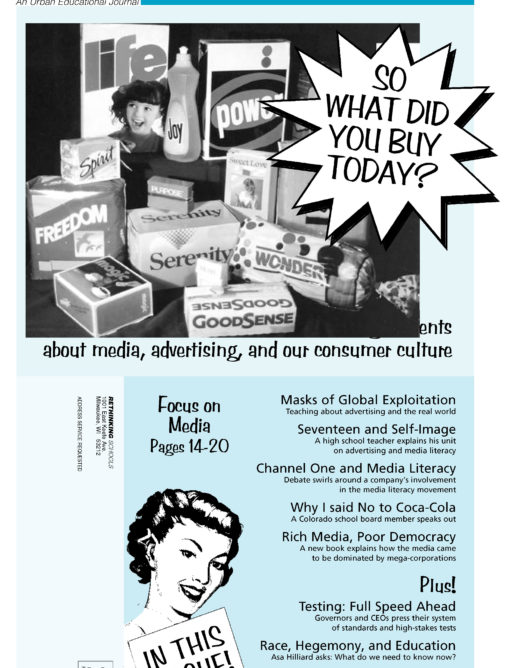

Preview of Article:

Testing

A Report on the National Education Summit

The meeting at the IBM headquarters was billed as the third National Education Summit. The first was in 1989, when President George Bush convened 49 of the nation’s governors and established Goals 2000. (None of the goals – which ranged from wiping out adult illiteracy to making U.S. students the world’s top achievers in math and science – are yet within reach.) In 1996, at the second summit, corporate leaders were brought on board and a more focused agenda was set, based on standards and accountability.

While calls for standards and accountability pre-date the 1996 summit, the governors and business leaders took the standards movement and reshaped it in their image. With calls for national standards stymied by opposition from both the right and the left, and with district and school-based efforts deemed too prone to influence from teachers and educators who conservatives had decided were part of the problem, the governors and corporate leaders forged ahead on the state level. They set up state standards, often heavily influenced by conservative ideologues and think tanks. Perhaps most important, they decided that high-stakes standardized tests were the best way to determine if schools were reaching the standards. (One of the most interesting yet untold stories of the history of standards is how the governors and corporate leaders, aided by conservative think tanks, took over the standards movement and transformed it into a top-down process that establishes an official version of knowledge and sets back efforts to forge a multicultural vision, in the process valuing discrete facts, memorization, and “basics” over critical thinking and in-depth understanding. But that is another story.)

Since 1996, the governors and corporate leaders have had an impressive track record – not so much in guaranteeing true reform and academic achievement, but in setting up their system of standards and high-stakes tests. At the time of the 1996 summit, only 14 states had established state standards in the four core academic subjects. By the next school year, 49 states will have such standards. (Iowa, which consistently scores at the top of various national academic measurements, is the only hold-out, prompting the comment from author and anti-testing advocate Alfie Kohn, “Thank God for Iowa.”) Furthermore, the number of states that will be requiring students to pass high-stakes tests in order to be promoted or to graduate has jumped in the last three years from 17 to 27, and summit leaders are pushing to increase that number.

The governors and corporate leaders are quick to cite such statistics as proof of reform. On one level, that’s not surprising. Both groups exist in a world where bottom-line numbers are all that matter: you either win an election or lose; your profits are either up or down. It seemed to escape conference leaders that the complexity of school reform cannot be so easily captured in hard-and-fast numbers. (A distinction must be made between the conference leaders and sponsors – the governors and business leaders – and the co-sponsors and invited guests, which included representatives of educational organizations. The true power rested with the corporate leaders and governors. A number of those invited seemed to realize that to not take part would leave them on the sidelines of what is the main game in education reform, unable to influence the proceedings and unable to use the summit’s promise of “high standards for all” as a way to possibly leverage more resources for education and underscore the importance of teacher training and quality.)

There was a disorienting disconnect between the conference setting and the reality of most U.S. classrooms. As in 1996, the summit was held at IBM headquarters, a feudal-like conglomeration of office buildings and well-manicured grounds just north of New York City. It is a self-contained world, complete with restricted entrance (not even taxicabs were allowed onto the grounds), helicopter landing pad, swans and goldfish lazily swimming in a moat-like stream, guest hotel (reportedly with computers in every room), health spa, game room (also with computers), and gourmet dining facilities.