Test Prep and the War

Preparing high schoolers for the Regents exam while studying the War in Iraq

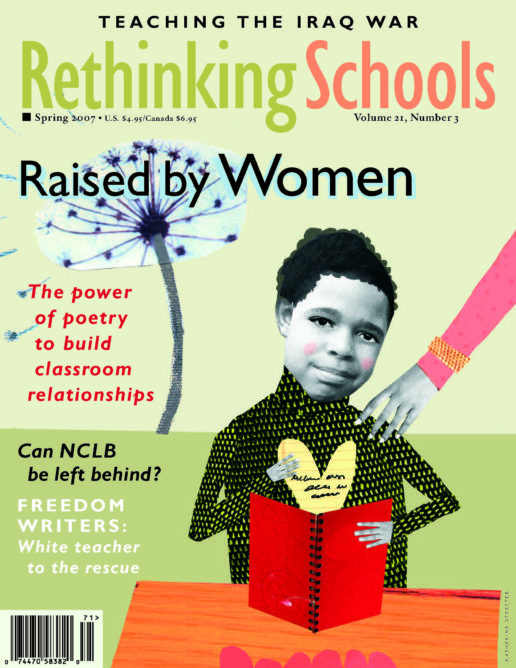

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

“You continue saying ‘we.’

Who is ‘we’ when you are not fighting in Iraq yourself?”

“We have many weapons. Do you feel it would be right

for another country to disarm us?”

“If we ignored Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons in

the past, why do we care now when he isn’t using them?”

My students asked these questions — more difficult than those posed by the U.S. media — during a role play in which I pretended to be President George W. Bush giving his 2003 State of the Union address a few months before the U.S. invaded Iraq.

The mock press conference was part of a unit in which I blended studying about the war with preparing my students for the New York State English Language Arts Regents Exam, which they must pass in order to graduate. Despite the usual misgivings about what I could and should have done better, I felt pleased that I had been able to meld such an important topic with the district’s impossible-to-avoid curricular focus on test prep.

I teach 11th grade English in Brooklyn at a high school serving a low-income, predominantly Latino population. Every year I have to prepare my students, many of whom are English language learners (ELL), for the Regents Exam. Because half of the exam is based on nonfiction writing, I decided to create a nonfiction unit that focused on the war but that would also allow my students to practice skills they need for the Regents in summarizing, annotating, note-taking and responding to nonfiction writing.

The first day of what became an almost month-long unit, I asked students to write down everything they knew about the war. We then shared the writings aloud, giving me a sense of the students’ level of understanding. Some students thought Iraq was responsible for the 9/11 attacks, while others knew that Osama bin Laden had no relationship with Iraq. Some didn’t even know where Iraq was.

Overall, students were overwhelmingly against the war and hostile towards the Bush Administration. At the same time, a number were considering joining the military after high school and would undoubtedly end up in Iraq. I felt I had a responsibility to ensure that they would be able to make informed choices about their future after high school.

In almost all of my classes, three reasons for being in Iraq showed up on the students’ lists: 1. We are bringing democracy to Iraq; 2. We are stopping terrorism and getting rid of weapons of mass destruction; and 3. Our government wants oil and political control over the Middle East. Before we examined those different reasons, I wanted to address the issue of the media, in particular how to determine whether a news source is reliable.

I asked my students, “How do we know when we are getting the full picture?” I was surprised by the frustration and cynicism in many of their answers: “You can’t believe anything the television tells you.” “The president says this and somebody else says that. It’s impossible to know who to believe.”

It was clear that my students needed to see that it was possible to critically evaluate the information they received and to develop informed opinions about the war. I also wanted them to acquire an understanding of the history and politics that led to the war, so they would be aware of the distortions, omissions, and outright lies in much of the U.S. mainstream media coverage.

Summarizing Different Viewpoints

One of the most successful media-related lessons involved an exercise where we compared two media viewpoints. First I showed the first 20 minutes of Control Room, a documentary about Al-Jazeera, the international Arabic-language television network headquartered in Doha, Qatar. Students were shocked by the dead bodies and destruction shown on Al-Jazeera. For many it was the first time they realized that it wasn’t just soldiers who died in war.

For homework, students were to find a U.S. newspaper story about the war and summarize it using the Someone-Wants-But-So strategy — a summarizing strategy where students create a string of sentences in order to summarize a text. This strategy requires students to identify the “main player” in a piece of writing (the “someone”), his or her motivation (“wants”), the conflict (“but”), and the resolution (“so”). Summarizing in this way was useful for preparing students for the upcoming exam, where they will have to summarize unfamiliar information in an essay.

