The Chilling Effects of So-Called Critical Race Theory Bans

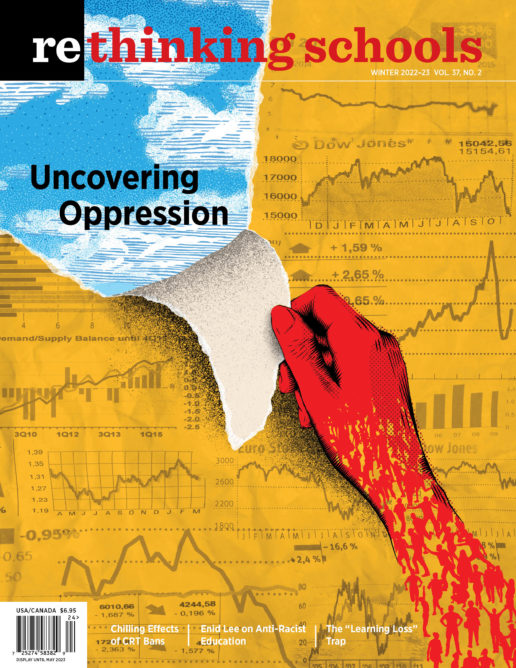

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

“It’s a slap in the face.”

That’s how one teacher described the “Prohibited Concepts in Instruction” law passed by the Tennessee legislature in spring 2021. The law was one of a series of laws commonly referred to as critical race theory bans, which were passed in 16 states with Republican-led legislatures as of the end of the 2021–2022 legislative session. Tennessee’s version prohibited 11 specific concepts, including “This state or the United States is fundamentally or irredeemably racist or sexist.” Such laws, many have argued, are intentionally designed to prevent K–12 teachers and students from engaging in critical conversations about race, gender, and oppression.

Ironically, so-called critical race theory bans actually exemplify the racist policy structure that critical race theory attempts to explain. Critical race theory explains in part how the law functions to uphold racial inequality. Because prohibited concepts legislation limits how educators teach about racism, these laws themselves maintain the racial status quo, the very phenomenon critical race theory describes (Hamilton, 2021).

As teacher educators and researchers in Memphis, Tennessee, we talked with practicing and prospective teachers and found that they, like us, were staunchly opposed to this new legislation. We are a multiracial team (two Black — African American and Haitian American — and two white researchers) who worked together in a justice-oriented teacher education program. Many of our initial conversations turned quickly toward concerns about effects of the law on everyday teaching and learning. What would it look like to teach about slavery or the Civil Rights Movement? How would teachers guide students in understanding the fundamental role of racism and other forms of oppression in shaping current events?

To better understand how this law might affect teaching and learning toward justice, we engaged 31 practicing and prospective teachers in focus group conversations about the legislation. Twenty-three of our participants identified as female. Of the 31 participants, 19 identified as white, nine as Black/African American, two as white and Latinx, and one as Asian/Pacific Islander. These conversations took place in the 2021–2022 school year, as teachers across the state grappled with how to interpret and respond to the new legislative constraints on their teaching. At that time, 17 participants were practicing teachers, 11 were future teachers, and three had just completed student teaching.

From these focus group conversations, we learned there were significant effects on classrooms, with teachers feeling the need to restrict the ways their teaching engaged with issues of race, racism, and other forms of oppression. These perceived restrictions, in many cases, extended well beyond the specific topics prohibited in the state legislation. Uncertain how to interpret the law’s vague language and fearful of the consequences of being “caught” teaching a prohibited concept, most teachers we spoke with described how the new law led them to be less confident in their ability to teach about race and racism, and so they expected to subsequently engage in this type of teaching less often.

The law, in other words, functioned precisely as its Republican proponents hoped it would. (For example, model legislation released by Citizens for Renewing America explained that critical race theory bans should also prohibit social-emotional learning, culturally responsive teaching, anti-racism, equity, and multiculturalism.) The law not only prohibited educators from discussing the specific concepts outlined, but also produced a range of chilling effects. Teachers described decisions to constrain their own lessons in response to fears that their teaching would be scrutinized by parents or administrators, restricting their teaching beyond the specific letter of the law. Here, we outline some of these suppressive effects.

