The Military Invasion of My High School

The role of JROTC

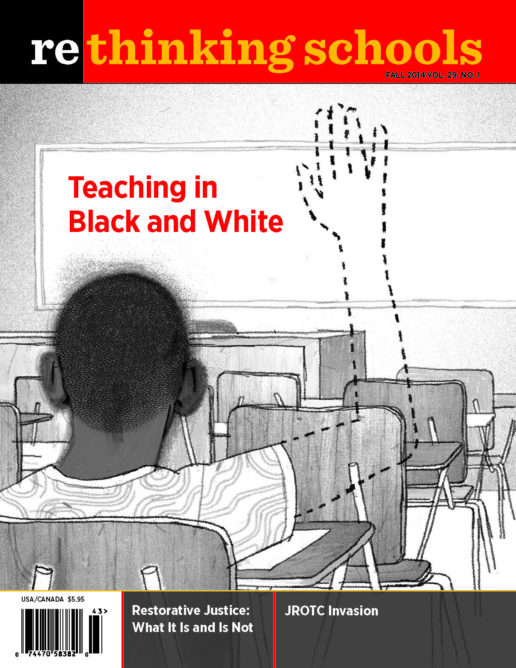

Illustrator: Hermes Crespo

U.S. Navy photo by Hermes Crespo

“Will you please write me a letter of recommendation for the Navy, Ms. McGauley? You’re my best class.” Thanh was enrolled in the recently established Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC) at our high school and he, like many of my students, was enamored with the military’s alluring promises of a magic carpet ride away from poverty and uncertainty.

My heart ripped as I listened to Thanh’s plea. I want to do what is best for my kids. I want to support and honor them in making their own informed decisions. But, given the impact of JROTC at our school, I felt very uneasy about the balance of information students like Thanh were receiving about enlistment in the U.S. military. After much discussion with Thanh, I wrote an honest letter, emphasizing his sensitive poetic nature and his commitment to fairness. The Navy eagerly welcomed him.

The sprawling campus of Reynolds High School (RHS), the second largest high school in Oregon, rests atop a ridge at the entrance to the scenic Columbia River Gorge in tiny Troutdale, 17 miles east of downtown Portland. When I first started teaching here 23 years ago, Reynolds was an almost all white, working-class, conservative, sub-rural community, culturally distinct from its larger urban neighbor. As Portland has become more gentrified, lower rents have attracted numerous low-income families—immigrant, African American, Latina/o, and white. Today, the Reynolds School District is a high-poverty, culturally diverse district with two of the poorest elementary schools in the state—perfect prey for military recruiters who win points for filling the coffers of the poverty draft.

During the Vietnam War era, much was written about JROTC’s role in teaching military training; today JROTC high school (and even middle school) programs incorporate a broader curricular agenda and are expanding rapidly. Yet, within the education community, little has been written about the implications and effects of JROTC in schools.

The potent presence of the military at RHS shines a floodlight on educational inequity. One sees college recruiters walking the halls of affluent Lincoln High School near downtown Portland. At RHS, college recruiters are few and far between, but military recruiters, JROTC commanders, and ASVAB (Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery) testers clamor to establish daily contact with potential recruits.

All too often I hear the refrain: “Well, the military is a good option—or perhaps the only option—for many kids.” As educators, we must ask critical questions: Whose interests do we ultimately serve by welcoming the military into our poorer schools? Is it really in any of our students’ best interests? What are the qualifications of the instructors? What does the JROTC curriculum actually teach our students?

JROTC 101

The National Defense Act of 1916 established JROTC to increase the U.S. Army’s readiness in the face of World War I. The ROTC Vitalization Act of 1964 directed the secretaries of each military branch to establish and maintain JROTC units for their respective branches. In the 1990s, the programs began expanding rapidly throughout the country. Today, there are approximately 3,500 Army, Air Force, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard JROTC units in schools in the United States and its territories. Last year, Congress instructed the secretary of defense to expand further and to report on “efforts to increase distribution of units in educationally and economically deprived areas.”

JROTC is not about education. But by housing recruiters and JROTC in public schools and offering them carte blanche privileges, we provide them a cloak of legitimacy. Militarism was one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “giant triplets” of societal destruction (along with racism and extreme materialism), yet today it appears as a legitimate component of the educational system—most often at underfunded schools.

