The Human Lives Behind the Labels

The Global Sweatshop, Nike, and the race to the bottom

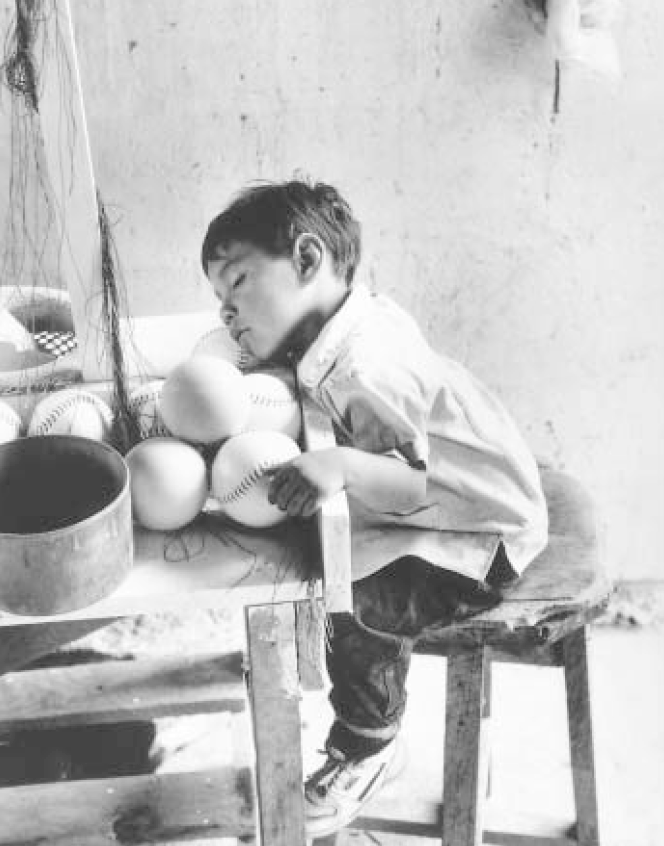

A small boy sleeps, sitting atop a stool where he helps his family make softballs in the Honduran village of Cholomo.

I began the lesson with a beat-up soccer ball.

The ball sat balanced in a plastic container on a stool in the middle of the circle of student desks. “I’d like you to write a description of this soccer ball,” I told my high school Global Studies class. “Feel free to get up and look at it. There is no right or wrong. Just describe the ball however you’d like.”

Looks of puzzlement and annoyance greeted me. “It’s just a soccer ball,” someone said.

Students must have wondered what this had to do with Global Studies. “I’m not asking for an essay,” I said, “just a paragraph or two.”

As I’d anticipated, their accounts were straightforward — accurate if uninspired. Few students accepted the offer to examine the ball up close. A soccer ball is a soccer ball. They sat and wrote. Afterwards, a few students read their descriptions aloud. Brian’s is typical:

The ball is a sphere which has white hexagons and black pentagons. The black pentagons contain red stars, sloppily outlined in silver… One of the hexagons contains a green rabbit wearing a soccer uniform with “Euro 88” written parallel to the rabbit’s body. This hexagon seems to be cracking. Another hexagon has the number 32 in green standing for the number of patches that the ball contains.

But something was missing. There was a deeper social reality associated with this ball — a reality that advertising and the consumption-oriented rhythms of U.S. daily life discouraged students from considering. “Made in Pakistan” was stenciled in small print on the ball, but very few students thought that significant enough to include in their descriptions. However, these three tiny words offered the most important clue to the human lives hidden in “just a soccer ball” — a clue to the invisible Pakistanis whose hands crafted the ball sitting in the middle of the classroom.

I distributed and read aloud Bertolt Brecht’s poem “A Worker Reads History” (included in Rethinking Our Classrooms, p. 91.) as a tool to pry behind the soccer-ball-as-thing:

Who built the seven gates of Thebes?

The books are filled with names of kings.

Was it kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?…

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? Imperial Rome

Is full of arcs of triumph. Who reared them up?…Young Alexander conquered India.

He alone?

Caesar beat the Gauls.

Was there not even a cook in his army?…Each page a victory.

At whose expense the victory ball?

Every ten years a great man,

Who paid the piper?

