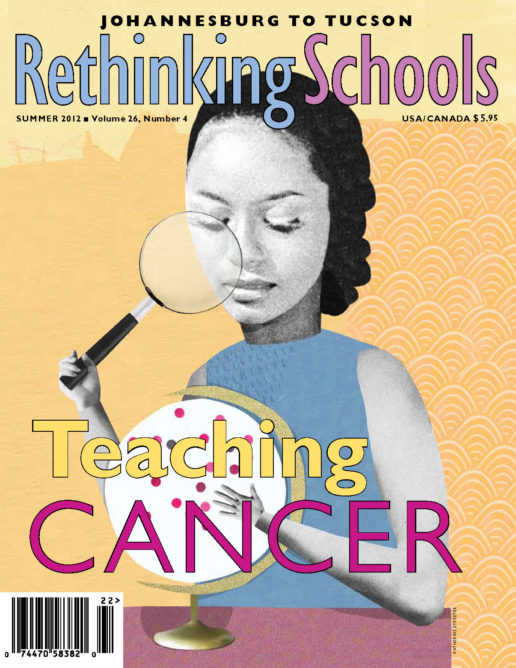

The Danger of a Single Story

Writing essays about our lives

Illustrator: Jordin Isip

On the first day of spring break, a number of Jefferson students chose to attend a rally for Trayvon Martin. Wearing their hoodies, they listened to speakers connect the killings of young black men over the years—from Mississippi to Florida to our home in Portland, Oregon. Two Jefferson students, Jalean Webb and Kelsie Turner, took the microphone and talked about feeling endangered. Kelsie brought us to tears when he said, “I wore a Ninja Turtle hoodie today because I wish I could go back to a day in time when I didn’t have to worry about these problems, to a time when I didn’t have to worry about me being an almost grown man and people feeling like they have the right to shoot me.”

Black male students are endangered. As a high school language arts teacher who has taught in a predominantly African American school, I’ve witnessed the suspensions, expulsions, and overrepresentation of black males in special education classes for more than 30 years. In The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander tells readers that the number of African Americans in prison, jail, or on probation today is greater than the number of African Americans enslaved in 1850; in 2004, there were more African American men who could not vote because of felony disenfranchisement laws than in 1870, when black people were explicitly denied the right to vote based on race.

The vulnerability of black males came home for me some years ago when I co-taught a handful of young, mostly African American male 9th graders. Their ability to get crossways with teachers and security guards troubled me. Their stories of stops by police officers weren’t new, but in these boys-turning-into-men, I witnessed the intersection between children surprised by the racism that their brown bodies brought them, like the unwanted attraction of yellow jackets to a barbecue, and the tough-boy masks they created to survive. Like Kelsie, they still wore their versions of Ninja Turtle hoodies, but the world saw them as dangerous.

As I listened to their stories, I thought about the Daniel Beaty poem that laments the “lost brilliance of the black men who crowd prison cells,” and I thought about my moral obligation to tap into this injustice, this birthplace of anger and rage, to expose it and validate students’ experiences. But if I unleashed this rage and pain, I knew I had the parallel moral obligation to teach students how to navigate a society that discriminates against them and to teach them how others have dealt with these injustices. So I designed curriculum to address the needs of these black youth, and also the needs of all my students who feel singled out because of a defining feature that turns them into a target.

Creating assignments that do the double duty of teaching students to read and write while also examining the ways race and class function in our society is absolutely fundamental today. As I write this article—to discuss an assignment that pushes students to analyze how their lives have been shaped by the “single stories” told about them—I am also writing to talk back to the galloping standardization that expects all students to reach higher standards through uniform readings that either bore them or have little relevance in their lives. When students are pulled from police cars, followed in stores, suspended for refusing to obey ridiculous orders, our job as teachers must be to produce a curriculum that demonstrates that they are not alone and not crazy. At the same time, we must give them tools to dismantle those mistaken assumptions.

‘Unwieldy Influences’

“The Danger of a Single Story,” the title of this reading and writing assignment, comes from a talk by Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie that is part of the TED series. “The single story creates stereotypes,” Adichie says, “and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” I have adapted and recreated the lesson in a number of classroom situations over the years as I’ve come to appreciate the vulnerability of all teenagers who have come to bear what Brent Staples calls the “unwieldy inheritances” of stereotypes. Adichie’s and Staples’ work become models for students learning to write a personal essay, using vignettes (small stories) from their lives as evidence.