How Teachers Interpreted the Policy

As we listened to teachers, we realized that these restrictive effects were produced, in part, through the legislation’s often-vague language. For instance, the law expressly allows both “the impartial discussion of controversial aspects of history” and “the impartial instruction on the historical oppression of a particular group of people based on race.” Although the law’s allowance of these topics might suggest an opening for critical conversations, many teachers pointed to the varied ways that a word like “impartial” would be interpreted by the state. For instance, Ellery, a student teacher who entered teaching to promote justice, reflected on a previous unit she believed she could no longer teach, saying, “I guess I was teaching critical race theory in my lesson about the sanitation strike [in Memphis 1968, when Dr. King was killed]. Obviously, we were thinking critically about race.” Even though the strict language of the bill might not prohibit a lesson about that event, teachers seemed to view any lessons that explicitly discussed racial oppression as vulnerable to challenges.

Another teacher, Marla, worried that the law would require her to change how she taught her kindergarteners about Rosa Parks. Imagining how she might respond to students’ questions, she thought aloud: “She was kicked off the bus because, well, why was she kicked off? Well, why? Oh, because Black people are just seen as less than. How can I state those facts without saying that some people were racist, and some people received adverse treatment because of their race?”

This more restrictive interpretation was common, and we believe precisely the policymakers’ intention.

Similarly, she thought about how she addressed Thanksgiving with her students: “Maybe I was breaking the law to say that it wasn’t this big, old, happy feast.” Although the written policy doesn’t prevent teachers from having such a conversation with students, this more restrictive interpretation of the law was common among the teachers we spoke with, and we believe this restriction was precisely the policymakers’ intention. After all, leaders of the movement to ban so-called critical race theory have been clear in their social media and publications that they aim to make these discussions about race in the classroom considered toxic among the U.S. public.

Marla wondered if she could navigate this tension by emphasizing a distinction between past and present, but she added, “I do feel like it’s a conflict because I don’t want my students to think that this is all forgotten, and it’s all peace and rainbows and happiness. I do feel like it is uncomfortable for me to not connect history to the present because that just seems wrong, you know, like I’m lying.” Marla was right that the law limited her ability to talk about systems of oppression in current events (see box on p. 23), but the policy’s chilling effect is evident in her caution about talking about race at all. Though she still has those conversations, she worries it may be in conflict with the law.

Changes to Curriculum

Other teachers, especially those teaching history and government, identified how their curriculum had been changed by administrators in response to the law. One high school social studies teacher, Isaac, gave a stark example of this. Following the protests for racial justice in summer 2020 spurred by the murder of George Floyd, teachers at Isaac’s school had collaboratively created a series of lessons on racism and anti-racism. In one lesson, students and teachers responded to a video about racial justice protests in Minneapolis that explicitly critiqued media narratives about the so-called “riots” occurring there. When the law went into effect, school-level administrators shelved those lessons in favor of a less overtly political curriculum focusing on historical civil rights struggles rather than contemporary ones. “It’s good for us to talk about that,” Isaac said, “but it’s not the same level” of the discarded anti-racism lessons. Instead, Isaac made space for those conversations with students after class.

Other teachers, however, raised concerns about those spaces beyond the formal curriculum. Brea, a student teacher in an elementary classroom, described a moment when a white student referred to a Black student as a slave, apparently referring to the child’s classroom responsibility to sweep the room. By engaging students in guided conversation about this racism, Brea’s mentor teacher responded in the way that many anti-racist scholars would recommend. Yet, Brea, who wanted to become a teacher precisely because of the opportunity for conversations like this one, worried about the law in that moment, wondering, “Is this actively illegal? Can I not be doing this?” Brea expressed concern that the law would prevent teachers in similar situations from having frank conversations about race and racism with students.

Prospective Teachers Reconsider Career Choice

Although many of the teachers we spoke with focused their attention on how to resist or evade the law, it made some prospective teachers reconsider whether they still wanted to pursue the profession. Many saw teaching as an opportunity to build students’ critical consciousness, and it appeared to them that the law would prevent them from doing this work.

Trish, a new college student considering teaching as a career, saw the policy as erasing history. “[Students might] learn about Martin Luther King and how he had a dream. But they probably won’t learn about how he was against capitalism. They won’t learn about more current events that have to do with Black Lives Matter,” she explained. Trish believed that this type of watered-down curriculum, which she imagined would be the outcome of this policy, wouldn’t prepare marginalized students to navigate and resist systems of oppression that they would face in their lives. Trish evidenced a high degree of critical consciousness and could not imagine teaching anything neutrally.