“Keeping Brecht’s questions in mind,” I said, after reading the poem, “I want you to re-see this soccer ball. If you like, you can write from the point of view of the ball, you can ask the ball questions, but I want you to look at it deeply. What did we miss the first time around? It’s not ‘just a soccer ball.'” With not much more than these words for guidance — although students had some familiarity with working conditions in poor countries — they drew a line beneath their original descriptions and began again.

Versions one and two were night and day. With Brecht’s prompting, Pakistan as the country of origin became more important. Tim wrote in part: “Who built this soccer ball? The ball answers with Pakistan. There are no real names, just labels. Where did the real people go after it was made?” Nicole also posed questions: “If this ball could talk, what kinds of things would it be able to tell you? It would tell you about the lives of the people who made it in Pakistan… But if it could talk, would you listen?” Maisha played with its colors and the “32” stamped on the ball: “Who painted the entrapped black, the brilliant bloody red, and the shimmering silver? Was it made for the existence of a family of 32?” And Sarah imagined herself as the soccer ball worker: “I sew together these shapes of leather. I stab my finger with my needle. I feel a small pain, but nothing much, because my fingers are so calloused. Everyday I sew these soccer balls together for 5 cents, but I’ve never once had a chance to play soccer with my friends. I sew and sew all day long to have these balls shipped to another place where they represent fun. Here, they represent the hard work of everyday life.” When students began to consider the human lives behind the ball-as-object, their writing also came alive.

Geoffrey, an aspiring actor, singer, and writer, wrote his as a conversation between himself and the ball:

“So who was he?” I asked.

“A young boy, Wacim, I think,” it seemed to reply.

I got up to take a closer look. Even though the soccer ball looked old and its hexagons and other geometric patterns were cracked, the sturdy and intricate stitching still held together.

“What that child must’ve gone through,” I said.

“His father was killed and his mother was working. Wacim died so young… It’s just too hard. I can’t contain these memories any longer.” The soccer ball let out a cry and leaked his air out and lay there, crumpled on the stool. Like his master, lying on the floor, uncared for, and somehow overlooked and forgotten.”

Students had begun to imagine the humanity inside the ball; their pieces were vivid and curious. The importance of making visible the invisible, of looking behind the masks presented by everyday consumer goods, became a central theme in my first-time effort to teach about the “global sweatshop” and child labor in poor countries. [I did an abbreviated version of this unit with my U.S. history classes. Some of the student writing here is theirs.]

Teaching About the Global Sweatshop

The paired soccer ball writing assignment was a spur-of-the-moment classroom introduction to Sydney Schanberg’s June 1996 Life magazine article, “Six Cents an Hour.” Schanberg, best known for his New York Times investigations of Cambodia’s “killing fields,” had traveled to Pakistan and posed as a soccer ball exporter. There, he was offered children for $150 to $180 who would labor for him as virtual slaves. As Schanberg reports, in Pakistan, children as young as six are “sold and resold like furniture, branded, beaten, blinded as punishment for wanting to go home, rendered speechless by the trauma of their enslavement.” For pennies an hour, these children work in dank sheds stitching soccer balls with the familiar Nike swoosh and logos of other transnational athletic equipment companies.

Nike spokesperson Donna Gibbs defended her company’s failure to eliminate child labor in the manufacture of soccer balls: “It’s an ages-old practice,” she was quoted as saying in Schanberg’s article, “and the process of change is going to take time.” But as Max White, an activist with the “Justice. Do It NIKE!” coalition, said when he visited my global studies class last month, “Nike knew exactly what it was doing when it went to Pakistan. That’s why they located there. They went because they knew child labor was an ‘ages-old practice.'”

My initial impulse had been to teach a unit on child labor. I thought that my students would empathize with young people around the globe, whose play and education had been forcibly replaced with the drudgery of repetitive work — and that the unit would engage them in thinking about inequities in the global division of labor. Perhaps it might provoke them to take action on behalf of child workers in poor countries.

