The Attack on Anti-Racist Teaching Is an Attack on Environmental Justice Teaching

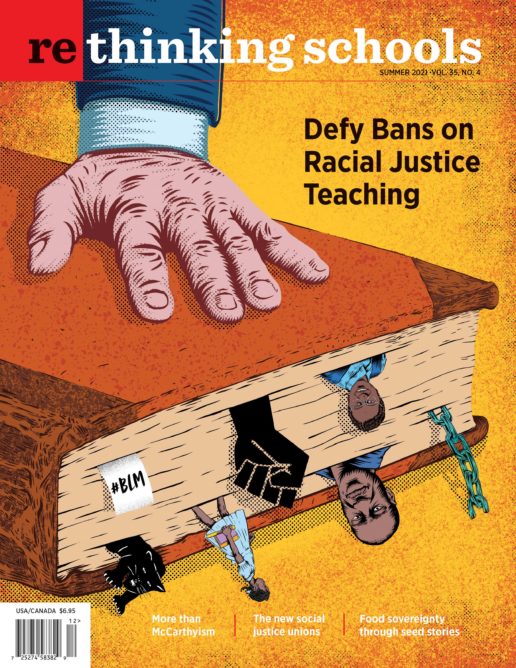

Illustrator: Erik Ruin

In his magnificent new book, How the Word Is Passed, Clint Smith quotes the Rev. Dr. William Barber II: “The same land that held people captive through slavery is now holding people captive through this environmental injustice and devastation.” But why? Why do race and environmental devastation align so neatly?

In an increasing number of states, it is illegal for teachers to engage students in attempting to answer this question.

As we describe in this issue’s editorial, legislators in more than 20 states have passed laws — or are attempting to pass laws — to prohibit teachers from putting racism at the center of their classroom inquiry about the nature of U.S. society. It is now a crime for a teacher in Iowa, for example, to suggest that the United States is “fundamentally or systematically” racist.

But the hailstorm of legislation attacking anti-racist education has a less obvious target: teaching about the environment and about climate change. One of the most extreme pieces of legislation is Missouri’s House Bill 952, which explicitly bans the use of Zinn Education Project (ZEP) lessons in all of the state’s public schools. (ZEP is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.) This would outlaw our lessons on the Tulsa Massacre, the U.S.-Mexico War, and Reconstruction. But it would also prohibit teachers from using every lesson, article, and other resource at ZEP’s Teach Climate Justice Campaign — arguably the most comprehensive online collection of climate justice teaching materials.

These include lessons that emphasize the unequal impact of a fossil fuel-driven economy and the climate crisis on Indigenous peoples. “‘Don’t Take Our Voices Away’” is a role play that focuses on the first gathering of Indigenous peoples to share experiences of how climate chaos is ripping through their communities, and to make demands of the wealthy countries that are the main source of this devastation. “Standing with Standing Rock” helps students recognize the fossil fuel invasion of Sioux territory in a long history of land invasions, broken treaties, and white aggression against Native people in the United States. Other ZEP lessons similarly center the impact of climate change and environmental degradation on people of color. The proposed law would deny teachers the right to use all these resources.

The racial inequality that any environmental justice curriculum seeks to expose and critique is not the invention of critical race theorists. It is the product of the long history of white supremacy and colonialism — which began in the Americas with Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of the Taíno people, whom he called “the best people in the world . . .” — a people who “love their neighbors as themselves . . .” Columbus wrote these words and then proceeded to colonize, enslave, and brutalize — and put nature at the service of greed. Colonialists razed forests in favor of sugarcane, introduced pigs that rooted up Taíno crops, and began cattle ranching and a plantation agriculture system that “exposed the surface soils to wind and water erosion far more drastically than the Taínos’ careful conuco [mound] planting,” according to Kirkpatrick Sale in The Conquest of Paradise. The Spaniards’ arrival marked the beginning of “ecological imperialism” in the Americas. The attack by white people on people of color and on nature were inseparable. This environmental racism is “fundamentally and systematically” part of our society’s DNA — stretching back to 1492 — and yet is now illegal to study in an increasing number of states.

Climate Illiteracy

The right-wing legislation would deny students climate literacy. Racial inequality — and the struggle against it — is at the heart of the climate crisis. Roles describing two people who live in Miami in “Stories from the Climate Crisis,” a mixer activity included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth and at the Zinn Education Project, offer one glimpse of how racism is implicated in climate change. As seas rise, housing prices in higher-ground neighborhoods in Miami are going up three times as fast as beachfront property. The white real estate speculator Tom Conway is buying up property in these predominantly low-wealth neighborhoods of people of color, like Little Haiti and Liberty City, ruthlessly evicting tenants who have made their homes and businesses there for more than 30 years. Paulette Richards, an African American woman, lives in Liberty City. She struggles to hold on to her home in the face of what activists call climate gentrification.

The right-wing legislation would deny students climate literacy.

This one small drama is both an instance of, and metaphor for, how racism is at the center of the climate crisis. At its root, climate change is driven by investment and political decisions of predominantly white people striving to increase their wealth, and then exploited by other predominantly white people (like Tom Conway), who profit from disaster. All of us live with the consequences — but especially those who have been on the receiving end of slavery and colonialism, whether in Liberty City (like Paulette Richards), Puerto Rico, the Marshall Islands, Bangladesh, Zambia, or the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. Climate literacy requires educators and our students to reflect on how racism shapes both the causes and effects of the crisis.

It also demands that we engage students in considering what to do about the climate crisis — and how potential solutions could intersect with solutions to other social problems. How, for example, could a Green New Deal simultaneously address climate change, joblessness, immigration justice, houselessness, and racial inequality? An honest, rigorous look at the enormity of climate chaos threatens to turn our classrooms into dens of cynicism. Only activism can inoculate our students against despair. And yet one Texas bill that is part of the collection of silencing measures around the country seeks to prevent teachers from encouraging social and environmental activism. House Bill 3979 calls for sweeping prohibitions against student activism. Part of the bill reads: “No school district or teacher shall require, make part of a course, or award course grading or credit including extra credit for, political activism, lobbying, or efforts to persuade members of the legislative or executive branch to take specific actions by direct communication at the local, state, or federal level, or any practicum or like activity involving social or public policy advocacy.” Pause for a moment to reflect on the breathtaking nature of these restrictions.

This curricular gag rule is aimed at civil rights and racial justice activism — and no doubt at students’ involvement in agitating for the removal of racist iconography in Texas. Climate justice activism is collateral damage — but devastating, nonetheless. The fall before the pandemic, Sept. 20, 2019, saw the biggest student strikes for climate justice in history. The Texas bill, and others like it, would keep students in the classroom and out of the streets — and away from experiencing the efficacy that comes with being part of a social movement.

When we talk about “teaching climate justice,” a key piece of this means that we focus on how the crisis is crashing unequally throughout the world, highlighting the voices of those who are hit hardest and who have the fewest resources to stave off catastrophe — as well as emphasizing the resilience and resistance of these marginalized communities. And teaching climate justice also means engaging students in a search for the roots of this inequality. Inevitably, real teaching — teaching that prompts students to search for explanations and imagine solutions — will come into conflict with laws that ban putting racism at the center of our inquiry.

So there is our choice: We comply with laws that require us to make our students ignorant, or we attempt to teach the truth about the intersection of racism and environmental harm — and urge students to get into the world and make a difference.