In the following class, we discussed how the viewpoints differed. Students found that, understandably, Al-Jazeera was more concerned with Iraqi lives and interests and with opinions in the Arab world. U.S. newspapers, meanwhile, were more concerned with lives of U.S. soldiers and debates within the U.S. government. While a few students thought that the Arab media “showed the reality of the war… things ‘us’ Americans are not shown by our media,” most were reluctant to say that any news source was more or less reliable than any other. As one student put it, “The Arab news shows things that put Americans in a bad light and American news shows things that put Arabs in a bad light. Each news favors their own.”

My goal was not for students to decide that Al-Jazeera was either a better or worse news source than the New York Daily News or the Fox Broadcasting Company. Rather, I wanted my students to see that the news we are regularly exposed to is not telling the “whole story” about the war. In retrospect, there were a number of problems with this exercise. One is that each student looked at a different U.S. article on a different topic (Saddam’s trial, the death of a U.S. soldier, etc.) while the Al-Jazeera coverage was about the beginning of the war. Also, I did not carefully distinguish between bias (and its connotations of prejudice and distortion) and point of view, which is present in any reporting. In the future, I would be more targeted in looking at information, perhaps taking a specific situation and comparing media coverage from a number of sources.

Annotating Background Information

It was clear from our look at the news media that my students needed additional background information. I adapted an exercise from Whose Wars? Teaching About the Iraq War and the War on Terrorism by Rethinking Schools on the history of Iraq/U.S. relations. I shortened the selection of situations from 10 to six and simplified the language for my ELL students.

Working in pairs, students read each situation and selected the response they thought the U.S. government should take from a list ranging from “use military force” to “officially criticize actions” to “support with economic and humanitarian aid.” I made it clear that I did not want them to decide what our government would most likely do, but rather, what they thought was the right thing to do. I gave the students a brief explanatory paragraph for each situation and students annotated each paragraph, underlining key ideas and writing their thoughts and questions in the margins. This kind of careful annotation is an important strategy for students when taking the Regents Exam.

The next day, I gave students a one-page document with the actual U.S. responses. We went over these as a class, and students continued to annotate. Even with simplified language and working in pairs, many of the less-skilled readers had enormous difficulty working through these adapted texts. With little or no prior knowledge of Middle Eastern history, nor much experience untangling complex geo-political situations, many of my students struggled to understand the various interactions between Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the United States over the past 25 years. Even so, students drew some important conclusions from trying to decide the right choice for the United States to make in each situation.

Afterward, students wrote in-class personal responses, choosing from a list of questions I provided such as: How has U.S. policy in Iraq been consistent or inconsistent? How do the U.S. government decisions of the past help you answer the questions you have about the current war?

Many students were disgusted with U.S. actions in Iraq. One student wrote, “Helping other people is a great thing but when you’re helping others that are trying to hurt others [supplying chemical weapons agents to Iraq during the war with Iran], that makes you as bad as them.” Overall, students felt that historically, the U.S. government had primarily acted to protect its own interests in the region and not to promote human rights or democracy. This led some students to note that in protecting its interests, sometimes the U.S. government had supported Hussein and other times it had attacked him.

Note-taking and Questioning

One of the most interesting activities involved watching the documentary film Fahrenheit 9/11 by Michael Moore. Politically, the documentary not only provided additional background information but addressed the question of whether the U.S. government’s interests are the same as the interests of people living in the United States. Academically, it provided a chance to improve student skills in note-taking and questioning.

As the students watched the film, they kept notes on a graphic organizer I provided for them. In particular, I had students keep notes on memorable lines from either Moore or the people he interviewed. Because part of the Regents Exam requires students to take notes on a passage read aloud to them (but that they never get to read themselves), this note-taking practice was especially important.

Afterward, I put some of the lines they selected (along with some of my own) on pieces of chart paper that I put up around the room (another exercise from Whose Wars?). I read aloud each quote and then passed out Post-it notes. The students went through a few rounds of responding to the quotes with their Post-its, and then responding to each other’s responses, all without speaking. Later, I opened it up to a class discussion by asking for students to speak on anything they had read that struck them deeply. Depending on the class, these discussions spanned a number of topics — from concerns about military recruitment to whether things would be different if we had a black president.

Fahrenheit 9/11 is a great film for bringing up issues around the causes and the consequences of the war. It lays out and documents, with real people and actual corporations, the ways in which this war has been waged to profit the few at the expense of the many. However, I wanted my students to develop a critical eye toward sources of information on the war, even ones they might be sympathetic to.

Toward that end, we spent a few class periods looking at logical fallacies such as slippery slope, red herring, and the straw man argument. We practiced identifying these fallacies in a number of non-Iraq war-related examples, and then I asked them to think back on the documentary to identify any logical fallacies.

