The Character of Our Content

A parent confronts bias in early elementary literature

Illustrator: Brent Nicastro

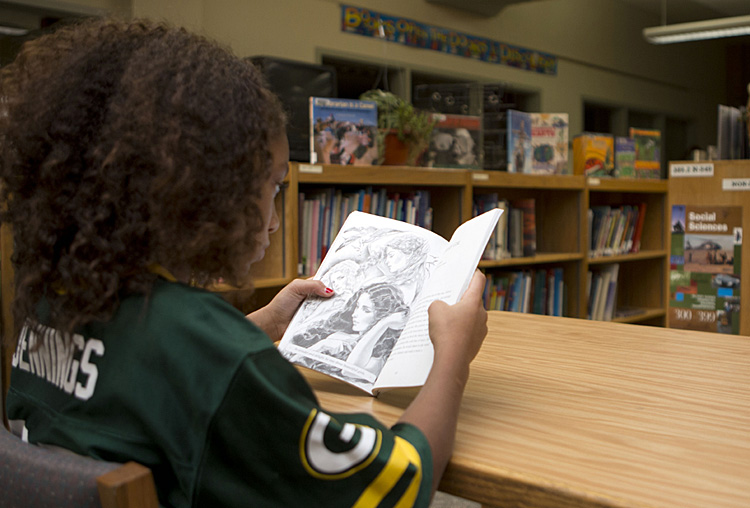

Last spring, my 2nd-grade daughter came home with an extra assignment—a worksheet she hadn’t completed in class for a story called “The Selkie Girl.” She brought the book home, too, and it was one I’d never seen before, a Junior Great Books anthology (Series 3, Book 1), published by the nonprofit Great Books Foundation.

As we settled in, I asked my daughter to tell me about “The Selkie Girl.” Her rendition gave me pause, so I asked her to do her other homework first. She turned to a worksheet, and I cracked the book open.

“The Selkie Girl” is essentially about a magical seal-woman who is kidnapped and raped repeatedly during her long captivity. The man who holds her hostage proclaims early on that “I am in love” and “I want her to be my wife.” When he kidnapped her, “She was crying bitterly, but she followed him.” Later, the narrative tells us, “Because he was gentle and loving, she no longer wept. When their first child was born, he saw her smile.” When her means of escape is discovered, however, she explains quite bluntly to the children she bore: “For I was brought here against my will, 20 years past.”

It’s like the modern-day reality of Jaycee Dugard (who was kidnapped at age 11 in California and held captive with her two children for 18 years), told in folklore for the consumption of young children.

The white beauty norms in the story do not help, either:

He went to look and, in wonder and delight, he saw three beautiful girls sitting on the rocks, naked, combing their hair. One of the girls had fair hair, one red, and one black. The fair-haired girl was singing. She was the most beautiful of the three, and Donallan could not take his eyes from her. He gazed and gazed at her gleaming white body and her long-lashed dark eyes.

When I asked our daughter about the “messages” of the story, she pointed to this passage and the accompanying illustrations as support for the idea that she—an African American girl—is “not pretty.”

I was astonished, and I kept reading.

Not all of the book’s stories are horrible in an anti-bias sense, but the social norms conveyed by the text as a whole are. A third of the stories with human characters have female leads, but men—their virtue or their needs—actually dominate all of them. Further, nearly all women and girls are referred to as “wife,” “mother,” or “daughter,” and that is understood to be the genesis of their power, standing, or importance. Men and boys, meanwhile, are presented in a multitude of ways. Finally, the volume’s portrayals of poverty and its supposed causes—“[He] lived in the smallest hut of his village, and if he had been lazy he would have gone hungry at night”—are troubling, as is the recurring theme of obedience to the powerful.

Getting a Pass into Class

How could this book make its way into an early elementary classroom?

First, Junior Great Books easily pass the “research-based” test. On the publisher’s website, you’ll find a slew of studies about the series’ positive effects. As summarized on the Great Books Foundation’s 2011 990 tax return, “the K-12 program has significantly impacted reading levels in reading comprehension on state and national standardized tests.” A pedagogical approach called “shared inquiry” that directs the accompanying teachers’ guides also is backed by research: “Studies have also shown that the skills acquired by shared inquiry have transferred to other content areas, thus impacting achievement levels on tests in areas such as math and science.”

Second, the series is aligned to individual state standards and to the Common Core. The state in which we live recently adopted the Common Core, and educators here are spending an untold number of hours realigning desired instructional outcomes to them. The Junior Great Books—marketed as “the cure for the Common Core!”—are more than welcome in this regard.

Third, the foundation promises access to “readings of high literary merit that are rich in discussible ideas” and touts selections from award-winning authors. My daughter’s book includes a story by Anne Sibley O’Brien, who has received the National Education Association’s Author-Illustrator Human and Civil Rights Award and the Aesop Prize, as well as a selection from storyteller Diane Wolkstein, recipient of the National Storytelling Association’s Circle of Excellence Award.

