The Importance of Goodbye

When Students Leave Midyear

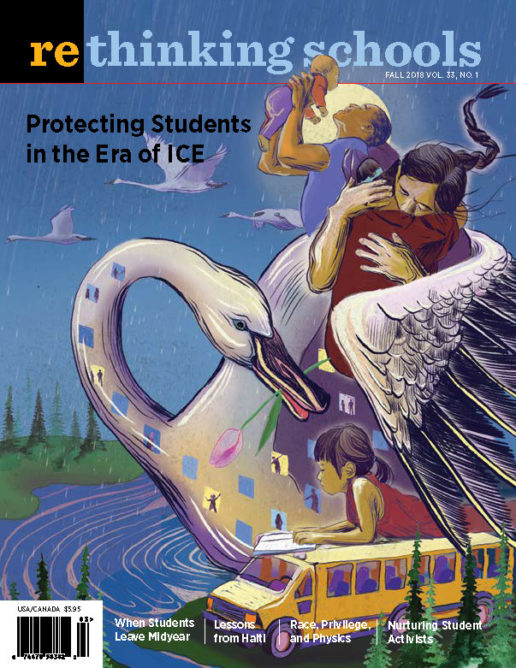

Illustrator: Celia Jacobs

A scene from my women’s studies class last year: Students are discussing the upcoming school election about whether to change the homecoming court from the gendered “princesses” to an ungendered “royalty court.” Katie, a Korean American sophomore, is sharing her insights. She beautifully describes her support for the change and a nagging unease with all the other gender binaries left unaddressed within school culture, including policies, practices, and curricula. I tell the class how impressed and moved I am by Katie’s wisdom.

“This is one issue where my students really do know more than I, speak more fluently than I, and where we teachers desperately need to let ourselves be guided by your generation,” I offer. Katie’s eyes fill with sparkly tears. She says, “Wow. That’s so nice. Thank you.” In the moment, I interpret Katie’s emotion as tied to the poignancy of the discussion or to the unexpected outpouring of praise she has received from me. A few minutes later, I suspect otherwise.

As my students read an essay about implicit bias, I open my school email to see a message from the counseling secretary with the subject: “Withdrawal back to Korea”

Yeun, Chae-won

886712

Last day will be Tuesday, 9/26/17. Please provide a numeric withdrawal grade and any fines or fees.

Thanks!

I swallow. Chae-won Yeun? No, that can’t be.

I look up at my students, their brows furrowed with concentration as they read, highlighting and energetically scribbling comments in the margins of their text. I scan the faces and stop at Katie’s. Like so many other Korean American and Chinese American students at my school, she goes by an “American” name, a practice that seems to say everything about how deeply committed hegemonic U.S. culture is to erasing Asian American identity. My throat tightens as I helplessly check my class list to confirm what my gut already knows: Yes, Katie is Chae-won. Yes, it is she the email is about. Katie will come to my Women’s Studies class only one more time before she moves to Korea.

At the end of class, I approach Katie as she packs her bag. I say, “Katie, I just got an email that is breaking my heart. Is it true you are leaving next week?” Katie smiles an unhappy smile. It is sad with a hint of . . . shame? Embarrassment? Uncertainty? My mind is racing.

And what I say next is poorly considered and ill-advised, but my heart overtakes my head, and as tears fill my eyes, I blurt, “Why?”

Katie is forgiving of my nosy indiscretion. She looks at me with what seems like pity, and says, “Well, it’s complicated. We don’t want to go. But . . . you know, my parents are having some issues with their visas.” I make eye contact and nod. I say, “Understood.”

I swallow my grief and shock and tell Katie how much I love her, how much I appreciate her fierce intelligence, her enthusiastic engagement with the curriculum, and her generosity of spirit in class discussions. I tell her how much I am going to miss her. I tell her that I am so, so, so sorry that she and her family do not feel they can stay in this country. I tell her that I want to stay in touch. And then I ask if we can share with the class that she is leaving. I say, “I want to honor your departure and give your classmates a chance to say goodbye.” She agrees.

The Tale of Two Jesses

At the suburban, affluent high school where I have taught for 17 years, student departures midyear are relatively rare and, most of the time, I do not find out until they are gone.

