Teaching While Undocumented

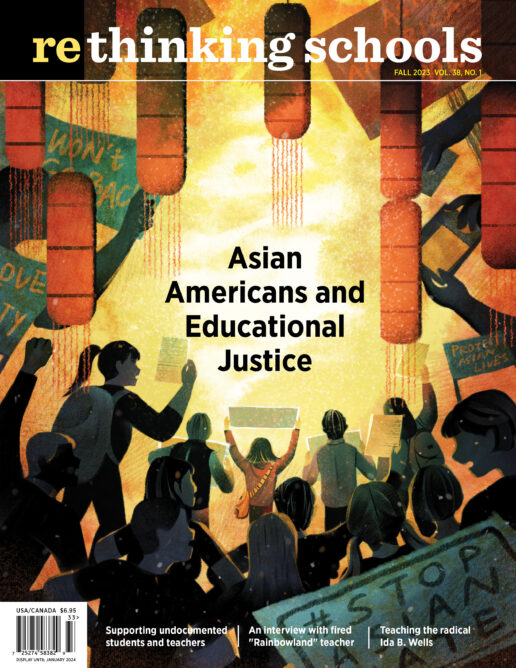

Illustrator: Zeke Peña

Following what she described as a traumatizing border crossing, Daniela and her family moved around a lot. In total, she counts attending eight different elementary schools across two states. Daniela shared her experiences with us as part of a research project focused on undocumented teachers. When Daniela’s family moved to the South, she was surrounded by white classmates and belittled for not speaking English.

The message, Daniela said, was clear: “I wasn’t part of their community.” Through tears, she recalled a painful episode when a racist teacher wouldn’t let her use the bathroom because she couldn’t ask in English. Constantly she would feel like “Oh, my God, I want to go home.” However, there were brighter moments as well. In California, for example, she felt “very, very, accepted” by teachers who went out of their way to support her and spoke to her in Spanish to ensure she felt at home.

Even as she experienced many changes in her schooling life, there was one relative constant for Daniela: She told virtually no one about her status. But in high school, Daniela decided to tell a guy she liked in confidence that she was undocumented. It did not take long for the high school rumor mill to spread her secret, leading Daniela to face what she described as “the hardest thing that I experienced” up to that point.

“That really messed with my self-esteem, because I was not ready for people to put it out there,” she recalled. In addition to the usual mix of teenage insecurities, having to think about her status was particularly heavy. “I would dwell in it. I would think about it too much. It made me worry for the future, especially because around that time Trump got elected.” Despite these difficulties, she became more determined to be the first in her family to go to college.

More recently, when it came time to enter her own classroom as a first-year teacher, Daniela was eager to offer the largely immigrant student population at her school the kind of support system she had cherished. Yet the anxiety of talking about her status with students hovered over her; the thought of having to disclose her status was, to Daniela, “nerve-wracking.” But since beginning her new position, she has found that her status has become an important point of connection. “It’s somehow opened up new conversations and new relationships with some of my students,” she shares. For example, a student opened up to her about his struggles with experiencing homelessness after she shared her experiences with being undocumented. Reflecting on her own transformation, Daniela noted, “My students make me feel better about it, you know, as an undocumented teacher. . . . It’s something I was ashamed of before. And so, my students are even helping me be proud of my identity, where I come from, my struggles.”

As Daniela’s story indicates, schools have been both hostile and healing spaces for undocumented people. If schools are to be sanctuaries, we must think hard about how citizenship status continues to shape the experiences of the entire school community — including teachers. Our mixed-status research team of faculty and undergraduate students spoke with current and aspiring undocumented teachers across California, one of only a handful of states where citizenship isn’t required to obtain a teaching license. Bringing together our work in social justice education and connections to immigrant communities, we wanted to center the stories of undocumented teachers who are making vital contributions in spite of increasingly restrictive conditions. Looking more closely at their journeys into the profession can also help us understand how to confront glaring diversity gaps in the teaching pipeline. In addition to their citizenship status, undocumented teachers also discussed how being people of color, working class, queer, Muslim, disabled, English learners, and Indigenous has shaped their identities and teaching practices.

Their accounts also challenge the popular “Dreamer” narrative often invoked by politicians and the media that has turned a spotlight on high-achieving undocumented students who arrived in the United States as children and presumably stand to benefit most from immigration reform. As the story goes, these hardworking, educated young people are made to appear more deserving of sympathy and attention, often to the exclusion of other immigrant groups. A counter-narrative emerges through the voices amplified here: Aspirations and resilience cannot overcome the failures of racist and inequitable systems that serve to marginalize immigrants and undermine educators. Rafael, for instance, made clear that he didn’t want his experiences to be simply rendered into a “feel-good” story about “a Brown kid from the [San Fernando] Valley with no papers” who went on to a “fancy” graduate school and became an English teacher. He underscored what he called a “dark undertone” running through his narrative. Though typically very animated, he paused during our conversation to somberly note, “So far it sounds pretty simple, my path to being a teacher . . . but it’s always been laced with this fear of deportation and what I can do to better myself. . . . At each step I was hyper aware of what it took out of me and how much effort I had [put in].”

