The Heroes We Need Today: Teaching About the Radical Ida B. Wells

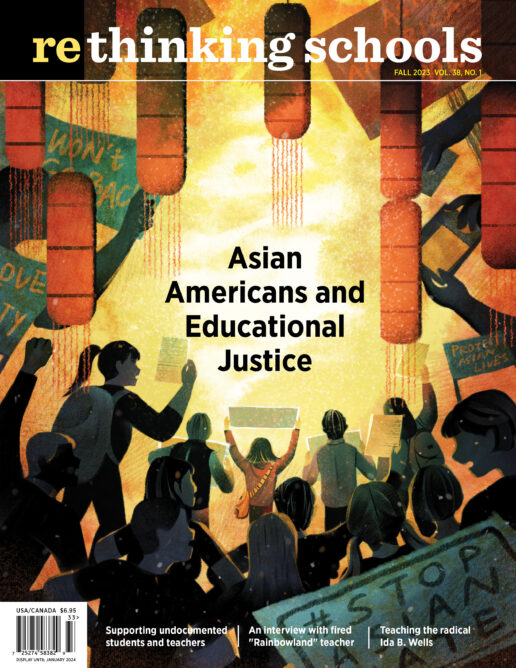

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

Greeting me at the door to the cafeteria where our first meetings of the school year took place was a buffet table of new and rebranded school mugs, stickers, tote bags, water bottles, pencils, and pens. I made my way through the line, picking through the new school swag and hardly concealing my excitement as the principal’s voice boomed through the loudspeaker: “Hello Guardians! Welcome back to Ida B. Wells-Barnett High School.”

In the wake of the uprising for racial justice following the murder of George Floyd, students and alumni succeeded in a decade-long struggle to change our school’s name, Woodrow Wilson High School. Our school became one of the more than 80 across the country to do so. In a letter announcing the change, the school’s renaming committee — made up of students, staff, and community members — wrote: “Remembered as one of the most lauded civil rights advocates of the 19th and 20th centuries, Wells-Barnett is an American hero. Ida B. Wells-Barnett will foster a lasting message of determination, valor, and tolerance among all students and staff.”

While there was the usual beginning of the school year mumble and grumble from veteran staff, the enthusiasm for our school’s new namesake, and the broader shift it represented, was palpable. Many made reference to Ida B. Wells’ legacy as we shared ideas for schoolwide policies, classroom expectations and possible schoolwide events. In fact, our school administrators consulted with Dan Duster, the great-grandson of Ida B. Wells, to revise our school’s core values: “At Ida B. we are: Wise with our choices, Excellent with our actions, Living with integrity, Leading with courage, and Speaking with passion.” When staff challenged schoolwide cell phone and attendance policies, many started or ended their critique with the question “And how do you think Ida B. Wells would address this problem?”

It was also during these rushed yet vital pre-service days that a small group of staff began to worry. We feared that Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s life message kept being reduced to nebulous concepts of determination, valor, tolerance, diversity, acceptance, and inclusion. At minimum, we felt that this framing erased the specific lessons from her life that are relevant today. At worst, we feared that this framing tamed her life of organizing and struggle for justice to make it more palatable for our largely white and wealthy school community. We especially found the emphasis on “tolerance” to be problematic. It is true that she endured decades of racist violence and sexist discrimination. But do we want students to embrace tolerance as a virtue above, say, resistance? We knew that Wells’ life taught much more.

* * *

In September 1919, a white mob attacked a Black sharecroppers union in Elaine, Arkansas, after they demanded higher prices for the cotton they grew and sold. Over the course of a week, white mobs killed hundreds of Black sharecroppers, their families, and their neighbors. After a sham trial, an all-white jury convicted 12 Black men of instigating violence and they were sentenced to death. One of the men wrote to Wells, asking her to conduct an investigation and tell the sharecroppers’ side of the story. The imprisoned men and their families believed that Wells might be able to exonerate them and hold the whites accountable for instigating the violence. Within a couple of weeks, Wells arrived in Elaine.

In her published investigation of the 1919 Elaine Massacre, Ida B. Wells wrote a scathing rebuttal to the local officials’ handling of the case, concluding that “twelve [Black men were] sentenced to death because they dared, in this democracy of ours, to ask relief from economic slavery.”