Sometimes this is the student’s choice because saying goodbye is fraught and hard. Sometimes it’s because tragedy has struck — a student is hospitalized for attempting suicide, gets in trouble with the law, or a custody dispute has forced a move. Sometimes parents act quickly after a bad report card in hopes of finding a better fit for their child. Whatever the reason, the classroom is unexpectedly and suddenly reconfigured and I am left to figure out how, if at all, to disclose and discuss the departure.

Some years back, I taught what was, for my school, an atypically diverse, sophomore-level U.S. history and government class. It was relatively small (26 students) compared to my other classes (normally 32 students), with four students from our autism program, a handful of students identified as Talented and Gifted, three English language learners, a couple of seniors who had failed the class earlier in their careers and were back to give it another go, a girl whose hearing and speech were severely impaired by cancer, a transgender student, and an array of other wonderful kids.

We became a particularly close-knit bunch. In our daily current events discussions, almost everyone spoke; we had inside jokes; we took care of each other.

One member of this class was Jesse, a white, 16-year-old girl. She was new to our school, after having dropped out of her previous school due to crippling depression and anxiety. Her appearance was Sex Pistols, but her affect was timid and insecure. She struggled with performing (writing, speaking) on demand, but did OK in small groups. Since she struck up in-class friendships with a handful of other students with whom she seemed comfortable and at ease, I was optimistic.

But by the end of November, Jesse was struggling. She was missing a lot of school. She was depressed and angry, often lashing out at me (and other teachers) for reasons I did not grasp. One time she stomped out in the middle of class. When I checked in with her later, she said, “You know what you did.” I truly did not. I pleaded with her to help me understand. She said, “Everyone saw how cruelly you looked at me.” I had no awareness that I had looked at her at all, much less cruelly. By December, Jesse was withdrawn to receive full-day psychiatric services.

Because of Jesse’s always-spotty attendance, it took a few weeks for students to remark on her absence. But eventually someone asked, “Hey, where’s Jesse?” I said, “She doesn’t go to school here anymore, unfortunately.” It was a terribly inadequate explanation, but all I could think to safely say, without revealing information Jesse had not given me permission to share. Not a single student asked for any additional information. They seemed to know it was something we could not discuss.

In that same class, in that same fall, I got a new student also named Jesse. This Jesse was 17, Black, and male, and he joined the class in early October after moving back to Oregon from another state. As a midyear addition, he had the burden of inserting himself into a class culture and community with its already-established patterns and practices. But Jesse was more than up to the task. Having moved schools a lot in his young life, he was an expert on being the new kid. He was warm, funny, charismatic, unafraid of saying the wrong thing, and he quickly built an identity in our class: The Questioner.

Once every couple of weeks, Jesse would lean back in his desk, sort of twist his body to face the rest of the students and say, “Let me ask you all a question . . .” Then he would open up some delicious political, moral, or economic can of worms for the class to consider and address.

But like female Jesse, male Jesse also had a fraught backstory. He had spent a number of years in foster care and though he had recently been adopted, I was told he had suffered untold loss and trauma in the preceding years. He also had a parole officer.

Through the remainder of the fall and into winter, Jesse seemed to be doing all right. He had a girlfriend; he was deeply interested in Black history; he participated in our school’s discussions of diversity and racism, speaking publicly and bravely about being the recipient of multiple racial microaggressions on campus. But he was also hanging out with kids who smoked weed, and while this didn’t make him so different from other kids at the high school, for Jesse, getting caught using illegal drugs would be a violation of his parole. So I, like many of the adults looking out for Jesse, was worried.

By spring, Jesse had been taken out of school. The story was a bit convoluted, but from what I understood, he’d missed a check-in with his parole officer, and a judge ordered him to juvenile detention. Once again, I was confronted with a student’s question: “Hey, what happened to Jesse?” Once again, I felt forced to offer the most unsatisfactory of answers: “Unfortunately, he’s not going to school here anymore.” This time, there was a follow-up. Carter, a confident student whose life plans include becoming president of the United States, asked: “Where did he go?” I shrugged and lied, “I am not really sure.” I added the very truthful “But I miss him.”