Her experiences teaching at a youth social services organization illustrated this orientation. Relating to her work with outdoor education, she explained race and racism are relevant to agriculture, citing, for example, USDA discrimination against Black farmers and the role of enslaved people in establishing agriculture in the United States. When she talked about how her students had an interest in basketball, she saw the opportunity to teach about how Black athletes are treated as commodities. For Trish, it was easy to see how race related to everything in the curriculum, and it alarmed her that making those connections might be legally constrained.

Consequently, she struggled to imagine committing to teaching in Tennessee: “It’s like me lying to students, and I don’t even feel comfortable doing that as a teacher. I would be fired.” Later, she expanded, “I just can’t. I can’t do this. I really value being honest with students. I really don’t think I can navigate teaching in such a watered-down type of way.”

“They’ll have to write a better law for it to affect anything that I do.”

Another future teacher, Ivy, shared Trish’s concerns. Although she entered college intending to teach in a Memphis public school, this law led her to wonder if she should just “find some little hippy-dippy private school, so I can teach in peace.” She explained, “I think this law puts a lot of pressure on teachers that genuinely care. That’s very dangerous, trying to disempower people who will be good, culturally responsive teachers.” While Trish ended the focus group wondering if she should teach at all, Ivy decided that she could resist the policy: “They’ll have to write a better law for it to affect anything that I do,” she said, and suggested that she’d lend her name to the hypothetical future case, Ivy vs. Bill Lee [Tennessee’s governor], that might one day challenge the law in court.

Ivy was not alone in her intentions to resist this law. Another future teacher, Sarah, described her refusal to follow the law as a high school history teacher. “I’m ready to get fired for that. To be honest, I think for me, that’s just a part of activism.” While Sarah believed she might get fired for her insistence on historically accurate teaching, other teachers resisting the law were less concerned about this potential consequence. Noting the substantial need for teachers at her school campus, first-year elementary teacher Caroline explained, “I try to find moments where I can insert [topics of race and racism], whether or not my principal is OK with it. I learned very quickly that they’re not going to fire me over things like this.” Like Caroline, many teachers brought up teacher shortages as a source of potential power, concluding that administrators would be reluctant to fire them over their teaching.

Aligning with Standardized Curriculum

Our conversations with teachers also reminded us that these anti-critical race theory laws are not the only force constraining curriculum for teachers and students. Many teachers noted that the standardized curricula they were mandated to follow had already erased many of their opportunities to engage students in critical conversations. These mandates were enforced via pacing guides, classroom visits by school- and district-level administrators, and minute-by-minute curriculum content scheduling.

Xandra, a high school English teacher, described her required curriculum this way. She noted that although the curriculum includes some general engagement with the Civil Rights Movement, such as a story featuring Claudette Colvin, “it was very surface-level. It was just like, ‘she was the first Rosa Parks.’” Although some of the law’s supporters might oppose even the inclusion of a figure like Claudette Colvin, Xandra drew on her own exploration of critical race theory in graduate school to soundly refute that point: “When I think critical race theory, I am talking about how Black women were left out of the entire Civil Rights Movement. . . . or about how Claudette Colvin was not given her props, if you will, because she was a teenage mother.” Here, we understood Xandra to be criticizing how textbooks and other mainstream tellings of history often omitted Colvin’s significant role in the movement. Xandra’s more critical readings of the Civil Rights Movement, as well as of contemporary racism, were absent from her prescribed curriculum.

Xandra’s experiences serve as a reminder that struggles to provide students with opportunities to more critically engage with the world go beyond this most recent legislation. Standardized and whitewashed curriculum, high-stakes testing, and related reforms have constrained such explorations and perpetuated white supremacy for decades. Although many teachers have both the desire and ability to engage in more critical teaching, Xandra noted, “There’s really no time. We have 50-minute class periods, and we have to do this and this and this because we’re tested.” She regretfully added, “I would love to, and the students would too.”

The Intention, Not a Byproduct

Across our conversations, we discovered a plethora of ways that the Tennessee policy affected classrooms. These included teachers’ hesitancy to discuss racial justice with students, programmatic changes to anti-racist curriculum, and teachers with justice commitments struggling to remain in (or enter) the profession. Rather than unintended consequences or misinterpretations of the law, however, these effects are in fact the goal for conservative lawmakers who have promoted color-blind approaches and made clear their belief that talk about race is racist. (For instance, see Citizens for Renewing America’s online guide, Combatting Critical Race Theory in Your Community, that takes this stance.)

It doesn’t matter that the laws don’t actually make it illegal to tell an accurate story of “the first Thanksgiving”; it matters that teachers worry that it might, so they censor themselves. The laws give cover to groups wanting to object to any form of anti-racist teaching, so schools change their curriculum to avoid these confrontations. Gag orders work because of their vagueness and the nebulous legal climate they create.