But I was also concerned that we shouldn’t reduce the growing inequalities between rich and poor countries to the issue of child labor. Child labor could be entirely eliminated and that wouldn’t affect the miserably low wages paid to adult workers, the repression of trade unions and democratic movements, the increasing environmental degradation, and the resulting Third World squalor sanitized by terms like “globalization” and “free trade.” Child labor is one spoke on the wheel of global capitalism, and I wanted to present students with a broader framework to reflect on its here-and-now dynamics. What I share here is a sketch of my unit’s first draft — an invitation to reflect on how best to engage students in these issues.

The Transnational Capital Auction

It seemed to me that the central metaphor for economic globalization was the auction: governments beckoning transnational corporations to come hither — in competition with one another — by establishing attractive investment climates (e.g., by maintaining low-wage/weak union havens and not pressing environmental concerns). So I wrote what I called “The Transnational Capital Auction: A Game of Survival.” I divided students into seven different “countries,” each of which would compete with all the others to accumulate “friendly to Capital points” — the more points earned, the more likely Capital would locate in that country. In five silent auction rounds, each group would submit bids for minimum wage, child labor laws, environmental regulations, conditions for worker organizing, and corporate tax rates. For example, a corporate tax rate of 75% won no points for the round, but a zero tax rate won 100 points. (There were penalty points for “racing to the bottom” too quickly, risking popular rebellion, and thus “instability” in the corporate lexicon.)

I played “Capital” and egged them on: “Come on group three, you think I’m going to locate in your country with a ridiculous minimum wage like $5 an hour. I might as well locate in the United States. Next round, let’s not see any more sorry bids like that one.” A bit crass, but so is the real-world downward spiral simulated in the activity.

At the game’s conclusion, every country’s bids hovered near the bottom: no corporate taxes, no child labor laws, no environmental regulations, pennies an hour minimum wage rates, union organizers jailed, and the military used to crush strikes. As I’d anticipated, students had breathed life into the expressions “downward leveling” and “race to the bottom.” In the frenzied competition of the auction, they’d created some pretty nasty conditions, because the game rewarded those who lost sight of the human and environmental consequences of their actions. I asked them to step back from the activity and to write on the kind of place their country would become should transnational Capital decide to accept their bids and locate there. I also wanted them to reflect on the glib premise that underlies so much contemporary economic discussion that foreign investment in poor countries is automatically a good thing. And finally I hoped that they would consider the impact that the race to the bottom has on their lives, especially their future work prospects. (That week’s Oregonian carried articles about the Pendleton Co.’s decision to pull much of its production from Oregon and relocate to Mexico.) I gave them several quotes to reflect on as they responded:

“It is not that foreigners are stealing our jobs, it is that we are all facing one another’s competition.” — William Baumol, Princeton University economist

“Downward leveling is like a cancer that is destroying its host organism — the earth and its people.” — Jeremy Brecher and Tim Costello, authors of “Global Village or Global Pillage”

“Globalization has depressed the wage growth of low-wage workers [in the United States.] It’s been a reason for the increasing wage gap between high-wage and low-wage workers.” — Laura Tyson, Chair, U.S. Council of Economic Advisers

Many global issues courses are structured as “area studies,” with units focusing on South America, sub-Saharan Africa, or the Middle East. There are obvious advantages to this region-by-region progression, but I worried that if I organized my global studies curriculum this way, students might miss how countries oceans apart, such as Indonesia and Haiti, are affected by the same economic processes. I wanted students to see globalization as, well, global — that there were myriad and far-flung runners in the race to the bottom.

This auction among poor countries to attract Capital was the essential context my students needed in order to recognize patterns in such seemingly diverse phenomena as child labor and increased immigration to the world’s so-called developed nations. However, I worried that the simulation might be too convincing, corporate power depicted as too overwhelming. The auction metaphor was accurate but inexorable: Students could conclude that if transnational Capital is as effective an “auctioneer” as I was in the simulation, the situation for poor countries must be hopeless. In the follow-up writing assignment, I asked what if anything people in these countries could do to stop the race to the bottom, the “downward leveling.” By and large, students’ responses weren’t as bleak as I feared. Kara wrote: “Maybe if all the countries come together and raise the standard of living or become ‘capital unfriendly’ then capital would have no choice but to take what they receive. Although it wouldn’t be easy, it would be dramatically better.” Adrian suggested that “people could go on an area-wide strike against downward leveling and stand firm to let capital know that they won’t go for it.” And Matt wrote simply, “revolt, strike.” Tessa proposed that people here could “boycott products made in countries or by companies that exploit workers.”