This year, as an introduction to the assignment, I tell stories about how people have made assumptions about me because I taught at predominantly black Jefferson High School. During the almost three decades I taught at Jefferson, where I now return to co-teach a junior language arts class with Dianne Leahy, I frequently found myself defending the school. When I won teaching awards, folks would come up to me and say, “Now maybe you can get a job at a good school.” When I held after-school workshops at Jefferson, I was warned that no one would come because they didn’t want to be in the neighborhood after dark.

I read my students the beginning of a vignette essay that I wrote on the topic:

“I don’t understand how you could walk into that building day after day for 22 years,” the older woman standing at the copier told me. “I have to go in there once a week, and I fear for my life every time I walk up those stairs. All of those black boys with their hoodlum clothes—sweatshirt hoods pulled up over their heads, baggy pants—I’m afraid they’re going to knock me down the steps and steal my purse.”

I choose the Jefferson story because our school is a joy and burden that we share. Jefferson is perceived by many—some newspapers, some neighbors, some students and/or teachers from other schools—to be a failing school, and a dangerous one. Students know the litany of supposed “sins” of Jefferson: Students are not smart, girls get pregnant early, students fight, bathrooms aren’t safe, students bring weapons to school, kids in gangs go to Jefferson, teachers are weak.

‘Just Walk on By’

I start the lesson by reading Brent Staples’ powerful essay, “Just Walk on By: Black Men and Public Spaces.” In this article, originally published in Ms. magazine in 1986, Staples discusses “the unwieldy inheritance” he came into—“the ability to alter public space in ugly ways”—with his presence as an African American man. It both saddens and enrages me that in the nearly three decades since its first publication, Staples’ story is still relevant. Throughout the essay, he shares vignettes of times when he was identified as a threat:

The fearsomeness mistakenly attributed to me in public places often has a perilous flavor. The most frightening of these confusions occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when I worked as a journalist in Chicago. One day, rushing into the office of a magazine I was writing for with a deadline story in hand, I was mistaken for a burglar. The office manager called security and, with an ad hoc posse, pursued me through the labyrinthine halls, nearly to my editor’s door. I had no way of proving who I was.

He discusses the shame and humiliation—as well as the rage—that come from being designated as a potential criminal. There is “no solace against the kind of alienation that comes of being ever the suspect, a fearsome entity with whom pedestrians avoid making eye contact.”

Staples’ essay is a writing teacher’s dream. It provides a clear model of how to write a personal essay, and it illuminates a compelling topic with which many students identify. That said, it is not an easy read for struggling students. Before we begin, I ask students to keep track of Staples’ vignettes in the margins of the essay—women moving away from him clutching purses to their chests “bandolier style,” a jewelry store incident in which the proprietor brought out a Doberman pinscher “straining at the end of a leash” when he entered the store. We take frequent breaks to talk about his examples and his language and the structure of the essay. Students share their own experiences along the way—times strangers’ car door locks clicked down when they walked past, times they were followed in stores, times when white women hurried away from them, times when teachers made assumptions about their ability or intelligence based on their skin color. We read Staples’ essay like we are eating a gourmet meal, pausing to savor morsels of language and story along the way.

Once we finish reading Staples’ piece, we watch Adichie’s talk. Adichie, like Staples, develops her theme, “The Danger of a Single Story,” through a series of vignettes about times when she has had a “single story” told about her because she is from Africa. She is charming as she regales her audience about how people sometimes fail to distinguish her country—Nigeria—from the continent of Africa, how her college roommate wanted to hear her “tribal music.” In an opening vignette, she describes how her British colonial education taught her through its book choices that writers were white, drank ginger beer, and talked about the weather, so when she started writing stories in elementary school, her characters were white, drank ginger beer, and talked about the weather. Through these small stories, she shows how colonial education made African lives invisible: Their art, their language, their literature were not seen as worthy of study. This is a story that, unfortunately, resonates with many U.S. students, who also experience the literary canon as white.

Adichie also discusses times when she has fallen into the “single story” rut as well. Her language, like Staples’, is beautiful and poetic. Much to my students’ chagrin, I stop the video along the way to discuss each story. I ask students to record how Adichie develops evidence in her vignettes to support her ideas about the danger of a single story.