A review of how these laws have been enacted nationally illuminates why the teachers we spoke with were concerned with how to teach under the new policy. In Georgia, a new DEI administrator was harassed into resigning. Teachers in New Hampshire felt the need to obtain parental permission before viewing Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in class. A parent in one Iowa district demanded that the high school elective course “Social Justice in Literature” be discontinued. And teachers and administrators in multiple states have been fired for their discussions about race and racism.

Teachers Fight Back

Ultimately, when censorship prevails, educators lose ground as professionals with authority and judgment to design curriculum. And students lose the opportunity to make sense of racial injustice through connecting the past to the present with an educator’s guidance.

This type of policy climate for teachers demands organized resistance. Teachers in our study often talked about resistance as an isolated endeavor. But when educators work alone, we lose. It is through coordinated efforts — like the Pledge to Teach the Truth, local union organizing, participation in national professional organizations, and involvement with local school boards — that teachers most effectively fight back.

As of January 2023, more than 8,500 educators had pledged to teach history honestly via the Zinn Education Project, which compiles teaching materials, news, and campaigns. In June 2022, Neighbors for Education sponsored a rally at a local museum for teachers, parents, and other stakeholders in response to curriculum bans. More recently, in Faulkner County, Arkansas, parents, concerned community members, and students protested at a local school board meeting against a proposed curriculum policy that would ban divisive concepts like critical race theory, gender identity, and sexual orientation. This school board meeting protest followed a walkout at the local high school led by students against the proposed policy. Nationally, the College Board piloted an AP course in African American history in 60 U.S. high schools, which could include content banned by current laws and policies. One teacher in our focus groups told us her administration had told teachers: “We stand against this [policy]. We’re an anti-racist organization.”

Resistance can also be incubated through study groups or learning communities where teachers come together to critically analyze the specifics of a law and reflect on their position within that context. In our focus group conversations, teachers read and discussed the Tennessee bill, and many found that the written policy was not quite as restrictive as they had feared. Some teachers pointed to the exceptions in the bill for discussing racism in the context of history as a “loophole” (see box on p. 23) to continue teaching about racism. Teachers might consider holding similar study groups to examine their state policy, and teacher education programs could host spaces where future teachers have collaborative conversations to identify opportunities for resistance.

Based on what we learned from our focus group conversations, we held a campus-wide panel to provide information on the law and identify opportunities to resist the law both within and beyond the classroom. We continue to bring these conversations into our teacher education classrooms, and have adapted our courses to teach teachers how they can affect educational policy through working in unions, participating in school board meetings, and pressuring elected officials. We are also inspired, for instance, by the decision of teacher educators at Cal State Fullerton to halt placement of student teachers in the Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District, where trustees voted to ban critical race theory. What are other institutional-level actions we can take to resist?

Educators can and must collaborate to resist and push for the repeal of these policies. As the teachers we spoke with affirmed over and over, “Kids can talk about hard things,” and their right to do so in school is worth fighting for.

The prohibited concepts in Tennessee’s SB0623 are:

- One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex;

- An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously;

- An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment because of the individual’s race or sex;

- An individual’s moral character is determined by the individual’s race or sex;

- An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex;

- An individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or another form of psychological distress solely because of the individual’s race or sex;

- A meritocracy is inherently racist or sexist, or designed by a particular race or sex to oppress members of another race or sex;

- This state or the United States is fundamentally or irredeemably racist or sexist;

- Promoting or advocating the violent overthrow of the United States government;

- Promoting division between, or resentment of, a race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class, or class of people; or

- Ascribing character traits, values, moral or ethical codes, privileges, or beliefs to a race or sex, or to an individual because of the individual’s race or sex.

The law goes on to say that instructional materials that include the following are allowed:

- The history of an ethnic group, as described in textbooks and instructional materials adopted in accordance with present law concerning textbooks and instructional materials;

- The impartial discussion of controversial aspects of history;

- The impartial instruction on the historical oppression of a particular group of people based on race, ethnicity, class, nationality, religion, or geographic region; or

- Historical documents that are permitted under present law, such as the national motto, the national anthem, the state and federal constitutions, state and federal laws, and Supreme Court decisions.

Reference

Hamilton, V. E. 2021. “Reform, Retrench, Repeat: The Campaign Against Critical Race Theory, Through the Lens of Critical Race Theory.” William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice 28.1.