At our school, JROTC is an actual school within a school, one that offers four levels of classes for which students earn full credits. It meets state requirements for career training. At RHS and many other schools, it is accepted as a substitute for physical education. Our JROTC instructors have also given make-up credit for writing and study skills classes, using online programs in the main JROTC classroom. The RHS program is directed by Brian James, a retired colonel from the Oregon Army National Guard, who tells me he looks forward to being able to offer health, history, and government credits as well.

Promoting Gun Culture at School

RHS has embraced school-based initiatives, including a commitment to restorative justice and peer mediation, that teach and encourage students to resolve conflicts nonviolently. JROTC’s militarism runs counter to these programs. Schools across the country are employing a variety of methods to curb bullying and violent incidents, create safe learning environments, and teach peaceful means of conflict resolution. JROTC’s introduction of weapons training, its partnership with the NRA to sponsor marksmanship matches, and its modeling of authoritarian militaristic solutions to problems contradict the schools’ stated opposition to violence.

Critics have been successful in getting JROTC to discontinue the use of live weapons in schools on a national level, but units continue to use air rifles for target practice at RHS and numerous other schools. Organizing makes a difference. In San Diego, for example, the Education Not Arms Coalition, made up of students, teachers, parents, and community groups, successfully removed target practice with air rifles from San Diego JROTC programs in 2009.

One School’s JROTC Story

In 2011, a former RHS principal, with the support of the school board and many staff members, laid down the red carpet for JROTC to create a program at our school. The JROTC contract requires the hiring of a minimum of two retired officers for the first 150 students enrolled as cadets. After 150, another instructor must be hired for each additional increment of 100 cadets. James and other retired military personnel teach courses in military science, called Leadership Education Training (LET), during the school day.

Three full-time JROTC instructors lead 13 sections of LET 1, 2, and 3 to 280 students. Last year, a new principal tried to make the JROTC class loads comparable to other teachers’ loads by laying off one of the commanders. Although the effort failed, James says he does not plan to ask for additional staffing at this time: “Even though I won that fight and she’s gone, it’s political. I’m a laid-back kind of guy, but if you push me into a corner, I’ll fight back and I’ll win. . . . I brought in the superintendent and the school board, the mayor of Troutdale, and the commander at Fort Lewis. We’re all still here, and she’s gone.”

James adds that they really should have a fourth officer since their “job is bigger than a teacher’s. We teach, mentor, and coach kids, and we take them on excursions. We take them to Florida and other places for rifle competitions.” Every teacher I know teaches, mentors, and coaches students; and if we had the Pentagon’s money, we would take them on many more excursions.

At RHS today, student loads for most non-JROTC teachers hover between 180 and 220 students (more than twice the load of the JROTC instructors) with class sizes in the 30s and low 40s. JROTC cadets often take LET in place of physical education, and a single PE teacher would normally support 250 or more students. If JROTC were eliminated at RHS, the district would hire fewer than half as many teachers to replace them—although it would be wonderful for our students if we, too, had student loads of 70 to 90. In general, the federal subsidy covers less than half the total salaries and none of the employment taxes or benefits for JROTC instructors. Schools wind up using extra money from their budgets to, in effect, subsidize a high school military training/recruiting program for the Pentagon.

JROTC instructors are not certified in the same way as other school district teachers. In some states they are not required to have more than a GED (although the commander must have at least a BA). Generally, the military decides who is qualified to be a JROTC instructor and then presents them to the school district for hiring. According to James, each of the three JROTC instructors at RHS has at least a BA. He says getting certified to teach in the program is “a double whammy because we have to be certified by both the state of Oregon and the Army.” (There is no required teacher training; Oregon simply requires JROTC instructors to take a test on the history of discrimination in Oregon.)

Teaching Militarism, Not Critical Thinking

The Reynolds LET 1 course description apprises students that they will learn “leadership, follower, and citizenship skills.” JROTC is military training. Instead of teaching toward a just and peaceful world, military training emphasizes dominance and nationalism. In fact, once students enlist in the military, they are no longer guided by the United States Constitution. Rather they are governed by the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

The Pentagon contracts with Pearson to write JROTC curriculum, including social studies, health, and leadership textbooks. The local school district has no control over their content. No process exists for regular certified staff to review JROTC materials for appropriateness, accuracy, or conformity to educational standards.