Making Lists, Telling Stories

Once students have the big picture of using personal stories to create an essay about the danger of a single story, we brainstorm the potential single stories that people have created about us. My list includes: Jefferson teacher, white teacher, person over a certain age, person over a certain weight, person who lives in a gentrified neighborhood. When I create my list, I attempt to make it broad enough so that all students can find a way into the essay: Race, age, weight, class, neighborhood, school are categories that allow most students to find traction.

This year students wrote about being black males, black females, Latinos and Latinas, students at Jefferson, poor, male dancers, boys who sag; one young woman wrote about the danger of her hair.

After students create lists, I say, “Do you have stories that support your topic? For example, if I’m writing about how I was disrespected because I taught at Jefferson, I need to give examples of times when that happened. What stories do you have?” We read a model that Deion Guice, a Jefferson student, wrote when he was in the 9th grade. (As a side note, we discuss the “n-word.” I developed an essay lesson on this based on the NAACP’s burial of the “n-word” and Michael Eric Dyson’s discussion and debates on the topic several years ago. Our class policy is that we do not say the “n-word” in class.) Deion’s model is more accessible than either Staples’ or Adichie’s, and it also occurs in the Jefferson neighborhood. Deion begins his essay with a series of questions, then moves into his first vignette:

Why must people make me feel like I’m a criminal? Is it because I’m six feet two inches tall and weigh 215 pounds? Or is it because I have a beard and look like I’m older then I am? Is it because I’m black?

During the summer of my 12th year, I walked to a corner store by my house. I went to go get something to drink. When I walked into the store, the clerk gave me a look as if he looked into the future and saw me stealing something. I went to the beverage section to get a Coke and when I turned around, I bumped into a white man in his late 50s. He turned around and got one good look at me then yelled out, “I HATE YOU NIGGERS” and poured his drink on my all-white shirt. I was surprised that, even though I was the one who was disrespected, the clerk and the bystanders in the store gave me disgusted looks. The clerk yelled at me, “I am going call the cops if you don’t don’t leave this store.” So I ran all the way home and cried when I got there (I never told anyone that, though).

In another vignette, Deion writes about an incident with the police:

Friday: Game night, and we’d just won our basketball game. We were excited and happy. After shooting hoops in the driveway, we decided to play crackhead race. In this game, we spin around and around until we’re totally dizzy, then we race to see who can get to the corner first.

When we are getting to the end of the block, the cops pulled up and I’m thinking to myself, this is gonna be trouble. When a cop, a white cop at that, sees two black teenagers wobbling down the street, that’s a bad start from the get-go.

The cops stepped out of the car, walked up to us, and asked if we knew what time it was.

I said, “Yes, it’s 11:45.” I was reaching into my pocket to get my ID. Without hesitation, the cop pulls out his gun and puts it to my head. At this point, I don’t know what to do. I’m just frozen. I’m speechless.

My friends are yelling at the cop, saying, “What are you doing?” The cop cusses at them. Tears of anger come out of my eyes and burn my face. . . .

After the cop leaves, I stomp down the street armed with my anger, and as I turn the corner, I bumped into one of John’s neighbors. When I look at him, I picture the cop, and I go off. I punched him two times until he drops. Johnny came and got me off him. I didn’t sleep that night.

Deion’s essay provokes testimonies. Several African American juniors—Terry, Daniel, and Kurt—tell parallel stories to Deion’s. Latina/os—Marcos, Maria, and Juanita—bring in slightly different versions. Their stories are more about “Are you legal?” and “Do you speak English?” and “When will you get pregnant and drop out?” The classroom erupts with tales of being followed and comments about their hair or weight or gang affiliation—and, this year, many stories about being disrespected as a Jeffersonian.

I find it is important to pause at this point in the assignment because, as I mentioned earlier, we are not only learning to write essays, we are exploring how students feel disrespected and discriminated against because of their identity—topics that are not always discussed in school.

Through the conversation about these painful accounts, I want to cement the idea that these accusations, these “unwieldy inheritances,” are not only wrong, but also dangerous misconceptions that we need to counter. The act of raising the issues and talking about them helps take the sting out of the wounds: “Oh, how great that you are still in school. Most Mexican girls drop out and get pregnant by the time they are your age.” We answer, “How dare someone say that to you?”

