Preview of Article:

The Morning After The Morning After

The following is from the book Forever After: New York City Teachers on 9/11. The book is dedicated "To the NYC teachers of 9/11 who kept our children safe... and to teachers everywhere whose stories of day-to-day commitment are seldom told." In the selection below, Michelle Fine describes the issues faced by U.S. Muslim-American youth following not only 9/11 but the U.S. invasion of Iraq.

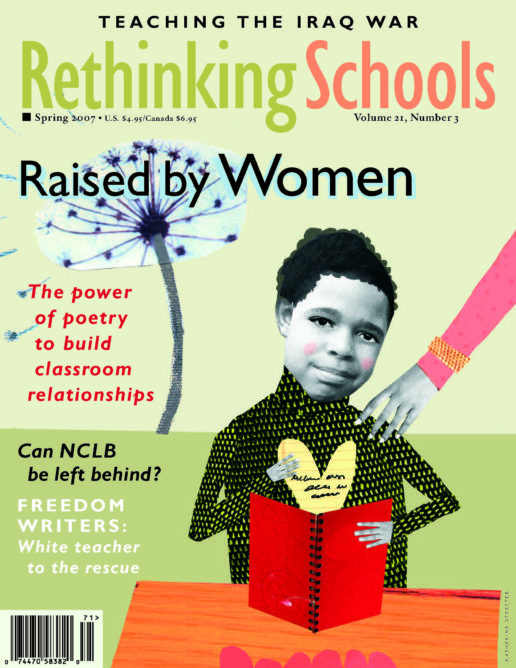

Illustrator: Omar