As the school year ended, my fourth period had a lot to be proud of — we were good to each other, we worked hard, we forgave each other’s worst tendencies, we had a bevy of powerful essays and narratives proving our commitment to understanding a deeply complicated world. But we were down two Jesses, two people who had wholly been part of our class family, yet we had no monument to their existence, no way of marking that though we were now only 24, we had once been 26.

Woman of the Day

Katie’s last day rolled around too quickly. In my women’s studies class, we always open the period with a 10-minute Woman of the Day discussion, a way of highlighting and addressing how underrepresented women are across the curriculum by profiling an artist, activist, athlete, politician, philosopher, scientist, or historical figure. On this particular Tuesday, I changed it up a bit.

“Today our Woman of the Day is actually one of you. Today our Woman of the Day is Katie, because today is her last day in our class,” I said. The class erupted in gasps and exclamations of “What?!” Katie shyly looked up from her desk and said, “Yeah, it’s true. Today is my last day. My family is moving to Korea.” Katie seemed uncertain about saying anything more, so I jumped back in, “So Katie is our Woman of the Day because she has blessed our discussions with her brilliance, honesty, wit, and humor. She has been an integral part of our class identity. And I can’t say enough about how much I am going to miss her.” Katie’s seat partner, Monica, had tears streaming down her face.

In the midst of their shock, students blurted some hard questions: “Why?!” “Are you coming back?” “Is it for your parents’ work?” After a few gracefully evasive answers, Katie’s classmates gave up on the interrogation and simply shared some love. Annie said, “I can’t imagine this class without you!” Tiffany said, “Who am I gonna speak Korean with?” With what I hope was a bit of good-natured hyperbole, Sarah said, “I cannot believe you’re only a sophomore; I have learned more from you in this class than in all four years of high school combined.”

As class finished, students formed a line at Katie’s desk, hugging her, wishing her well, and saying goodbye. Eventually Katie packed up and handed me a small gift and note; we hugged and said a teary farewell. I looked up to see Veronica, a senior girl, lingering at the back of my room. I could tell she wanted to talk so I gave her an excuse to stay by asking her to help me wipe down the desks.

Once everyone was gone, I said to Veronica, “What’s up?” She said, “Ms. Wolfe, do you know why Katie is leaving?” I shrugged and said, “Not really.” Veronica said, “Ms. Wolfe, is it because of Trump? Is it because of DACA?” I said, “Veronica, I really don’t know. But what I do know is that families just like Katie’s are being targeted by the president’s immigration policies and our class just got a taste of how unjust that is.” We talked for a bit longer as Veronica struggled to sort out her grief and confusion; ultimately she left with an honest, if imprecise, understanding of Katie’s leaving.

A Resolution

Because I was informed of Katie’s departure before it happened, I was able to prepare some comments, get her permission to share her leaving with the class, and mark the occasion in an appropriate and meaningful way. But most of the time, we teachers do not get this luxury.

When I discover that a student has suddenly and unexpectedly left the school, I almost always attempt to reach out to them through email or text to say goodbye, to share what I appreciated about them as students, to wish them well. I keep it brief, but I want to make sure my students know they matter. These notes are important, but their function is private; they do not accomplish what my women’s studies students experienced — a shared and communal marking of loss.

It is no accident that the three students discussed in this article belong to some of the United States’ most vulnerable groups: undocumented, mentally ill, Black. Indeed, there is a direct line to be drawn between the instability of their educational lives and their tenuous status in an unjust world. When I am silent about the terms of their departure, I feel dangerously complicit in reinforcing a social narrative that these lives don’t matter, that their education, their presence in our classrooms is expendable, inconsequential. How do I balance a desire to mark these departures in a meaningful way against the requirement to protect these students’ privacy?

The close of every school year brings with it resolutions for the next. Some of them are holdovers from the year before, goals that I can never quite master (“This year I will check my snark.”); some of them I have actually achieved (“This year I will return papers within one week.”). The two Jesses and Katie are the authors of this year’s resolution and this is one I will keep: This year I will find a way to recognize the loss to our classroom community of students who leave midyear.

I will say their names. I will share what I will miss about them. And I will show the remaining students that their presence matters, that should they ever have to leave, they too will be missed. They have left a mark on this school, this class, and this teacher.