But others were less hopeful. Lisa wrote, “I can’t see where there is much the people in poor countries can do to stop this ‘race to the bottom.’ If the people refuse to work under those conditions the companies will go elsewhere. The people have so little and could starve if they didn’t accept the conditions they have to work under.” Sara wrote, “I don’t think a country can get themselves out of this because companies aren’t generous enough to help them because they wouldn’t get anything out of it.”

What I should have done is obvious to me now. After discussing their thoughts on the auction, I should have re-grouped students and started the auction all over again. Having considered various alternative responses to the downward spiral of economic and environmental conditions, students could have practiced organizing with each other instead of competing against each other, could have tested the potential for solidarity across borders. At the least, re-playing the auction would have suggested that people in Third World countries aren’t purely victims; there are possible routes for action, albeit enormously difficult ones.

T-shirts, Barbie Dolls, and Baseballs

We followed the auction with a “global clothes hunt.” I asked students to: “Find at least ten items of clothing or toys at home. These can be anything: T-shirts, pants, skirts, dress shirts, shoes, Barbie dolls, baseballs, soccer balls, etc.,” and to list each item and country of manufacture. In addition, I wanted them to attach geographic location to the place names, some of which many students had never heard of (for example, Sri Lanka, Macau, El Salvador, and Bangladesh). So in class they made collages of drawings or magazine clippings of the objects they’d found, and with the assistance of an atlas, drew lines on a world map connecting these images with the countries where the items were produced.

We posted their collage/maps around the classroom, and I asked students to wander around looking at these to search for patterns for which kinds of goods were produced in which kind of countries. Some students noticed that electronic toys tended to be produced in Taiwan and Korea; that more expensive shoes, like Doc Martens, were manufactured in Great Britain or Italy; athletic shoes were made mostly in Indonesia or China. On their “finding patterns” write-up, just about everyone commented that China was the country that appeared most frequently on people’s lists. A few kids noted that most of the people in the manufacturing countries were not white. As Sandee wrote, “The more expensive products seem to be manufactured in countries with a higher number of white people. Cheaper products are often from places with other races than white.” People in countries with concentrations of people of color “tend to be poorer so they work for less.” We’d spent the early part of the year studying European colonialism, and some students noticed that many of the manufacturing countries were former colonies. I wanted students to see that every time they put on clothes or kick a soccer ball they are making a connection, if hidden, with people around the world — especially in Third World countries — and that these connections are rooted in historic patterns of global inequality.

From here on, I saturated students with articles and videos that explored the working conditions and life choices confronting workers in poor countries. Some of the resources I found most helpful included: “Mickey Mouse Goes to Haiti,” a video critiquing the Walt Disney Co.’s exploitation of workers in Haiti’s garment industry (workers there, mostly women, make 28 cents an hour; Disney claims it can’t afford the 58 cents an hour workers say they could live on); a CBS “48 Hours” exposZ of conditions for women workers in Nike factories in Vietnam, reported by Roberta Baskin; several Bob Herbert “In America” New York Times columns; a Nov. 3, 1996, Washington Post article, “Boot Camp at the Shoe Factory Where Taiwanese Bosses Drill Chinese Workers to Make Sneakers for American Joggers,” by Anita Chan; “Tomorrow We Will Finish,” a UNICEF-produced video about the anguish and solidarity of girls forced into the rug-weaving industry in Nepal and India; and an invaluable collection of articles called a “Production Primer,” collected by “Justice. Do it NIKE!,” a coalition of Oregon labor, peace and justice groups.

I indicated above that the advantage of this curricular globe-trotting was that students could see that issues of transnational corporate investment, child labor, worker exploitation, poverty, etc. were not isolated in one particular geographic region. The disadvantage was that students didn’t get much appreciation for the peculiar conditions in each country we touched on. And I’m afraid that, after awhile, people in different societies began to appear as generic global victims. This was not entirely the fault of my decision to bounce from country to country, but was also a reflection of the narrow victim orientation of many of the materials available.