What made Ida B. Wells’ writing powerful then, as well as today, was her ability to expose the roots of racialized violence. In the case of the Elaine Massacre, she detailed landowners’ violence to prevent Black sharecroppers from securing higher prices for cotton and government officials’ support of white supremacist rule. Throughout her life, Wells used journalism and political activism to highlight the contradictions of the U.S. government’s rhetoric of “democracy” and collusion between powerful business interests and local political elites to maintain an unequal racial order. This commitment to tell the truth prompted an FBI agent to write that “[Wells] is considered by all of the intelligence officers as one of the most dangerous negro agitators.”

Inspired by this story and others that a handful of us researched, we wanted to create a curriculum to introduce students to her fuller, more radical life. We wanted students to see multiple examples of how she used the platforms she had — whether as a teacher, a journalist, an anti-lynching activist, or civil rights organizer — to expose the deeper truths behind racial inequality and the fight for a more just United States, where extrajudicial police violence is criminalized and ceases to exist. We wanted a curriculum that turned the light on truth about her life and legacy.

A group of us educators, including four social studies teachers, two language arts teachers, a librarian, and an instructional coach came up with an idea to host a weeklong camp to build this curriculum. Inspired by the curriculum camps facilitated by Linda Christensen through the Oregon Writing Project in partnership with Portland Public Schools, we petitioned our principal for an Ida B. Wells-specific curriculum camp. With his support, we met in the summer of 2022 to create a curriculum that could be taught schoolwide.

* * *

My contribution to this curriculum camp was a mixer activity. I developed a mixer activity in which each student takes on a role about a specific story or moment in her life. I modeled it after Bill Bigelow’s mixer activity about Rosa Parks. [See “The Rebellious Lives of Rosa Parks.”] I loved the way that mixer, through its rich stories, simultaneously introduces students to the broadness of her life and challenges the single story that most students receive about her diverse legacy of civil rights organizing.

In the Ida B. Wells mixer, students receive a first-person narrated story. Each role highlights the problem or issue Wells fought against as well as the action she took in response. For example, the role about Wells’ work as a co-founder of the NAACP:

In 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed. I was one of the founding members, along with Mary Church Terrell and W. E. B. Du Bois. A small group of white progressive activists in Illinois reached out to Black leaders, wishing to form an organization to protest racial violence and discrimination across the country. We saw this as an opportunity to re-energize our long demands for our full civil rights. At first, I had hope for what we could do as an interracial organization, but I quickly grew disillusioned. Most of the leaders were wealthy white men who wanted only to study the race problem. I thought this approach to justice was too passive. We knew all we needed to know about racial violence and segregation. What we needed was concrete action such as new laws.

Another example, taken from the role about Ida B. Wells’ Illinois suffrage work, begins:

I had long believed that winning the right to vote for women — what we called suffrage — was important. But I also believed it was important only if all women, Black and white, could vote. For years, white-led suffrage organizations excluded Black women. That’s why other Black women and I co-founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in 1913.

To start the role play, I distributed the roles to students, asking them to read them a few times, underlining important information, and listing three or four crucial facts “that you believe are the most important things for your classmates to know about Ida B. Wells.”

“Whoa! Ida B. Wells did that?!” was a refrain from multiple students as they read about Ida B. Wells fighting back against a train conductor who tried to remove her from a train car or her meetings with William McKinley and Woodrow Wilson to demand anti-lynching legislation.

Since every student in this mixer activity represents Ida B. Wells, I handed out nametags and asked students to write the word or phrase that is in bold font on their role on their nametag. That way students could have a visual reminder of the different snapshots into Ida B. Wells’ life they were interacting with. I invited students to “Place your nametag on your body when you’re finished reading so that I know when we’re ready for the next step.” The class became a living timeline, with students wearing nametags such as National Afro-American Council, Cairo, Illinois, and Scotland and England.

Next, I gave students questions to guide their conversations as they “mixed” around the room. “Your goal is to answer each question with information you learn from a different person. For example, ‘Find information that shows Ida B. Wells’ advocacy for women’s rights. What did she do?’”