They quickly identified the ad hominem attacks in the form of cheap shots and still photos of the president looking awkward. They saw Moore’s mockery of smaller and less powerful countries involved in the “Coalition of the Willing” as a red herring. One student noted that Moore conveniently left out Great Britain from his list of countries in the coalition — a fallacy of omission. Some students also felt that Moore employed a bit of a slippery slope in linking the Bush family’s relations with the bin Laden family to an all-out war in Iraq.

Before moving on to the unit’s culminating exercise — a mock Regents Exam essay — it was time for the students to hear from the president himself.

In another exercise from Whose Wars? I pretended I was the president and my students were the media. They listened to me read the 2003 State of the Union address while they had a copy in front of them. In the press conference that followed, they asked me questions. In responding, I tried to use a number of logical fallacies, including some from Bush’s actual State of the Union speech.

The students thoroughly enjoyed “grilling” the president, but were also frustrated by their inability to get straight answers. After the press conference, students wrote in-class response papers about their thoughts and opinions on the war. As before the unit began, most were against the war and critical of Bush. But now their opinions were based on a more solid understanding of the war and the history of U.S./Iraq relations.

As one student wrote, “[This unit] has opened up a whole new thing to me, because before I even saw the video [Fahrenheit 9/11] on Iraq I was interested, but not as much as I am now. I mean, when I heard that they were bombing Iraq, I didn’t realize the deaths and pain the women and children were going through. It opened my eyes.”

Writing Exam Essays

To end the unit, I created a mock Regents Exam essay assignment, in which students read a nonfiction essay, examine a chart or graph, and then respond to show that they understand what they had read. I used the format of countless Regents essay exams I have seen over the years and created this situation:

The students in your class are presenting information to each other about the current war in Iraq. To prepare the class with information on different aspects of the war, your teacher has asked each student to write a report explaining a specific aspect of the war.

In groups of three or four, students selected a specific topic about the war from a list that included cultural/ethnic tensions in Iraq, the role of oil, and military recruitment. Each group received an article and a map, chart, or graph about their topic. To understand the materials, students used the summarizing, annotating, note-taking, and questioning techniques we had practiced throughout the unit. Based on this information, they then individually crafted a straightforward informational essay.

In some ways, the essay was a let-down as a final assignment because the Regents essay format does not allow for students to express their own opinions or to bring in much outside knowledge, which leads to drab, formulaic writing. I generally felt good about the content of what we had studied in the unit and that my students had been able to practice important skills such as summarizing, note-taking, and annotation. Yet I realized they had shortcomings in preparing students for the Regents Exam. Clearly, blending important curricular content with a prepackaged high-stakes test is not easy.

The exam requires students to read a nonfiction passage on a topic where they may not have any prior knowledge. In our unit, however, students studied and then wrote about the same topic. While this undoubtedly helped students develop their reading comprehension skills, I wonder if it will help them write about possible topics on the Regents essay such as irrigation. Or the history of vaudeville theatre. Or manatees.

Indeed, in this unit my students had the luxury to write about something they cared about and had studied — rather than the Regents approach of writing on something you may care nothing about, or know nothing about, and do so for 90 minutes. This, of course, brings up the question of what is most important to know how to do before graduating high school.

Overall, I felt this unit engaged students on a topic they were hungry to understand. When I compared their questions at the beginning of the unit to their questions for Bush during the press conference, I saw how they moved from general distrust and cynicism toward very specific questions that showed a more in-depth understanding of the war. And such specificity is essential to overcome generalized feelings of cynicism and hopelessness, not just about the war but other issues, such as racism and poverty, that the war exposes. Being able to understand how history unfolds helps students think about how things might be different and what would need to be done to make changes.

I hope that detailing my experiences with this unit will encourage other teachers to share their ways of dealing with the dreariness of test prep while still keeping their teaching vibrant and their curriculum relevant.

RESOURCES:

Control Room

Directed by Jehane Noujaim

(Lions Gate, 2003)

Fahrenheit 9/11

Directed by Michael Moore

(Sony Pictures, 2003)

Whose Wars?

Teaching About the Iraq War

and the War on Terrorism

(Rethinking Schools, 2006)

80 pp. $12.95

WEB RESOURCES

for reports, graphs, maps and charts on Iraq

http://nationalpriorities.org

The National Priorities Project is a nonpartisan, nonprofit group providing educational information on the impact of federal tax and spending policies at the community level. Oversees the costofwar.com site.

http://english.aljazeera.net

The English-language portal of Al-Jazeera.

www.globalpolicy.org

Global Policy Forum is a nonprofit group with consultative status at the U.N., founded in 1993 to strengthen international law and create a more equitable and sustainable global society.

www.nationalgeographic.com

Good basic information on Iraq, including printable black-and-white maps.