I was somewhat unaware of the limits of these resources until I previewed a 25-minute video produced by Global Exchange, “Indonesia: Islands on Fire.” One segment features Sadisah, an Indonesian ex-Nike worker, who, with dignity and defiance, describes conditions for workers there and what she wants done about them. I found her presence, however brief, a stark contrast to most of the videos I’d shown in class that feature white commentators with Third World workers presented as objects of sympathy. Although students generated excellent writing during the unit, much of it tended to miss the humor and determination suggested in the “Islands on Fire” segment and concentrated on workers’ victimization.

Critique Without Caricature

Two concerns flirted uncomfortably throughout the unit. On the one hand, I had no desire to feign neutrality — to hide my conviction that people here need to care about and to act in solidarity with workers around the world in their struggles for better lives. To pretend that I was a mere dispenser of information would be dishonest, but worse, it would imply that being a spectator is an ethical response to injustice. It would model a stance of moral apathy. I wanted students to know these issues were important to me, that I cared enough to do something about them.

On the other hand, I never want my social concerns to suffocate student inquiry or to prevent students from thoughtfully considering opposing views. I wanted to present the positions of transnational corporations critically, but without caricature.

Here, too, it might have been useful to focus on one country in order for students to evaluate corporate claims — e.g., “Nike’s production can help build thriving economies in developing nations.” I’d considered writing a role play about foreign investment in Indonesia with roles for Nike management as well as Korean and Taiwanese subcontractors. (Nike itself owns none of its own production facilities in poor countries.) This would have provoked a classroom debate on corporate statements, where students could have assessed how terms like “thriving economies” may have different meanings for different social groups.

Instead, I tried in vain to get a spokesperson from Nike, in nearby Beaverton, to address the class; I hoped that at least the company might send me a video allowing students to glean the corporate perspective. No luck. They sent me a PR packet of Phil Knight speeches, and their “Code of Conduct,” but stopped returning my phone calls requesting a speaker. I copied the Nike materials for students, and they read with special care the Nike Code of Conduct and did a “loophole search” — discovering, among other things, that Nike promises to abide by local minimum wage laws, but never promises to pay a living wage; they promise to obey “local environmental regulations” without acknowledging how inadequate these often are. Having raced themselves to the bottom in the transnational capital auction, students were especially alert to the frequent appearance of the term “local government regulations” in the Nike materials. Each mention might as well have carried a sticker reading “WEASEL WORDS.”

I reminded students of our soccer ball exercise, how we’d missed the humanity in the object until we read Bertolt Brecht’s poem. I asked them to write a “work poem” that captured some aspect of the human lives connected to the products we use everyday. They could draw on any situation, product, individual, or relationship we’d encountered in the unit. As prompts, I gave them other work poems that my students had produced over the years [for example, see Joel Gunz’s poem, “A Diamond,” included in my South Africa curriculum, Strangers in Their Own Country]. Students brainstormed ways they might complete the assignment: from the point of view of one of the objects produced, or that of one of the workers; a dialogue poem from the point of view of worker and owner, or worker and consumer (see “Two Women” in Rethinking Our Classrooms); a letter to one of the products, or to one of the owners (like Oregon-based Phil Knight, CEO of Nike). Cameron Robinson’s poem, below, expressed the essence of what I was driving at with the assignment.

Masks

Michael Jordan soars through the air,

on shoes of unpaid labor.A boy kicks a soccer ball,

the bloody hands are forgotten.An excited girl combs the hair of her Barbie,

an over-worked girl makes it.A child receives a teddy bear,

Made in China has no meaning.The words “hand made” are printed,

whose hands were used to make them?A six year old in America starts his first day of school,

A six year old in Pakistan starts his first day of work.They want us to see the ball,

not to see the millions of ball stitchers.The world is full of many masks,

the hard part is seeing beneath them.