After reading aloud each question with students, I reviewed our mixer ground rules; “These are real stories from moments in Ida B. Wells’ life. Please share them with care. No accents or stereotypes. Use your own voice. This is not a race — the point of this mixer is to learn from each story and stitch together a fuller understanding of Ida B. Wells’ life.”

To start the activity, I direct students to “partner up with a student seated a few desks away from you and introduce yourself. Say ‘I’m Ida B. Wells and I want to tell you about . . .’” It usually takes only a minute or two before students eagerly begin to share their roles.

In the mixer, students share stories about how Wells used journalism as a tool to fight against injustice. Take, for example, the role about the 1927 Mississippi Floods:

On April 21, 1927, the Mississippi River delta changed forever. After months and months of rain, the levees along the Mississippi River burst. Cities, towns, and farmland from St. Louis, to New Orleans flooded. . . . Weeks after the flood, I received letters from Black refugees about injustices in refugee camps set up by the Red Cross and U.S. government. The Black refugees described living in slavery-like conditions. They were forced to do labor for whites, not allowed to move freely in and out of camps, and often forced to sleep on wet ground in poorly made camps and alongside chickens, pigs, and cows. In contrast, whites were given housing in downtown apartments, given first pick of donated clothes, and provided much better quality food. Those of us at the Chicago Defender demanded that the U.S. government end these racist abuses. We published refugees’ firsthand accounts. We called on readers to write to President Coolidge and Secretary Hoover and demand justice. We refused to allow Black refugees’ plight go unnoticed when everyone from the Red Cross to the U.S. government and even other newspapers refused to tell the truth.

Students also meet Ida B. Wells as the innovative “data journalist,” among the first who used detailed records of lynchings to expose the truth behind state-sanctioned lynchings of Black men:

I am most well known for my journalism about lynchings. Between 1892 and 1900, I published four pamphlets: Southern Horrors, A Red Record, Lynch Law in Georgia, and Mob Rule in New Orleans. I included statistics of every publicly known lynching so that readers could see how far widespread the problem of lynching in the United States reached. Some called me a “data journalist,” since I was among the first to publish the raw data of what I was reporting about. These pamphlets also presented the Black perspective about lynchings to counter white propaganda. Too often, white reporters blamed lynching on Black people themselves. Instead, I humanized the lynching victims by conducting in-depth interviews with family, friends, and community members. My reporting showed that lynchings were not about seeking justice for crimes. Rather, they were used to terrorize, silence, and steal.

One of the joys of this activity is that students become “experts” about one part of Wells’ life that few knew about. This was the case of Marcos, who introduced himself by asking, “Hey, have you met Ida B. Wells while she worked at the Negro Fellowship League?”

An overlooked aspect of Ida B. Wells’ life is her work aiding Black migrants moving from the South to the North. As a former migrant herself who fled white-mob violence in Memphis, she made sure that new migrants to Chicago not only had food and shelter, but access to Black newspapers from across the country, legal aid, and a lively community center. The mixer includes a role about the Negro Fellowship League. I hoped that this role would alert students to how intertwined the fights for racial justice and migrant justice were during Wells’ life — as they are today.

Mixer roles from Ida B. Wells’ early life give students insight into her development as a radical. For example, one role highlights the importance of her parents in shaping her beliefs. Students shared these roles enthusiastically during the mixer. Sharing the story about the fight between Wells and a train conductor after she refused to sit in the segregated section of the train, Olivia shouted to another student, “And you know what, I bit him! I was not going to be moved without a fight!”

When most students had finished through question No. 8, I asked them to head back to their seats and individually write a response to four questions:

- What were things you learned about Ida B. Wells that you didn’t know before the mixer?

- What story or moment from Ida B. Wells’ life did you find most interesting, surprising, or inspiring?

- In 1918, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) described Ida B. Wells as one of the most “dangerous [Black] agitators.” What made Wells so dangerous from the perspective of the federal government’s leading law enforcement agency?

- What did you learn that confused you or that you’d like to learn more about?

To me, the best part of this mixer activity is the discussion after students write on these questions. I open the discussion: “So, what are some of the new things you learned about Ida B. Wells from the activity?” Students gravitate toward the sheer number of organizations — and movements — that Wells was part of.

