The Constant Testing of Black Brilliance

Illustrator: Ebony Flowers

At the Black Teacher Project, an Oakland-based organization designed to uplift, develop, and sustain Black teachers across the nation, we often ask ourselves: “Why do you teach?”

I am fueled, in part, by the memory of my 6th-grade teacher who refused to put me in the honors history class.

I received an A in her class, and all children with an A were supposed to advance to honors. When I asked my teacher about it, she pointed to my book bag — overflowing with papers and textbooks — and told me, “You’re too disorganized for an honors class.”

I certainly was a messy kid, but I knew that was an excuse, and it was humiliating to have to prove that in spite of the way my backpack looked, I was smart and worthy of advancement. After a couple days of asking her to put me in the honors class, she eventually approved my appeal, but it was conditional: “Fine, but you’ll have to learn to be neat.”

The next day, I went to the honors class. I was the only Black student. The other children of color had been tracked into the “inclusive class” that the honors students referred to as the “dumb” class. That class was composed of Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, international children of color, poor white kids, and the few other Black kids who went to my school. Whenever I passed their classroom, they were either watching a movie or giving the teacher hell.

This experience was one of many that taught me an important lesson about white supremacy: It is a hydra. I would always have to prove myself and pass a test. And after each test, there is another test. Testing of my intellectual capacity, of my authentic Blackness, of how well I follow rules and norms I don’t even know are being arbitrarily applied to me. If I wanted to survive as a Black student, it was wise to come with a sharpened No. 2 pencil in my pocket. At any moment I could be tested and asked to perform.

My current work with Black educators and students has allowed me to reconnect with that young girl looking for a safe learning community that did not subscribe to racist stereotypes. At the Black Teacher Project, we have all been impacted by the subtle and overt racism in our schools — and in our own educational histories. We have witnessed how this exclusion happens to us, students, staff, faculty, and parents. Though we gather as a community to creatively address these challenges, we do not deny that navigating these structures is tiresome.

When you’re constantly trying to rework yourself around other people’s bias, it is important to find community where your humanity is not up for negotiation or debate — or where your community is not defined by a test.

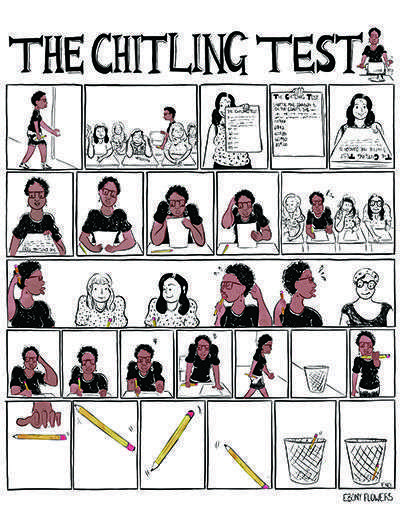

The Chitling Test

The constant testing during my educational journey didn’t stop when I graduated from high school, and one of the most profoundly racist experiences with testing I had was when I was a student teacher.

The teacher education program I was in prided itself on training educators committed to social justice and equity in and outside the classroom. Yet, I experienced much interpersonal and institutional racism, and even there I was expected to take out my No. 2 pencil and take a test. This time it was the Chitling Test.

Taking the test was supposed to help us understand the culture and lived realities of our students, specifically Black students. The Chitling Test, also known as the Dove Counterbalance General Intelligence Test, was developed by Adrian Dove in 1968. Dove, a Black sociologist, designed the test to expose the implicit bias in standardized IQ tests, which favored the experiences of white middle-class students. Dove’s response was to design a test that favored the experiences of Black students — and primarily Black students from historically exploited neighborhoods.

Without explaining anything about the history of the test, or the context in which the professor was giving it to us, she instructed us to take the Chitling Test. I scratched my head as I looked at the questions:

Hattie Mae Johnson is on the County. She has four children and her husband is now in jail for non-support, as he was unemployed and was not able to give her any money. Her welfare check is now $286 per month. Last night she went out with the highest player in town. If she got pregnant, then nine months from now how much more will her welfare check be? (a) $80, (b) $2, (c) $35, (d) $150, (e) $100.

Reading through the questions, I was torn between rage and confusion: Who’s to say all Black children experience this? And even if they do, how is this helping anything?

The Hattie Mae question reminded me of President Reagan’s 1986 speech on “welfare queens” and the “permanent culture of poverty” in Black communities. He said there were too many handouts — too many single mothers cheating the system. I felt Dove’s test supported the dominant narrative, pathologizing a people’s history and suffering. I could not see how taking a test — especially this test — would give us the proper tools to teach and understand Black culture, or any culture. Perhaps the test served a particular role in the late 1960s in opening the lid on biased thinking, but there have been considerable changes in appropriately addressing the particular struggles of Black people — and in design and bias thinking — in the following 50 years. Where was the nuance acknowledging the complexity of Black culture and life?

My sister, who was visiting from New York City where she was working as a substitute and after-school teacher, sat in on the class with me. She raised her hand in befuddlement and asked the professor, “How does this test teach us about understanding the children we teach?”

The professor responded that it was our duty to understand the backgrounds of our students and asserted that the test had been developed by a Black male sociologist who had conducted extensive research on this topic. I suppose since a Black man had engineered the test it carried the gold seal of anti-racist approval. Which meant the white professor had carte blanche to tout the test as a culturally responsive tool in understanding Blackness.

The question my sister asked could have led to inquiry and unpacking ideas about experiences that run counter to dominant worldviews. But that didn’t happen. I couldn’t express the thoughts running through my head but I remember thinking: Why do you hate me and my people? Why are you so out of touch? Please, stay away from Black children! Don’t hurt them anymore. Don’t hurt me anymore.