Teachers focused on social justice are critical of the historical perspectives of many mainstream textbooks. But, because the JROTC curriculum is focused on developing leaders for the U.S. military, there is a specific danger to these texts. For example, Lesson 2 of the LET 3 textbook is titled “Ethical Choices, Decisions, and Consequences.” The authors compare and contrast the Vietnam and Iraq Wars. They state that the sole cause of the Vietnam War was containment of communism: “American military personnel began deploying to Vietnam in 1954 to strengthen the country against communist North Vietnam.” The authors cite then-President Johnson’s 1964 statements that North Vietnam attacked a U.S. destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin as the impetus for the broader war, ignoring overwhelming evidence from declassified documents that there was no such attack.

The narrative continues: “The United States went to war in Iraq as part of its global war on terrorism.” In the same paragraph, the authors introduce Osama bin Laden and explain the creation of al-Qaeda “to dislodge American forces in the Middle East.” The implication is clear—Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden were working in cahoots to attack the United States. To further cement this alleged relationship, which did not exist, they quote George W. Bush: “Iraq could decide on any given day to provide a biological or chemical weapon to a terrorist group or individual terrorists. Alliance with terrorists could allow the Iraqi regime to attack America without leaving any fingerprints.” Nowhere in the case study or various historical timelines do the authors indicate that both Hussein and bin Laden were at one time strongly supported by the United States. Describing the arguments for the second Gulf War, the text notes a “lack of indisputable evidence” (as opposed to the presence of manufactured false evidence) that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.

In outlining alternatives to these military invasions, the authors identify the only potential consequences as unacceptably negative. In the case of Vietnam, they cite the “domino theory,” which predicted one country after another becoming communist threats to the United States. In the case of Iraq, they quote then-President Bush without additional commentary: “We cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.”

Lesson 3 is on “Global Citizenship Choices, Decisions, and Consequences.” The authors discuss intelligence as a tool of U.S. foreign policy: “The CIA focuses mostly on countries it thinks might be unfriendly. . . . Sometimes intelligence agencies have helped overturn the government of a country. . . . For example, the CIA took part in overthrowing the government of Salvador Allende. The United States government thought Allende was not favorable to our national interest. Like defense, diplomacy, foreign aid, and trade measures, intelligence is an important tool of foreign policy.” There is no questioning of the U.S.-led coup against the democratically elected president of Chile, nor is there any discussion of the consequences and implications of the decision.

“The greatest purveyor of violence…”

The sole mission of the U.S. military is to prepare for and fight wars. JROTC in middle and high schools, ROTC in colleges, the ASVAB test, military partnerships with schools, research and development programs—all are designed as tools for fulfilling this goal. Military recruiters and JROTC personnel are notorious for not disclosing the whole truth and for making seductive promises—verbally and in writing—that can be broken at any time. For example, students and staff are often told that undocumented students will receive legal citizenship papers if they enlist. This is false. By law, undocumented immigrants may not enlist in the U.S. armed forces, or even enroll in JROTC. (Documented immigrants may enlist and can receive citizenship status for doing so if they fulfill all requirements. Last spring Pentagon officials approved a policy that would allow a limited number of undocumented young people “with critical language or medical skills” and who came to the United States as children to enlist in the military, opening a pathway to eventual citizenship.)

JROTC is a component of the U.S. military apparatus, what King called the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”—and nothing about the current world situation would encourage him to modify that statement. As educators, we need to teach students to read the world, to question, and to critically analyze the history of U.S. militarism. And we must get JROTC out of our schools.

In June, after this article had been accepted for publication, an avid (and apparently mentally unstable) JROTC student at RHS armed himself with a semi-automatic rifle and pistol, a knife, and hundreds of rounds of ammunition. He fatally shot one student and injured a teacher before police cornered him and he took his own life. This tragedy highlights the importance of closing down programs that feed violent tendencies in vulnerable students and contradict school-based efforts to teach nonviolent conflict resolution.