Fourth, the series is marketed as appropriate for use with diverse learners. All images, videos, and samples on the foundation’s K-12 website feature racially and ethnically diverse students, an important selling point for most public schools.

So it’s not surprising that many schools are taking advantage of these offerings: “The K-12 program provides low-cost educational materials to over 5,000 schools with more than 1,000,000 students.”

Unfortunately, the adoption of these materials reflects a trend that extends well beyond Junior Great Books themselves. Concerns about the “narrowing of the curriculum” under No Child Left Behind (NCLB) often focus on the short shrift given to subjects like social studies, music, and art. The truth is that curriculum is also narrowing in language arts and math classrooms, where content increasingly is restricted to materials, like Junior Great Books, that are “proven” to boost test scores. School purchasing decisions have become highly dependent on products’ alignment with standards and the presence of a “skill-supporting research base.”1 In the elementary context, 92 percent of teachers report that their districts have implemented “curriculum to put more emphasis on content and skills covered on state tests used for NCLB.”2

Reflecting Conservative Norms?

I was unable to find any criticism of Junior Great Books in general or of “The Selkie Girl” in specific. (This latter absence may reflect the fact that the most recent copyright date for a story in my daughter’s book is 1993.) That said, there were two things I discovered about the Great Books Foundation that might give someone pause.

The foundation was established in 1947 with the goal “to encourage Americans from all walks of life to participate in a ‘Great Conversation’ with the authors of some of the most significant works in the Western tradition.” Its Junior Great Books program, launched in 1962, relied heavily on excerpts of selections—including Pilgrim’s Progress and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—from the original adult program. Although the foundation’s canon certainly has expanded over time, its genesis as an advancer of the male- and white-centric “Western tradition” raises a yellow flag.

The foundation’s board of directors is chaired by Alex J. Pollock, who works at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), one of the nation’s most influential conservative think tanks. Mr. Pollock’s expertise lies in financial policy issues, but, as the Southern Poverty Law Center has noted, “While its roots are in pro-business values, AEI in recent years has sponsored scholars whose views are seen by many as bigoted or even racist.”3

For example, longstanding AEI fellow Charles Murray is best known as co-author of The Bell Curve, which infamously argues that whites are inherently more intelligent than blacks and Latina/os. He has argued forcefully elsewhere that the nation’s interests are best served, not by affording all children access to a quality education through college, but by focusing on the needs of “gifted” children. Meanwhile, AEI’s longtime resident expert on gender issues is Christina Hoff Sommers, widely known for her scathing critiques of contemporary feminism. Hoff Sommers has strongly criticized what she sees as an anti-boy culture in schools, specifically the use of “feminized” literature.4 More broadly, AEI exercised significant influence over the policies established under the second President Bush. As People for the American Way notes: “President George W. Bush appointed over a dozen people from AEI to senior positions in his administration.”

All of this prompted me to ask: What kind of values are likely to be promoted in school materials created by an organization whose board chair works for a rightist think tank?

Exactly the kind my daughter encountered in her Junior Great Book.

We Endorse What We Teach

In purchasing Junior Great Books as supplements for language arts classes, teachers and school leaders surely possess good intentions. They seek to provide students with what is described as engaging content while helping students build up their reading and writing skills.

As schools place greater and greater emphasis on documenting skill-based outcomes, I really do understand how and why a teacher might focus more on what a child writes on a test, rather than the content on which the test is based. I understand how problematic content might slip through, and I believe few, if any, educators would welcome a story like “The Selkie Girl” into an early grades classroom if given the support and time to reflect on it first.

We—parents, educators, school leaders, and educational publishers—possess a collective responsibility to evaluate the character of the content as rigorously as we evaluate children’s “learning outcomes.” We must deliberately create space to reflect, because the material we place before children and thus endorse in our classrooms teaches much more than comprehension skills. The social messages and values children take away from the content—the what of their comprehension—matters.

At my daughter’s school, raising these issues resulted in the text’s immediate removal from classrooms—and a renewed commitment to evaluating the character of our content. A group of our teachers spent their summer taking a fresh look at our curricula, with eyes, ears, and hearts clearly focused on identifying bias and the broader communication of problematic social norms. These are needed steps within our school community, and they are steps other schools may need to undertake as well.

Endnotes

- Educator Buying Trends: How Teachers Make Buying Decisions, A National Survey, Market Data Retrieval, 2007.

- McMurrer, Jennifer. NCLB Year 5: Choices, Changes, and Challenges: Curriculum and Instruction in the NCLB Era. Center on Education Policy, 2007.

- Berlet, Chip. “Into the Mainstream,” Southern Poverty Law Center Intelligence Report, Summer 2003.

- Benfer, Amy. “Lost Boys,” salon.com/2002/02/05/gender_ed. See also Hoff Sommers, Christina. The War Against Boys: How Misguided Feminism is Harming Our Young Men. Simon & Schuster, 2000.