We were encouraged to take the test and I did, wondering how knowing what a “handkerchief head” proved that I was an expert in the Black experience. I don’t know whether the test achieved its goal for the other students in our class. But for me, a Black woman in a predominantly white teacher training program, the test was dehumanizing.

Yet again, Blackness was being tested, and this time it was taking a toll on my development as a teacher. The program triggered the anxiety I felt as a young student fighting her way into the honors class. I froze. I did not have the language to name or validate the marginalization I was encountering, or the tools to move myself from a place of victimhood to empowerment.

Looking back now, I can see that my teaching preparation program was not a safe place for me to learn and thrive as an aspiring teacher. There was no point trying to prove myself. These predominantly white educators, and the few people of color there, had personal work to do around their perceptions on Black identity and humanity. As adult learners, we have our difficulties understanding each other across difference, and locating our own cultural and equity perspectives. As a cohort, we were divided and distrustful of each other. Little priority was given to build learning partnerships and trust within our educational community.

As aspiring teachers at a critical juncture in our learning path, we were what former teacher and education consultant Zaretta Hammond, author of Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain, calls dependent learners. Dependent does not mean there’s a deficit within the learner, it just means that the student has not moved into a place of becoming an independent learner, prepared to pursue knowledge without the continuous support and approval of a teacher. We constantly looked to the professor in the room to see if we had the “right” answers and analysis when it came to testing our knowledge. We weren’t engaged in our own productive struggle to expand and investigate our practice. We needed teachers who could acknowledge and honor difference, locate and connect our sociopolitical narratives, and push us to build our brain power for the students we would one day teach.

Black Brilliance

The Chitling Test — though a loaded way to introduce a subject — could have been an opportunity to learn about U.S. history and its bearing on the Black experience. Chitlins were the scraps white folks gave to Black people to eat. It was the slave masters who saw fit to give Black people their hand-me-downs and rotten food.

If we want to know anything about chitlins, then we must investigate the primary relationship that birthed their existence — the relationship between the slave master and the slave. There was no choice but for Black people to nourish themselves off of white supremacy’s limited menu. In such gross conditions, Black folks were creative enough to make chitlins taste all right; they were able to take the scraps of the master and make jambalaya, gumbo, you name it. Black brilliance did that.

Black people have been creating pathways to free ourselves from the onslaught of death and poverty for centuries. If anything, we are a people of surviving and thriving, using the best of our minds and spirits to recreate ourselves in some of the most trying of circumstances. We are the very definition of the rose growing from concrete or the lotus flower shining in muddy water. Nothing short of validation and affirmation is in order! I can only wonder how my first years as an educator would have been different if my teacher training program empowered all of us to acknowledge our own narratives and history. We could have used our self-reflection to build sincere bonds amongst ourselves and students.

As Black teachers teaching Black children, we may not always identify with the experiences of our students. That’s when students become our greatest teachers. That’s when we humble ourselves and investigate if our practice is truly responsive, or if we are unconsciously testing our students and hoping they will engage in a way that brings us temporary comfort instead of mutual growth. Working through that discomfort starts with the deconstruction of our own cultural norms and personal histories.

If it weren’t for the writings of Michele Foster, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Sonia Nieto, Audre Lorde, and bell hooks, I would not have survived my teaching program. Their writing gave me faith to continue on my educational path, even when it hurt, and even when I failed.

I was tired of reading liberal white teachers giving me expertise on how they taught Black students and students of color. I was done with the single story of the white savior who understands everything there is to know about everyone but himself! Behind my teaching program’s back, I read Monique Redeaux’s essay in City Kids, City Schools. She fiercely challenges the outsider-looking-in complex: “I am attentive to the way my students are described, portrayed, perceived. Because I teach ‘these children.’ And I am one of ‘these children.’ I do not locate myself out of my practice.”

When we look at the low percentage of Black teachers in the field, it is obvious that many school systems struggle with seeing Black K-12 teachers and students as having brilliance and knowledge to share. If we were to uncover all the stories of how Black teachers and students have been pushed out of the classroom, or have had to give over the very best of themselves to stay in the classroom, it would blow us out of the water. There is a litany of horror stories about what it means to teach and learn while Black. Frankly, how Black people and people of color weather such aggression and still wake up with the will to teach exemplifies how brave we are.

A Black Teacher-Led Affinity Space

Working to provide critical professional development experiences in the Black Teacher Project has been a transformative experience. It has been a culturally responsive space where I and other Black teachers can focus on teaching with excellence without having to navigate microaggressions while having to prove that we are both culture keepers and knowledge bearers.

I have had the opportunity to make right the trauma I experienced as a student teacher, and it has made me believe it is possible for Black people to find ways to sustain themselves and thrive in their school contexts — but we have to implement the systems and structures to make that happen.

I have heard participants say, “It’s nice to be seen for my leadership capacities! Usually people just want me to be the disciplinarian of all the Black kids,” or state, “It’s nice to be around other Black teachers. I don’t feel isolated anymore.” Our need as Black teachers to learn from each other in affinity is a right and responsibility. An all-Black learning environment does not mean the problem is solved, but it does mean we acknowledge the necessity for us to gather together.

Preparing young people for a world positioned to be unforgiving is not something to be taken lightly. Educational equity and social justice are matters of life or death. In racial affinity, we can celebrate the ways we are doing the work to save our own lives. We can celebrate the multiplicity of Blackness. We can learn there is nothing to prove, no test to take, who we are is just enough. Finally, we can focus on the work we came here to do: Teaching with excellence.