As we read our pieces aloud (I wrote one, too), I asked students to record lines or images that they found particularly striking and to note themes that recurred. They also gave positive feedback to one another after each person read. Sandee wrote: “I liked the line in Maisha’s paper that said, ‘My life left me the day I stitched the first stitch…’ I like Antoinette’s paper because of the voice. It showed more than just pain, it also reflected a dream” — an ironic dream of a sweatshop worker who wants to flee her country for the “freedom” of the United States. Dirk had written a harshly worded piece from the point of view of a worker for a transnational company; it drew comments from just about everyone. Elizabeth appreciated it because “he used real language to express the feelings of the workers. As he put it, I doubt that the only thing going through their minds is ‘I hate this job.'” As a whole the writings were a lot angrier than they were hopeful; if I’d missed it in their pieces, this came across loud and clear in students’ “common themes” remarks. As Jessica wrote, “One of the things I noticed was that none of the [papers] had a solution to the situation they were writing about.” Maisha agreed: “Each paper only showed animosity…”

I expected the unit to generate anger, but I hoped to push beyond it. From the very beginning, I told students that it was not my intention merely to expose the world’s abuse and exploitation. A broader aim was to make a positive difference. For their final project, I wanted students to do something with their knowledge — I wanted to give them the opportunity to act on behalf of the invisible others whose lives are intertwined in so many ways with their own. I wasn’t trying to push a particular organization, or even a particular form of “action.” I wanted them simply to feel some social efficacy, to sense that no matter how overwhelming a global injustice, there’s always something to be done.

The assignment sheet [see the article: “Child Labor/Global Sweatshop: Making a Difference Project”] required students to take their learning “outside the walls of the classroom and into the real world.” They could write letters to Phil Knight, Michael Jordan, or President Clinton. They could write news articles or design presentations to other classes. I didn’t want them to urge a particular position if they didn’t feel comfortable with that kind of advocacy; so in a letter they might simply ask questions of an individual.

They responded with an explosion of creativity: three groups of students designed presentations for elementary school kids or for other classes at Franklin; one student wrote an article on child labor to submit to the Franklin Post, the school newspaper; four students wrote Phil Knight, two wrote Michael Jordan, and one each wrote the Disney Co., President Clinton, and local activist, Max White.

Jonathan Parker borrowed an idea from an editorial cartoon included in the “Justice. Do It NIKE!” reader. He found an old Nike shoe and painstakingly constructed a wooden house snuggled inside, complete with painted shingles and stairway. He accompanied it with a poem that reads in part:

There is a young girl

who lives in a shoe.

Phil Knight makes six million she makes just two.When Nike says “just do it”

she springs to her feet,

stringing her needle

and stitching their sneaks.

With Nike on the tongue,

The swoosh on the side,

the sole to the bottom,

she’s done for the night…When will it stop?

When will it end?

Must I, she says, toil for Nike again?

The “sculpture” and poem have been displayed in my classroom, and have sparked curiosity and discussion in other classes, but Jonathan hopes also to have it featured in the display case outside the school library.

Cameron, a multi-sport athlete, was inspired by a Los Angeles Times article by Lucille Renwick, “Teens’ Efforts Give Soccer Balls the Boot,” about Monroe High School students in L.A. who became incensed that all of their school’s soccer balls came from Pakistan, a child labor haven. The Monroe kids got the L.A. school board there to agree to a policy to purchase soccer balls only from countries that enforce a prohibition on child labor.

Cameron decided to do a little detective work of his own, and discovered that at the five Portland schools he checked, 60% of the soccer balls were made in Pakistan. He wrote a letter to the school district’s athletic director alerting him to his findings, describing conditions under which the balls are made, and asking him what he intended to do about it. Cameron enclosed copies of Sydney Schanberg’s “Six Cents an Hour” article, as well as the one describing the students’ organizing in Los Angeles — hinting further action if school officials didn’t rethink their purchasing policies.

One student, Daneeka, bristled at the assignment, and felt that regardless of what the project sheet said, I was actually forcing them to take a position. She boycotted the assignment and enlisted her mother to come in during parent conferences to support her complaint. Her mother talked with me, read the assignment sheet, and — to her daughter’s chagrin — told her to do the project. Daneeka and I held further negotiations and agreed that she could take her learning “outside the walls of the classroom” by “visiting” on-line chat rooms where she could discuss global sweatshop issues and describe these conversations in a paper. But after letting the assignment steep a bit longer, she found a more personal connection to the issues. Daneeka decided to write Nike about their use of child labor in Pakistan as described in the Schanberg article. “When I was first confronted with this assignment,” she wrote in her letter, “it really didn’t disturb me. But as I have thought about it for several weeks, child labor is a form of slavery. As a young black person, slavery is a disturbing issue, and to know that Nike could participate in slavery is even more disturbing.” Later in her letter, Daneeka acknowledges that she is a “kid” and wants to stay in fashion. “Even I will continue to wear your shoes, but will you gain a conscience?”