Once we’ve raised the stories and discussed them, I ask students to write one vignette, one of their stories. We look back at the models—Brent Staples’ and Deion Guice’s. “What do you notice about the way they wrote this vignette?” I ask. In the language of the Oregon Writing Project, we call this “raising the bones” of the model. When students look at model essays, I want them to recognize how the writing is structured, so when they have a new essay, narrative, or poem to write, their understanding of the “bones” or skeleton of the model piece will help them enter their own. In this case, students notice that the vignettes are short—just a paragraph; that they sometimes have the elements of a narrative—dialogue, characters, setting; that they make their point quickly. They also notice that the first paragraph, the introduction, frames the rest of the vignettes, setting up the idea for the essay. If they don’t notice, I nudge them to pay attention to the transitions between the paragraphs, how the writer weaves the separate stories into one essay. For example, in the excerpt from Brent Staples, his transition ties back to his thesis statement about black men in public places, and moves the reader into the time and place of the vignette he is preparing to share:

The fearsomeness mistakenly attributed to me in public places often has a perilous flavor. The most frightening of these confusions occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when I worked as a journalist in Chicago.

Modeling: Sharing the First Vignette

Because I believe in the power of students’ writing to provide great models for their classmates, I try to end our first writing session with a brief reading from those who caught some fire on their first draft. As students share their first vignettes, their pieces help the stuck student, the couldn’t-find-a-topic student, the I-don’t-know-where-to-start student out of their helpless state better than my talks. For example, Desi Barksdale wrote about the single story of Jefferson:

I looked out the window at Alberta Street passing by. I watched the barbershops blur with the record stores, the houses with the boarded-up windows and graffiti mix with the organic produce markets.

I was so deep in thought that I didn’t notice a boy with dark curly hair and small brown eyes slide into the seat in front of me, I didn’t notice when he turned around and stared at me, I almost didn’t even notice when he started talking.

“What?” I took the headphone out of my left ear and frowned at him.

He laughed, “I said, what’s your name, cutie?”

“Oh. Desi.”

“That’s a nice name, Desi. You go to school around here?”

I took the other headphone out of my ear. “Yeah, Jefferson.”

He let out a whistle, real low and long. “Jefferson,” he repeated. Then he laughed. “What’s a white girl like you doing going to a n***** school like Jefferson?”

“Excuse me?”

I couldn’t believe he just said that! I was so surprised that someone could have the audacity to say something so racist, so stereotypical, so wrong. I couldn’t even imagine thinking that narrow-mindedly, and here this boy was spitting out that garbage about my school.

Melissa Ferguson wrote about the stereotypes of young, black women—from being in gangs, to getting pregnant early, to leading tragic lives, to being illiterate. Her vignette sets the stage:

I had just got out of a hard day of practice and my mom called and said, “You have to catch the bus home because I will not be able to get there in time from work.” So I walked down to the bus stop pissed off, sore, cold, tired and hungry. Sitting at the bus stop for almost 15 minutes, a woman that is there every time that I’m there sits next to me and we begin to small talk.

“It’s raining hard out tonight, huh?”

“Yeah, and it’s really cold too,” I say.

“Yes it is. Do you go to the school down the street from here?” she asks.

“Yes, I just got out of practice,” I say.

“Oh, really, what sport do you play?”

“I run track.”

“Oh that’s good, you look like you are very athletic and can run really fast.”

“Yeah, I love it, it helps me release my stress.”

“That’s good. Track was always my favorite sport, but let me ask you this: is Jeff a gang-related school?” “NOOOOOOOO, why?”

“Oh well, it’s just every time I see you, you got on blue, and isn’t blue a gang color?”

“Yes, it is!”

“Are you a gang member?”

“No, I just love the color blue. I get good grades in school and am doing a sport and also working. I have no time to gangbang and be in the streets. I’ve seen too many of the people that were near and dear to me lose their life to a bullet from gangbanging and that’s not how I am deciding to live my life, always in fear of me and my family and what they will do to us, due to the fact that I bang a certain hood that they don’t like.”

She nods and looks out to the street.