All teachers must contend with the question of how they show up in their classes. For many educators, it’s a matter of acknowledging how factors like race, class, ability, language, and gender have shaped their lives and how those identities carry over into the classroom. But undocumented teachers also face legal challenges that threaten their already precarious status. Sharing their stories or disclosing status are complex acts that carry political, personal, and professional implications.

Whether it’s the MAGA hat-wearing colleague down the hall or static from school administrators, several teachers also stressed the risks involved in disclosing their status at school. Melissa, a seasoned history and English teacher entering their seventh year, spoke about the pressure that teachers may feel to share their status. She explained: “I waited until I was comfortable to share. If you share your story when you haven’t processed it, it could also be really hard on your mental health. Sometimes you’re not in a school community where you would be supported if you do come out. And so I want aspiring undocumented teachers to be OK also with not sharing their story, because there are other ways that they can show up for the students and for themselves that don’t require that if they are not ready.” Sharing these stories must always be on a teacher’s own terms. They should never feel compelled to share their story or status in the pursuit of representation or inclusion.

DACA: A “Ticking Time Bomb”

Although status isn’t a barrier to obtaining a teaching credential in California, employment opportunities are severely limited. Issued as an executive order by the Obama administration in 2012, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program has been one of the only ways to obtain work authorization for qualifying immigrants. All of the teachers we spoke to are “DACA-mented” and were able to take advantage of the program in its early years. Although the program represents an important milestone in immigrant rights, it’s not without complications and currently languishes in a state of limbo. In fact, instead of seeing it as a security blanket, one teacher described DACA’s two-year renewal timeline as a “ticking time bomb.”

Amber, a preschool teacher, explained how deeply personal a seemingly administrative process can be: “My DACA got backtracked for two months and I got fired from my job, unfortunately, just last year. That was my job, I loved it. I was really happy there, that meant the world to me. I was so happy, excited because I was pursuing my dream.” At first, the waiting turned to dread. “It was hard,” Amber confided. “Every day I would wake up and check the status of my application to see if it was moved, if it was approved, but nothing. Every single day was a struggle to get out of bed.”

Although the termination was based on work eligibility, it was hard to shake the feeling that she did not belong in her school. Tired of waiting, she decided to take action. “I contacted my senator. I contacted people I knew who were lawyers. I was trying to figure it out, I just wanted answers! Because it’s not fair, it’s just awful to feel like that. To feel like, dang, I can’t work because I don’t have a work permit.” Although she was able to eventually make it back into the classroom, Amber’s concerns persist, even as it may seem to others like she has “made it” in her career. “I worry more because maybe one day they will decide, ‘Hey, [DACA] is gonna be cut out for real.’”

Even after diligently following a prescribed career path and overcoming numerous hurdles, holding a steady, public service-oriented job is not enough to safeguard undocumented teachers from potential exploitation or even criminalization. DACA-mented teachers expressed feeling stressed and worried about renewals and gaps in work authorization. Several described impending DACA renewal as foreboding, so much so that they delayed submitting their applications. Delays in the renewal process have meant gaps in employment and income, sometimes made worse by a lack of understanding or support from school administrators. When these administrative timelines cause disruptions for teachers, they ultimately impact their students as well. School districts and ally organizations can help by covering costly renewal fees and ensuring that teachers are supported given potential lapses in work authorization. Beyond that, more permanent solutions are needed. In a hopeful development with potentially wide-reaching consequences, student activists and legal scholars leading the Opportunity for All campaign in California are making the case that state entities — including school districts — can legally hire undocumented workers.

One teacher described DACA’s two-year renewal timeline as a “ticking time bomb.”

A Position of Power: Teaching for Change

Despite the issues they face with employment, many of the educators we spoke with were eager to be the teachers they never had. In addition to building community in the classroom, they reported finding ways to support their students by sponsoring student clubs, organizing legal clinics, and boosting support for English learners. Stefanie, for example, has devoted her career to supporting bilingual students at her Title I school. She herself persisted through an education system that was far less supportive of English learners. “My teaching involves creating a safe space where students are not afraid of learning a new language,” Stefanie explained. She grew especially concerned when many of her first-year English learner students would not speak to her in Spanish because they had been told not to speak it outside of their homes. Resisting a subtractive approach to schooling, Stefanie sees her approach to supporting students’ bilingualism as a way to also “encourage them to feel proud of their culture.” She has gone on to create a special program for Spanish-speaking students that the district recently adopted and expanded due to her advocacy.

