Article:

“The Most Gentrified City of the Century”

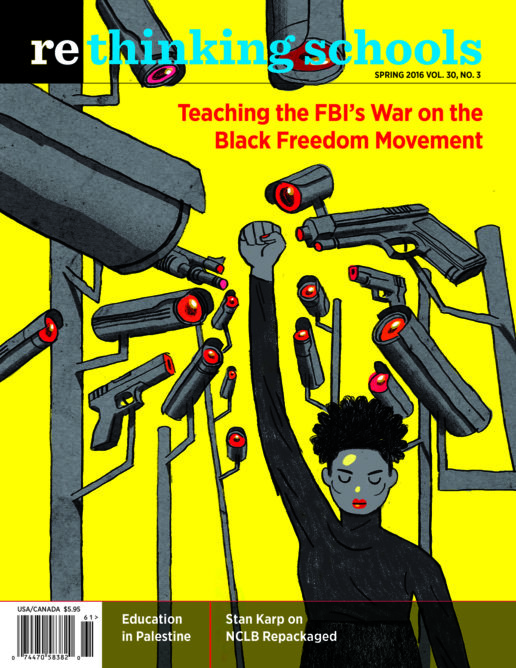

Illustrator: Chris Kindred

Boise-Eliot/Humboldt School is a special place. It stands, 90-year-old red brick and mortar, amongst newly constructed condos, craft breweries, and combination laundromat-bars, just a block off historic Mississippi Avenue in the Albina area of North Portland, Oregon. It is an obstinate place that, despite its decreasing enrollment and “level one” Oregon State School Report Card status, has survived two separate school closures and simply refused to yield to the forces of gentrification.

A recent article in Governing: The States and Localities described Portland as “the most gentrified city of the century,” and the vast majority of the gentrified tracts are in North and Northeast Portland. Although North Portland’s demographics have drastically changed over the last two decades, from predominantly African American to predominantly white, Boise-Eliot/Humboldt’s student population hasn’t. In a neighborhood that is mostly white, we serve the largest volume of African American students in the state. Less than half of the students who live within our district boundary attend our school, and less than half of our student population lives in our neighborhood.

As gentrification has forced out many working-class families of color, affluent white families, who often choose to opt out of the neighborhood’s “failing” public schools, have moved in. Many of the students we teach at Boise-Eliot/Humboldt travel long distances, riding public transportation from far in East Portland, to attend our historically Black school. Families often use the addresses of aunties, grandmas, and friends to ensure that their sons and daughters will continue a legacy that sometimes dates back to the flood of 1948, which destroyed the World War II shipyard-worker city of Vanport and pushed its largely African American population into the Albina area.

The mechanisms of segregated housing—unfair lending practices, exclusionary laws, eminent domain, urban renewal, and gentrification—are not distinct to Portland. These racist laws and practices continue to affect communities nationally. Our school, our neighborhood, and our students are part of a larger story, a larger conversation. Because this history is so relevant to our students’ lives and is often ignored by traditional curriculum, we decided to co-teach an integrated language arts/social studies unit on gentrification and neighborhood history to our 8th graders.

We hoped this unit would say: Yes, you’ve lived this. You are living this. Your experiences are important. And, in the face of a changing community, you have something to share that is irreplaceable. You have the opportunity to educate our community and neighborhood about a destructive process that we’ve all been part of.

We wanted to help students wade through Oregon’s often ignored racial history, and to help them feel empowered to go beyond the facts and into the messiness of evaluation and activism. What resulted was a yearlong process that included facilitating structured student discussions; interviewing families; lots of reading and writing; self-publishing a digital multimedia book about the history of race in our state, city, and neighborhood; and a student-driven community activism project.

“Those Fancy Apartments Are Going Up All Over”

We decided to launch our unit with a general overview of gentrification—What is it? How has our neighborhood changed?—and students’ personal narratives. We wanted to show students that this unit was deeply rooted in their own experiences. Moreover, we hoped to encourage students to find their own voices to talk back to discriminatory practices.

In his social studies class, Jeff began with a simple definition: “Gentrification is a change in a neighborhood,” he said, writing the sentence as a bullet point on a note sheet beneath the document camera. The students dutifully copied the sentence in the notes section of their social studies notebooks. “Our neighborhood has gone through gentrification. A lot of you grew up here. How have you seen it change?” Jeff asked the class.

The students looked up from their notes, and a few hands went halfway up. “The New Seasons [a high-end grocery store] is new. Does that count?” asked Jada.

“Absolutely, that’s a change. Let’s write it down.” Jeff wrote a second bullet in the notes: “How has our neighborhood changed?” and beneath it he put a dash and wrote “New Seasons Market.”

A few more hands shot up. “There are a lot more white people,” stated Jayla. “I’m not trying to be racist, but I was walking down Mississippi and I didn’t see any Black people at all, and it didn’t used to be like that.”

“They tore down that one bar; what was it called?” asked Aaliyah.

“LV’s 22? Wasn’t that it?” offered Jayla, leaning forward in her seat.

“That’s interesting. What are they building in its place?” Jeff prodded.

“Probably some of those fancy new apartments. They’re going up all over, down Mississippi and Vancouver and Williams,” said Jayla.

Jeff added “a lot of new buildings” to the list as students named more changes they had seen in the neighborhood. MyKyla talked about her family moving. Jordan said the butcher shop no longer carried certain items, like oxtails, that her grandma wanted. Hailey mentioned that Self-Enhancement, Inc. (a Black community-focused charter school and community resource) had moved its services out to East Portland—or, as our students call it, “The Numbers” (a reference to street names like 157th Avenue). Aaliyah talked about the new bike lanes on Vancouver and Williams, major thoroughfares a few blocks from the school. It just kept coming. After a substantial list was created, we organized our experiences into three categories: people, physical structures, and community services.

“But gentrification isn’t any old change,” Jeff said. “It impacts certain people more than others, doesn’t it? Jayla, what did you notice about race in our neighborhood? Can you connect that to gentrification?”

“Well,” Jayla began, “it seems like the people who were already here, Black people, have been hurt more.”

Later, we would discuss specific aspects of Portland’s development, like using eminent domain to force people of color and low-income families out of their homes. But the students seemed ready to write, and Jeff introduced the first assignment of our unit—the personal narrative: “We’ve all seen or experienced at least one aspect of gentrification, but many of our families have been here for generations.”

“My great-grandma went here!” shouted a student.

“Over the weekend you are going to interview your parents, grandma, auntie, someone you live with, about your family’s experiences with gentrification. You can ask them whatever you want, but there are a few questions that you have to ask. Turn your notebooks to your writing section and let’s get them written down. What section?”

“Writing!” came a chorus of voices.