“Well, here is the bus; you’re a smart kid, keep your head up,” she says. I walk on the bus after her with a feeling that I proved once again that someone who looks at me thinks because I’m black and young that I am a good-for-nothing troublemaker.

In this first share, typically during the last 10 minutes of a 90-minute class, I want students to get the feel of writing vignettes—from the use of dialogue and setting to the power of a short story to evoke the larger idea of what it means to be young and black, or white and poor, or a student who chose to come to Jefferson. But I also use these first-draft readings to point out elements that I want students to put in their essays. At the end of Melissa’s vignette, for example, she sums up her experience by stating how she felt as a result of this exchange at the bus stop, “I proved once again that someone who looks at me thinks because I’m black and young that I am a good-for-nothing troublemaker.” I tell students this is one way to land the ending of the vignette—to state how the incident makes you feel.

Writing and Revising Vignettes

Over the course of a two-week period, students wrote, typed, shared, and revised their essays. Students’ vignettes became mentor texts for the students who came late, missed class, or needed another nudge in order to move forward. If a student was stuck on a part, Dianne and I sent them to talk with a student who knew how to navigate the stories, the opening, the transition, or the conclusion.

Let me confess: This is a messy process. Our students exhibit diverse skill levels. A few have already passed college-level writing courses taught at the community college across the street, others are English language learners or have learning disabilities, so the timeline stretches, as do our expectations. Dianne and I conference with students who have strong essay writing skills about sentence structure, using stronger verbs, or refining their vignettes. For struggling students, we focus on the big idea of essay: introduction, evidence through story, and conclusion. Everyone revises. For all students, we discuss their stories, talk through the issues that erupt from their vignettes. This is how untracked classes work.

As the director of the Oregon Writing Project, I find that teachers sometimes initially come to our writing institutes expecting that we know how to fix students’ writing problems. We do. And we don’t. Writing takes time. Students don’t get it all at once. There’s no miracle except this: Give students meaningful assignments that they want to write and revise. When I interviewed a group of Latina/o and African American juniors after one of our first essays, I said, “I noticed at some point you stopped doing this because it was an assignment, and you became passionate about writing the essay.” Their answer: We got to write about issues that were real in our lives, and someone listened and cared.

So What?

Ultimately, I use Staples’ essay—and the vignette essay assignment—not only because of its relevance, but because Staples provides insights into how he has dealt with his “unwieldy inheritance”:

Over the years, I learned to smother the rage I felt at so often being taken for a criminal. Not to do so would surely have led to madness. I now take precautions to make myself less threatening. I move about with care, particularly late in the evening. I give a wide berth to nervous people on subway platforms during the wee hours, particularly when I have exchanged business clothes for jeans. If I happen to be entering a building behind some people who appear skittish, I may walk by, letting them clear the lobby before I return, so as not to seem to be following them. I have been calm and extremely congenial on those rare occasions when I’ve been pulled over by the police.

And on late-evening constitutionals I employ what has proved to be an excellent tension-reducing measure: I whistle melodies from Beethoven and Vivaldi and the more popular classical composers. Even steely New Yorkers hunching toward nighttime destinations seem to relax, and occasionally they even join in the tune. Virtually everybody seems to sense that a mugger wouldn’t be warbling bright, sunny selections from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. It is my equivalent of the cowbell that hikers wear when they know they are in bear country.

I abhor the fact that my students must create “precautions” to keep themselves safe, but I know the alternative, as Trayvon Martin’s murder sadly exemplified. So far, no one has started whistling Vivaldi in class, but over the course of the year, students have learned both the danger of a single story that others have created about them, and the value of reclaiming their own identity.

As Troy states at the end of his essay:

As a black male in America, I never let my guard down to racism. Because if I do, it will smack me right in the face. We are easily stereotyped and people automatically think we are up to no good. One thing I will never do is try to flip out on people because that would only prove them right about us. When encountering racism, I just move on with my life, so I will stop being affected by other people’s portrayals of me.

Of course, this writing assignment is not enough to save our children. Not wearing hoodies isn’t enough, not walking in neighborhoods where their presence is seen as a threat isn’t enough. Even ending the Stand Your Ground law in Florida is not enough. As schoolteachers, we must use the tools we have: stories and history to teach students that the only way change happens is when people come together and act. And some of them might be wearing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle hoodies.