Andrea, a middle school teacher, makes clear that openly discussing her status and journey was an important part of how she approached her role: “So one of my big things was that, as a teacher, I wanted to be very open or as open as I’m allowed to be about my immigration status, so that students who are in those same positions, regardless of whether they’re open about it or not, have a concrete example of somebody who is able to be part of the community and able to hold a position — in their eyes, a position of power — even though they are undocumented.”

Andrea described various ways she has wielded her power to promote safe spaces for her students. She sees her math classroom as one that welcomes students and their families, because for her, being undocumented “means that you’re also very keenly aware of who your students are, and where they come from.” In addition, she is intentional about connecting lessons with current events and has shared resources with her students to help them to become allies for BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and undocumented communities.

Even as teachers like Andrea cultivate supportive environments for their students, they must contend with educational institutions that don’t always see them. Thinking back to her credential program, Andrea appreciated culturally responsive pedagogy being discussed often in her courses. However, she found that it was up to her to drive the conversation in ways that were more inclusive of status.

“I wanted to know, right from the get-go,” she recounted, “as I’m still taking my classes, how does this impact [undocumented students]? And what tools can you give me to be better able to help them? So it was me advocating for these kids, or reminding people that this is a demographic that they’re going to encounter.”

Given that undocumented teachers are already carrying so much, the responsibility to further educate colleagues and educational leaders should not fall on their shoulders alone. Teacher educators can reflect on their approach to intersectionality and the ways they consider citizenship status when preparing new teachers. By recognizing the important roles that undocumented teachers play, we can cultivate greater solidarity across the ranks of those committed to racial and social justice in our schools.

Over-Giving: Impacts on Mental Health

Even as undocumented teachers can have profound impacts and experience joy in their work, they also confront circumstances that affect their mental health. Lupe, a social studies teacher, remembered the 2016 election and the violent xenophobia it incited. The largely immigrant student population they taught at the time was scared and anxious. Some parents began preparing their children for the possibility that they could be deported. Election day was particularly fraught as students came to Lupe to seek answers and comfort.

“I felt privileged to be able to be a teacher for students who felt so much fear,” Lupe recalled. “At the same time, I was fearful for my own well-being. I remember having the conversation with them and saying, ‘I may not be here to close the year with you.’” Had that happened now, Lupe bluntly said, “I would quit.” They added, “But I was a first-year teacher, super bright-eyed and all that good jazz. . . . I was willing to be that person for them . . . even though I wasn’t able to be that person for myself.”

When the 2020 election came around, Lupe knew “there’s no way in hell I’m gonna show up and put myself through that” again. They left town and holed up in a hotel to ride out Election Day. Lupe believes that undocumented teachers often must be especially “selfless.” Their commitment to their students can be seen as a form of cultural taxation; some teachers describe coming to school early, leaving late, and hosting students during lunch hours. After intentionally carving out space for their own mental health and self-care, Lupe advised other undocumented teachers to “just really set those boundaries, really give what you can without over-giving.” As concerns grow over the well-being of all teachers, education officials can ensure that undocumented communities have access to targeted mental health services. Moreover, we may also learn from teacher activist circles such as the Institute for Teachers of Color that are adept at providing the kind of care that minoritized teachers seldom find elsewhere.

The Struggle Continues

The vocabulary around inclusion in education circles has expanded to include a range of intersectional identities, but citizenship status often goes overlooked as a central part of what shapes our daily lives. At the same time, the space for such discussion has become increasingly unsafe. Racist policies around schools and immigration in recent years have brought about bans on both books and bodies. At the time of writing, DACA hangs on by a fraying thread. Legal challenges have halted any new applications to the program, barring a generation of future undocumented teachers from working in the classroom. Even as DACA was no doubt a hard-fought win for immigration rights, the battering it has taken reflects how flimsy and incomplete a solution it has always been. The program has begun to look more like a dead end than a lifeline. As Vanessa, a DACA-mented special education teacher, pointed out, “It sucks that even when we are somewhat privileged to have this profession, in a way, it’s still unfair and we still have to fight for every part of it.”

The voices shared here speak to how policymakers, teacher educators, state agencies, school communities, and others can better support undocumented teachers in this fight. The starting points we share here are limited to some immediate steps that allies can take. Beyond that, the pressure brought by immigration and education justice movements at state and national levels continues to be vital in combating the racism, criminalization, and legal backlash directed at undocumented communities. The classroom is a critical front in this broader struggle, as undocumented teachers lay claim not just to a profession, but the possibility for liberation. l

This article is adapted from a report from the UndocuTeacher Project (linktr.ee/undocuteacherproject). Pseudonyms have been used for all teachers in the article.