“Just Go With the Flow”

At the end of the global sweatshop unit, I added a brief curricular parenthesis on the role of advertising in U.S. society. Throughout the unit, I returned again and again to Cameron Robinson’s “masks” metaphor:

The world is full of many masks,

the hard part is seeing beneath them.

I’d received a wonderful video earlier in the year, “The Ad and the Ego,” that, among other things, examines the “masking” role of advertising — how ads hide the reality of where a product comes from and the environmental consequences of mass consumption. The video’s narrative is dense, but because of its subject matter, humor, and MTV-like format, students were able to follow its argument so long as I frequently stopped the VCR. At the end of part one, I asked students to comment on any of the quotes from the video and to write other thoughts they felt were relevant. One young woman I’ll call Marie, wrote in part: “I am actually tired of analyzing everything that goes on around me. I am tired of looking at things at a deeper level. I want to just go with the flow and relax.”

I’d like to think that Marie’s frustration grew from intellectual exhaustion, from my continually exhorting students to “think deep,” to look beneath the surface — in other words, from my academic rigor. But from speaking with her outside of class, my sense is that the truer cause of her weariness came from constantly seeing people around the world as victims, from Haiti to Pakistan to Nepal to China. By and large, the materials I was able to locate (and chose to use) too frequently presented people as stick figures, mere symbols of a relationship of domination and subordination between rich and poor countries. I couldn’t locate resources — letters, diary entries, short stories, etc. — that presented people’s work lives in the context of their families and societies. And I wasn’t able to show adequately how people in those societies struggle in big and little ways for better lives. The overall impression my students may have been left with was of the unit as an invitation to pity and help unfortunate others, rather than as an invitation to join with diverse groups and individuals in a global movement for social justice — a movement already underway.

Another wish-I’d-done-better, that may also be linked to Marie’s comment, is the tendency for a unit like this to drift toward good guys and bad guys. In my view, Nike is a “bad guy,” insofar as it reaps enormous profits as it pays workers wages that it knows full well cannot provide a decent standard of living. They’re shameless and they’re arrogant. As one top Nike executive in Vietnam told Portland’s Business Journal, “Sure we’re chasing cheap labor, but that’s business and that’s the way it’s going to be” — a comment that lends ominous meaning to the Nike slogan, “There is no finish line.” My students’ writing often angrily targeted billionaire Nike CEO Phil Knight and paired corporate luxury with Third World poverty. But corporations are players in an economic “game” with rules to maximize profits, and rewards and punishments for how well those rules are obeyed. I hoped that students would come to see the “bad guys” less as the individual players in the game than as the structure, profit imperatives, and ideological justifications of the game itself. Opening with the Transnational Capital Auction was a good start, but the unit didn’t consistently build on this essential systemic framework.

Finally, there is a current of self-righteousness in U.S. social discourse that insists that “we” have it good and “they” have it bad. A unit like this can settle too comfortably into that wrong-headed dichotomy and even reinforce it. Teaching about injustice and poverty “over there” in Third World countries may implicitly establish U.S. society as the standard of justice and affluence. There is poverty and exploitation of workers here, too. And both “we” and “they” are stratified based especially on race, class, and gender. “We” here benefit very unequally from today’s frantic pace of globalization. As well, there are elites in the Third World with lots more wealth and power than most people in this society. Over the year, my global studies curriculum attempted to confront these complexities of inequality. But it’s a crucial postscript that I want to emphasize as I edit my “race to the bottom” curriculum for future classes.

Enough doubt and self criticism. By and large, students worked hard, wrote with insight and empathy, and took action for justice — however small. They were poets, artists, essayists, political analysts, and teachers. And next time around, we’ll all do better.