Michelle kicked off one class discussion: “I knew she was a journalist, but I had no idea she was part of so many groups.” Angela added: “She seemed to do everything. Fought for Black rights alongside women’s suffrage. And she wrote for several newspapers. Is there anything she did not do?”

Ida B. Wells’ life offers a tapestry of civil rights activism at the turn of the 20th century. Luis, a student who admitted to me earlier in the year that history was “not his thing,” kicked off a conversation: “I think it is really cool just how brave Ida B. Wells was. She stood up for herself even when she knew the potential consequences. Like about not giving the buttons that protested the lynching of Black soldiers in Texas up [to the secret service agents].”

“Yeah,” added Annika, “She did what Rosa Parks did and refused to get off a train, but like 50 years earlier, and then sued and at first, won.”

Ben added, “And it wasn’t my role but she started a boycott after her friends were killed?”

Adam had the role about Ida B. Wells’ editorial advocating a Black-led boycott of businesses in Memphis: “She asked for people to move away from Memphis and that those who stayed would boycott.”

Jay shared that the story he loved most is how Wells walked in the front of her delegation during the women’s suffrage march, refusing to be racially segregated. Jordan captured the collective aha of the class: “So she fought for racial equality and gender equality, at the same time? Just like activists are fighting for today? What’s the word for that? Intersectionality?”

Students were surprised — and seemed eager to learn more — about stories of Wells’ early life — in particular, when she became the primary caretaker of her siblings after her parents died in a yellow fever epidemic. Logan wrote, “It’s amazing that she became a teacher when she was 16 to take care of her six siblings. She had to work for the week away from home, only came home for the weekends to wash and cook and clean. I’m 16 and I could never imagine doing that.”

This theme of personal sacrifice for the good of her community came up again and again. “She stood up for herself and her community, knowing the consequences and dangers of it. Like when she lost her job criticizing her school for the unequal treatment between Black and white schools. That’s really cool.”

I was impressed by the depth of reflection students brought to the question of what made Wells “one of the most dangerous [Black] agitators.” In one class, Whitney shared that they believed Wells was dangerous because “she wasn’t scared of telling the truth as a Black woman.” Olivia agreed: “I think what made Wells dangerous is that she was part of many groups who fought against inequality. The government did not want her to spark a revolution.”

* * *

Senya Scott, one of the eight student representatives on the school renaming committee, said that she hoped that the new namesake would inspire “A lot more . . . schoolwide dedication to [understanding] who Ida B. Wells was.” She added, “I want to see a lot more students dive into what representing her through this school means.” My hope is that this activity honors what Scott and the other students on the renaming committee wanted: In order to understand Ida B. Wells, it is important to consider her whole life’s work and legacy as a radical civil rights organizer and activist. Hers is a life of truth-telling activism, multiracial organizing, and class solidarity that teaches us that there is no sitting on the fence in the face of injustice — to do something, to not do nothing. Isn’t this what a school that is named after Wells is about? A place where students become intolerant of injustice. A place where students can learn and experience becoming activists for justice?

After the mixer activity, I asked students to write found poems in small groups using lines or information from their assigned roles or the roles of others. One group wrote about Wells’ determination to expose the truth about lynchings and her lifelong work to end state-sanctioned racialized violence:

Write that I was determined

My fight stopping for no one

One had better die fighting against

injustice then die like a dog or a rat in a trap

Write that I was strong-willed

Boycotted Memphis

I dreamt of anti-lynching legislation to pass in the early 1900s

I waited more than a century

My dream came true

But how long did it take?

Another group used their found poem to hone in on Wells’ multiracial suffrage organizing:

Write that I marched for suffrage

Not just for white, but for all

They told us to remain behind

But I found my way to the front

The others followed

And-we-were-connected

Not by differences

But by humanity

“I’ll march with you or not at all”

When we take action for justice — through writing, speaking, organizing — it connects us with others who are fighting for more just worlds. And the struggle for truth and justice is how we stave off the cynicism and despair that feeds off our crushed hopes for a better tomorrow.

Aren’t these the messages about Ida B. Wells that students need now?

For teaching materials related to this article, click below:

Ida B. Wells Mixer Roles and Questions